When 27-year-old Cuban American Jeanette witnesses Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials haul away the woman who lives next door, all she can think about is the child, Ana, who will come home to no mother. For a few days, caring for Ana gives Jeanette a purpose and a reason to maintain her sobriety from prescription drugs. In hearing the child’s story and seeing the ways it intersects with her own, Jeanette begins to examine the value of the lives of immigrant women in America.

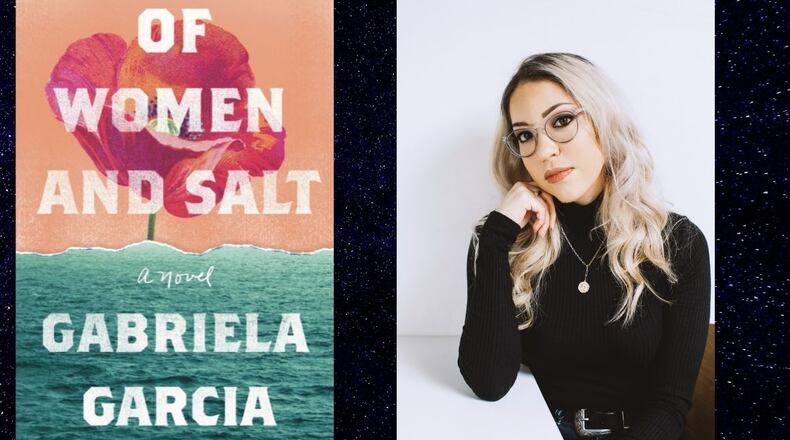

This is one of the opening scenes of Gabriela Garcia’s “Of Women and Salt.” The author covers a lot of ground ― four countries (Cuba, Mexico, El Salvador, and the United States), 150 years of history and five generations of two matrilineal families in just over 200 pages.

The novel begins with the story of María Isabel, Jeanette’s foremother, and the only woman working in a cigar rolling factory in rural Camagüey, Cuba. Set in the 1860s, during the first Cuban war for independence from Spain, the author hides the synopsis of her novel in the early parts of Maria Isabel’s story: “María Isabel thought it had always been women who wove the future out of the scraps. Always the characters, never the authors. She knew a woman could learn to resent this post, but she would instead find a hundred books to read.”

Antonio, the man she will eventually marry, reads to the laborers from the newspaper and novels to keep them entertained as they work. Like everyone else, she is bolstered by the writings of Victor Hugo. “The workers cheered when Antonio disclosed that he had in his possession a Spanish translation of yet another Victor Hugo novel, this one spanning five volumes about rebellion and redemption, political uprisings and the bonds of love, one that promised to move and enlighten before an aching conclusion.”

Garcia’s book doesn’t span the length of Hugo’s work, but all these themes, introduced early on, echo throughout the novel. The story is told from the shifting perspectives of two mother-daughter relationships: Cuban immigrant Carmen and her American-born daughter Jeanette, and Gloria and her daughter Ana, who are undocumented immigrants from El Salvador. Their paths intersect in Miami. The book captivates readers with the varied lyricism mined from each woman’s point of view, masking the author’s examination of 150 years of policy, intimidation and domination by men and by government.

At turns eloquent and exuberant, the opening voices of María Isabel and Jeanette sing, and the addition of the voices of Gloria, Ana and Carmen create a heady chorus. With Gloria gone and no way to reach her, Jeanette must decide what to do about Ana, the elementary-school aged child left behind without any relatives in America. In challenging her own mother’s ambivalent relationship toward other immigrants, Jeanette asks Carmen, “Don’t you think it’s your responsibility to give a (expletive) about other people?”

The novel doesn’t shy away from spotlighting the United States’ role in the unraveling of governments in Central and South America. The author knows how much to give the reader to make sure the forces at play are understood, but not so much that they obfuscate the story. Gloria is in detention in 2014, during the Obama administration, reminding readers that the country’s immigration policies are nothing new. The book dismantles a variety of myths, including the idea that Latino people are a monolith and function as one unified body and subsequent voter bloc — paralleling a realization apparent in the 2016 and 2020 elections.

In the end, Carmen presses Jeanette for a decision about Ana’s fate. The choice, like other decisions all these women make under great duress, propels the work forward towards an uneasy conclusion. Years of physical, sexual and substance abuse, of gang violence and political tensions mean that the attributes of self-destruction and self-determination start to look incredibly similar. The events of the novel illustrate how women grow hard, forged in a world where they have precious little control, where things are done to them and they must figure out how to recalibrate.

For all the book’s merits, there are missteps: too many other characters enter the frame. Ancillary one-off chapters from the points of view of Carmen’s mother Dolores and niece Maydelis are important to examine racism, colorism, the fantasy of contemporary Cuba and the estrangements in the story, but the inclusion of their voices does muddle things. The novel could use a better examination of what hangs in each character’s silences. Readers barely get to take a breath before the next thing ruptures the existence of these women and tests their endurance. This book, with all its traumas, tests the endurance of the reader, too.

In the end, the reader is left with a lot of unknowns. This seems to be by design and not unlike the unknowns that haunt the characters at the center of the book. For women fleeing from their current lives, it seems they can only carry what they need to remember to survive. All expendable elements of their backstories, like the names of the men who put them in precarious situations, fall away, which may leave some readers frustrated. These characters’ survival strategies relied upon silence and estrangement, and it seems to be the author’s way of signaling that not every relationship deserves to be carried.

At its core “Of Women and Salt” is about whether the world that each daughter inherits is better her mother’s. Garcia writes: “Children did not speak their minds … Children did as they were told.” After years of being stymied, across the generations each daughter answers back.

FICTION

By Gabriela Garcia

Flatiron Books

224 pages, $26.99

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured