ASO plays the long game in diversifying orchestra

When the Tri-Cities High School marching band took the field during football games in the late 2010s, Joshua Williams would step out on sousaphone, blasting out the latest songs by Bruno Mars and Beyoncé under the Friday night lights.

“It was pretty much all Black,” he says of the band that played at the East Point school, alma mater of OutKast’s Big Boi and Andre 3000.

Come Saturday mornings, Williams would be onstage in the Woodruff Center’s Symphony Hall, playing tuba in the Atlanta Symphony Youth Orchestra. It was the racial opposite of his marching band; there were very few Blacks.

That doesn’t surprise people familiar with the industry.

According to the League of American Orchestras, a recent survey of 156 orchestras in the U.S. revealed that only 2.4% of musicians are Black and 4.8% are Latino.

But efforts are underway to make those statistics more reflective of the U.S. population, which is 13.6% Black and 19% Latino.

To that end, the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra started the Talent Development Program (TDP), a musical education and mentoring program for young people of color that is unique in the nation. This year marks its 30th anniversary.

This year also marks the debut of the ASO Orchestral Fellows Program, which awards paid, two-year, part-time positions with the orchestra. It’s because of those two programs that Williams, a 23-year-old Julliard School graduate, joins the orchestra this year as a Fellow, along with Jordan Milek Johnson, a Black bass trombonist from Acworth.

“There is no world where I am where I am today without TDP. They essentially paved the road for me to have this career,” says Williams, calling from Switzerland where he is attending the Verbier Festival Academy, a prestigious and competitive training program for the best and brightest young musicians.

“They gave me opportunity and they gave me access,” he says. “In the classical music world, that is hard to come by.”

The Talent Development Program was founded in 1993 by a group of ASO supporters and volunteers headed by Azira G. Hill, wife of Atlanta civil rights leader Jesse Hill. She turns 100 in November and still attends concerts and keeps her hand in TDP.

The program selects 25 of the most promising Black and Latino musicians in metro Atlanta every year and offers them private lessons, mentorship, financial assistance, help preparing for auditions and opportunities to perform. Many participants go on to careers as professional musicians, educators or in the arts.

“TDP doesn’t just teach the instrument. It teaches you to navigate the world of classical music,” says Tara Byrdsong, a 2002 graduate of the program.

“I don’t know of any other orchestra with a similar program, at least not in the same way or as well known,” says Andre Dowell, chief of artistic engagement for the Sphinx Organization, the leading national organization promoting diversity in classical music.

Weston Sprott, dean and director of the Preparatory Division at The Juilliard School, agrees.

“To most Black musicians, the statistics come as no surprise. Even in the last couple of years, post-George Floyd, there has been a lot of conversation about wanting to do better, but there hasn’t been a lot of actual substantive change,” says Sprott, a founding member of the advocacy group Black Orchestral Network (BON).

Last year, BON circulated an open letter to American orchestras that said, in part: “As Black musicians within this community, we have too often experienced significant barriers to inclusion, inequities in treatment and process, and indignities and devaluing of our musicianship and talents.”

According to the Human Resources Department of the Woodruff Arts Center, 8% of the musicians that make up the orchestra are Black or Latino.

“We’re trying to do everything we can within our industry to provide access and do our part in terms of some of these inequities,” says Brandi Hoyos, ASO director of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The pipeline from being a young Black classical prodigy to a full-time seat in a symphony orchestra is narrow and difficult, but TDP graduates pursue many paths. TDP alum Tara Byrdsong is currently the director of bands at Campbell Middle School in Smyrna and a former member of the Cobb Wind Symphony.

“In elementary school the band was rehearsing in the cafeteria; I could hear them, but I couldn’t see them. But I knew I wanted to do whatever that was,” she says.

She was selected three times to attend the prestigious Brevard Music Center Summer Festival in North Carolina while she was a student at the majority black Cedar Grove High School in south DeKalb County.

“The first summer I went to Brevard it was a culture shock after Cedar Grove,” she recalls. “Everyone was white or Asian. And I felt like I was out of my element.

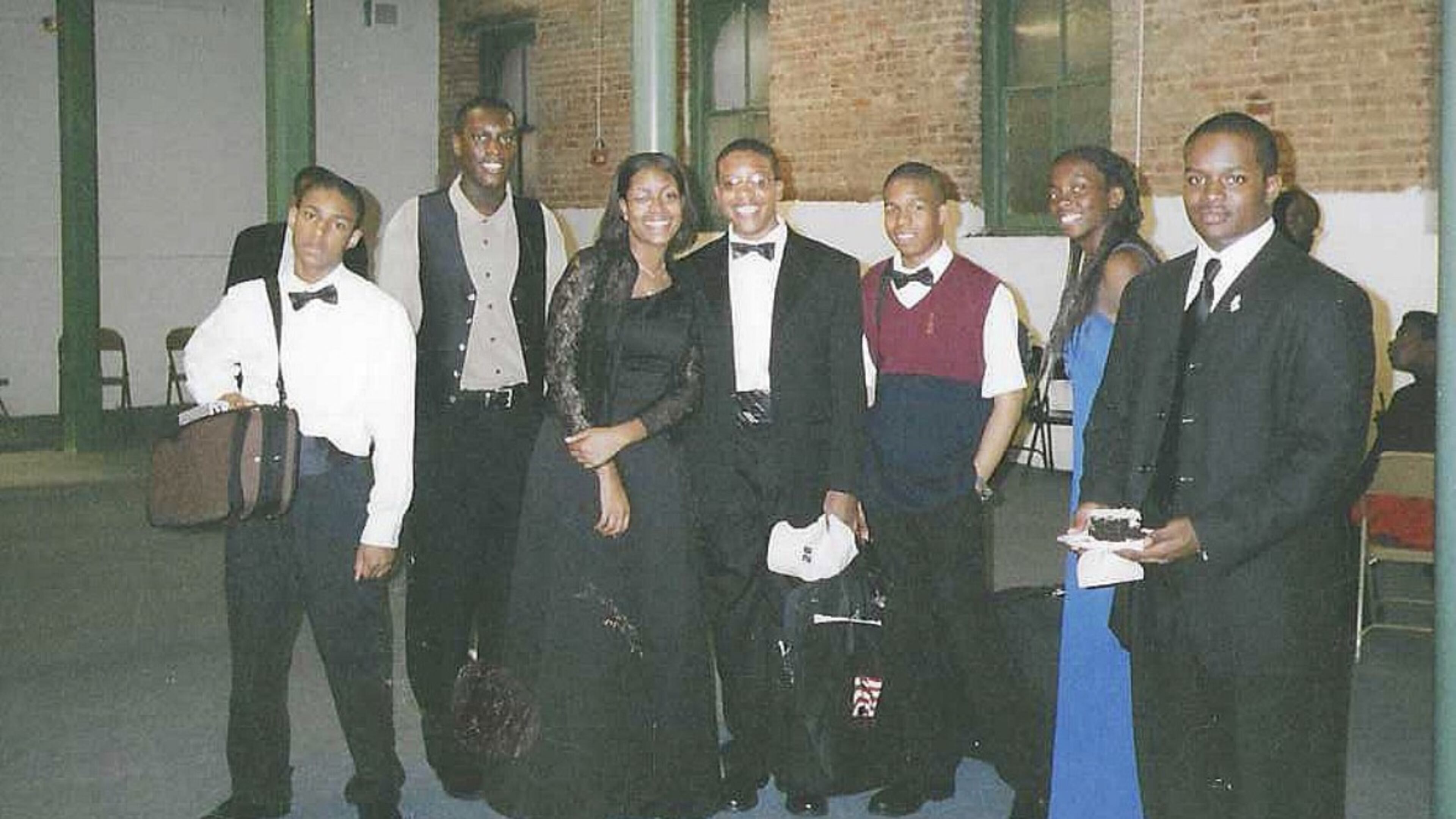

“I’m very appreciative of my time in the Talent Development Program,” she continues. “It was fun to be around students who were like-minded and who looked like me.”

Black Orchestral Network and The Sphinx Organization maintain that long-standing practices in most major orchestras, especially lifetime tenure for musicians and some audition processes, work against Black musicians who seek full-time employment. They are advocating that orchestras change some of those structures, but union contracts can make that difficult.

The ASO has tried to address those issues with its Orchestral Fellows Program.

“The ASO is committed to helping change the future face of the American orchestra,” says ASO Executive Director Jennifer Barlament. “We view this program as the logical extension of our existing programs that are dedicated to supporting a diverse infrastructure of musicians here in Atlanta.”

When Williams and his tuba return to Atlanta from Switzerland in August, he will start preparing to play with the ASO in the fall. He describes the Fellow position as “a bridge between school and a full-time position.”

Because there is only one tuba in an orchestra, he and ASO principal tubist Michael Moore (who was his TDP instructor) “will likely rotate weeks and split concerts,” says Williams. “I don’t know exactly how things will work.”

But Williams knows that because Moore is the ASO principal tuba player and has tenure, there really is no path for Williams to join the ASO full time. He will have to audition for scarce spots in other orchestras.

“I haven’t experienced a ton of discrimination at this point in my life,” he says. “I went to Julliard, which is one of the most liberal institutions in the country.

“But as I’m about to enter the professional world,” he continues, “I am bracing myself for anything that could happen. I don’t think anything could surprise me.”