50 years ago, Atlanta’s gay rights push took to street for first time

The group inched its way up Peachtree Street to a soundtrack of chants, kazoos and a tambourine.

Mindful that stepping off the sidewalks could get them arrested — the city of Atlanta had turned down their request for a permit and the police were closely watching for jay-walkers — the marchers stopped at every corner until they were given the crossing signal.

Atlanta’s first gay pride march, on the bright Sunday afternoon of June 27, 1971, was virtually unrecognizable from the 300,000-person, multi-day celebration it has become in recent years.

When the Georgia Gay Liberation Front organized that first demonstration 50 years ago, there were no floats or cheering spectators, no major corporate sponsors or caravans of pandering politicians.

Even in the city that had just birthed the civil rights movement, LGBTQ rights was considered a radical issue that the political establishment, including many Atlanta progressives, wanted to stay away from. At that time, gay sex was still illegal under state law, and the American Psychiatric Association characterized homosexuality as a mental illness.

It would take decades for attitudes and laws to change. Even today, six years after the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage, Congress, statehouses and the courts continue to grapple with LGBTQ protections, “religious freedom” and transgender youths.

But for the hundred or so Atlantans who participated in the city’s first pride march, the event was a turning point, a moment when, for the first time, they could publicly celebrate a part of themselves that society had long demanded they keep hidden.

“It was mostly about feeling good,” said Phil Lambert, a Vietnam veteran who was in attendance. “That we’re not a bunch of sick people. That we’re not the problem.”

Raids and stings

For many local activists the match was lit nearly two years earlier, on Aug. 5, 1969.

It was six weeks after cops had raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay hangout in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, galvanizing the fight for LGBTQ liberation. Nearly 900 miles away, some 70 moviegoers had settled into their seats at the Ansley Mall Mini Cinema in Midtown for a Tuesday evening showing of Andy Warhol’s “Lonesome Cowboys.” The western satire, which featured gay sex scenes, had become an immediate target of local law enforcement who believed it violated obscenity laws.

Roughly 15 minutes into the film, the lights flipped as police burst into the theater and locked the doors behind them. Officers arrested the manager and projectionist for pornography, confiscated the film reel and lined up members of the audience.

“They had cameras with flashbulbs and they were taking everyone’s picture,” Abby Drue, an Atlanta nonprofit chief who was in the theater, recounted during a recent interview. “They were arresting a lot of gay men, just arresting them on anything they could find.”

The goal of the raid, Fulton’s solicitor general later told the Atlanta Constitution, was to identify anyone with “records for previous sex offenses.” But for many the true intent was obvious.

Law enforcement had long targeted the city’s LGBTQ population, particularly gay men, in hangout spots like Piedmont Park and along what was known as “the strip” on Peachtree Street. In 1953, police used a two-way mirror before arresting 20 men for having sex in the basement toilets of one of Atlanta’s public libraries.

At that time, many gay Atlantans were closeted, even entering heterosexual marriages, fearful they could lose their jobs and be shunned by their families if they were found out. Some were able to live a little more openly, and Atlanta became a magnet for young LGTBQ people from small towns all over the South.

By the 1960s, a handful of bars began springing up near Midtown that quietly catered to gay clientele. “It was a secret world,” said Gil Robison, an LGBTQ activist who grew up near Tucker. “It was like another world that was laid on top of the world that everybody else sees.”

Lesbians lived in a world with a different set of rules, which often included the crushing social pressure to marry young, have children and follow the South’s traditional gender roles.

“There were women who really had to live a double life,” said Drue, a lesbian. “People couldn’t be relaxed.”

Fed up

After the Ansley raid, a group of fed-up activists huddled at New Morning Cafe near Emory University and launched the Georgia chapter of the Gay Liberation Front.

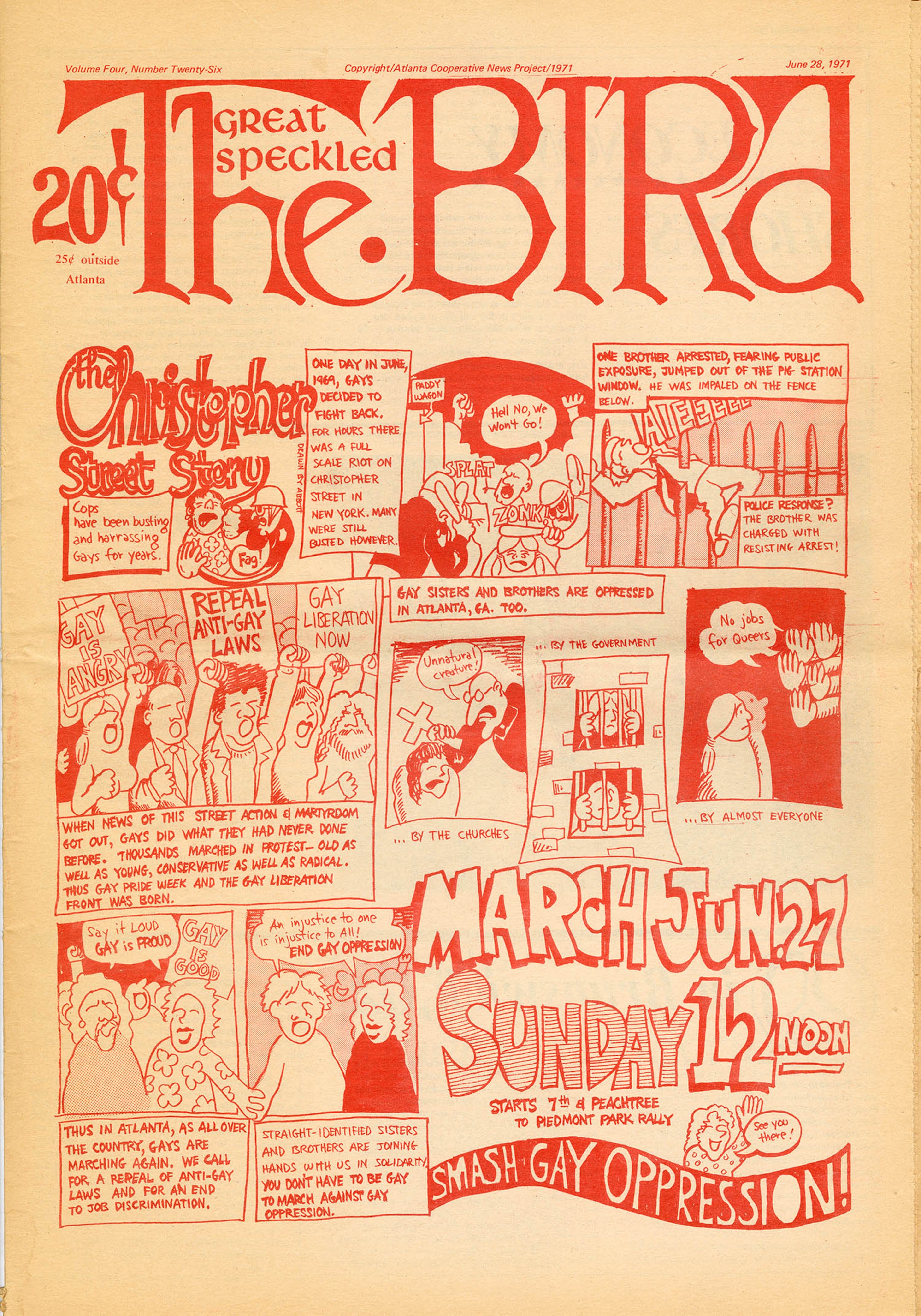

Among members, who were young and mostly white, many had cut their teeth on the other social movements of the 1960s, including women’s liberation, anti-war and civil rights fights. Some identified with socialism or Marxism and others were hippies and counter-culture types who’d been inspired by coverage in underground newspapers like The Great Speckled Bird.

Activists focused not on marriage but the repeal of sodomy laws and protections from discrimination. (Until 2020, when the Supreme Court ruled on a case involving a Doraville man, it was legal for an employer to fire a worker because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.)

The organization set up a table at the Piedmont Park Arts Festival to mark the first anniversary of Stonewall in June 1970, but shied away from holding a full-scale march. By the following year, the GLF was ready for its first public show of force.

That spring, the city of Atlanta had turned down the group’s request for a permit to march in the street. The GLF appealed to the ACLU for help but they were turned down because “we weren’t a minority,” Berl Boykin, one of the late leaders of the GLF, said during an oral history interview with Georgia State University in 2017. (Andrea Young, the current executive director of the ACLU of Georgia, said that, “while I have no information on that recollection, what I can say is that the ACLU of Georgia challenged Georgia’s sodomy law in the 198Os and continues to be a fierce champion of LGBTQ+ rights.”)

Despite the hiccup, organizers decided to move forward with the event.

That late June afternoon, an estimated 125 marchers assembled at the corner of 7th and Peachtree. The group unfurled a lavender “gay power” banner and began chanting “out of the closet, into the streets.” As they walked, some handed leaflets to stunned churchgoers who had never seen a gay pride march before.

Leading the procession was GLF leader Bill Smith, who embodied the decade’s disco glamour that day with a massive Barrymore collar, long sideburns, thick-rimmed aviator eyeglasses and a white handbag.

“We hope through this march people will realize that homosexuals are good, law-abiding citizens, that we do have responsible jobs and positions,” Smith told a reporter from WSB-TV. “As such, we do not feel that laws that are repressive to us should be on the books.”

The crowd made its way to Piedmont Park, where participants put on skits. In one, the cops shouted epithets at a gay couple, only to be drowned out by chants of “gay is proud.” In another, a panel of experts on the “Slick Cavett Show” cross-examined a straight couple: “How long have you been this way?”

AJC coverage

Media coverage that day was thin. The Atlanta Journal didn’t send a reporter to the march — it instead published eight paragraphs from United Press International, a story that noted that 50 “self-proclaimed homosexuals” took part.

The Journal and the Constitution rarely covered the gay community at that time, and when they did, LGBTQ readers often found the tone reductive or downright offensive.

In 1975, the Constitution ran a three-part series on “the lifestyles of Atlanta homosexuals” that heavily quoted a sex crimes detective who said murders involving LGBTQ people were among the city’s most violent slayings.

“Gay people insist that the homosexual community actually is very much a mirror of heterosexual society, that, like the heterosexual community, they have their perverts and sickies and weirdos, but no more than their share,” the story stated. “In fact, Atlanta’s gay community does seem to have infinite variety. There are drag queens and swishy, effeminate men. There are the leather jacketed, coat-and-tie, butch-haired, ‘dyke’ women. There are the ‘glitter set’ men, all styles and show and masculine prettiness, who lean toward bisexuality.”

In response, LGBTQ leaders blasted the paper for “employing the more irascible stereotypes in the community.”

That wasn’t the only time the Journal and the Constitution drew ire for their treatment of LGBTQ people. In 1973, according to local LGBTQ historian Dave Hayward and others, the Journal fired Charlie St. John, a copyboy and member of the GLF, for putting flyers into newsroom mailboxes advertising the pride parade. (An AJC HR representative said the paper no longer possesses employment records from before 2000 and could not confirm the circumstances.) That year, St. John became the city’s first gay appointee when Mayor Sam Massell tapped him for the city’s Community Relations Commission.

Growing clout

As the 1970s rolled on, the city’s pride marches grew larger and larger. But it would take a few years for politicians to begin recognizing the clout of the gay community.

A turning point, according to Hayward, came in 1976, when Mayor Maynard Jackson proclaimed June 26 as “Gay Pride Day” in Atlanta, a move that prompted blowback from religious conservatives, including calls for his resignation. The next year he dubbed the same day “Human Rights Day.”

By then, GLF had splintered. Less-political members had drifted away. Lesbian advocates, some of whom had felt sidelined, had started their own groups like the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance.

Members “wanted to have someplace where they felt empowered and didn’t have to deal with any kind of nonsense, even from men who were brothers in the struggle,” said Lorraine Fontana, a founding member of ALFA.

One group that was not as well represented in the GLF or early marches was LGBTQ people of color, some of whom had felt shut out of some white social circles both formally and informally. Several of the city’s most popular gay bars, for example, were notorious for discriminatory policies that required Black patrons and women to provide multiple forms of ID to order a drink.

“We were often I think marginalized and left out from some of the institution building that some of the white LGBTQ folks were doing in Atlanta,” said Charles Stephens, executive director of the Counter Narrative Project, an Atlanta nonprofit that seeks to elevate the voices of Black gay men. “But I also think there were some Black gay men who wanted to build their own institutions.”

The city’s westside became a thriving center for Black LGBTQ social life around the same time, with the opening of bars like the Marquette and parties in the homes of prominent gay Atlantans such as the late physician and art collector Otis Thrash Hammonds, according to Stephens. Others did get involved in more integrated activist circles.

Decades later, a network of Black gay men built what would become Atlanta Black Pride, an annual event that started as a picnic among friends in 1996 and has grown into a 10,000-person festival each Labor Day weekend.

Today, the city’s largest LGBTQ event is the festival that descended from the 1971 march. Atlanta Pride attracts hundreds of thousands of people, including the mayor and almost every major Democratic politician. It spans several days in October — organizers moved it to the weekend of National Coming Out Day in 2010 after a drought caused the city to limit summer permits for Piedmont Park — and includes a parade, educational events, drag shows and vendor market.

In one of the biggest shifts from 50 years ago, the same police force that once harassed and arrested many Georgians for being gay now re-routes traffic and provides security for the parade, with some uniformed officers marching alongside revelers.