Captivating ‘Cool Town’ chronicles history of Athens’ music scene

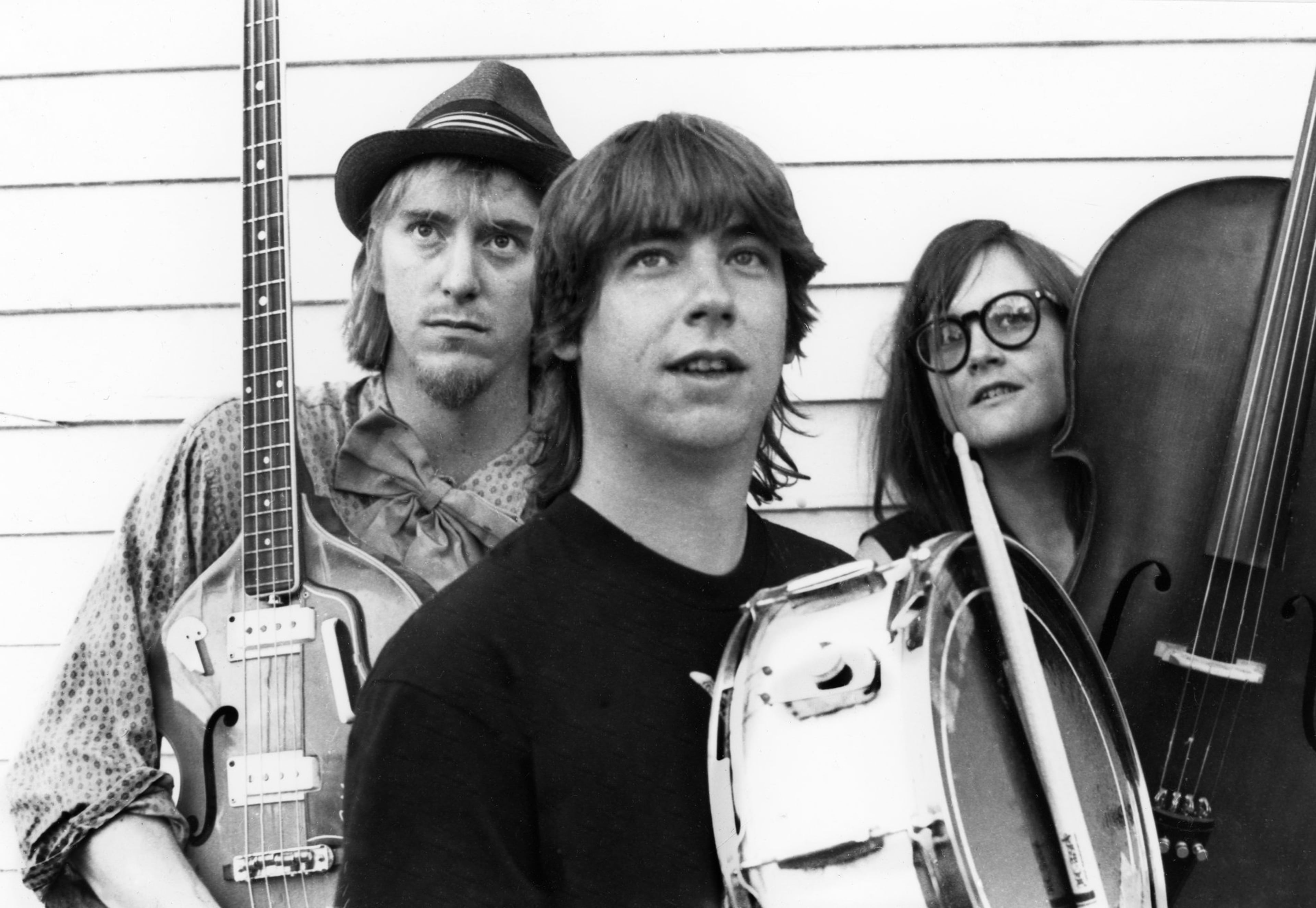

In 1982, Grace Elizabeth Hale arrived at her freshman dorm at the University of Georgia with a sailor dress and an add-a-bead necklace, and promptly went out for sorority rush. Five years later, she was entrenched in the local music scene as a member of the trio Cordy Lon and as co-owner of the Downstairs, a small restaurant and music venue in the heart of town. Her evolution from sorority hopeful to alt-music insider played out against the culture-shifting transformation of Athens from a small, isolated university town to the epicenter of indie music in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

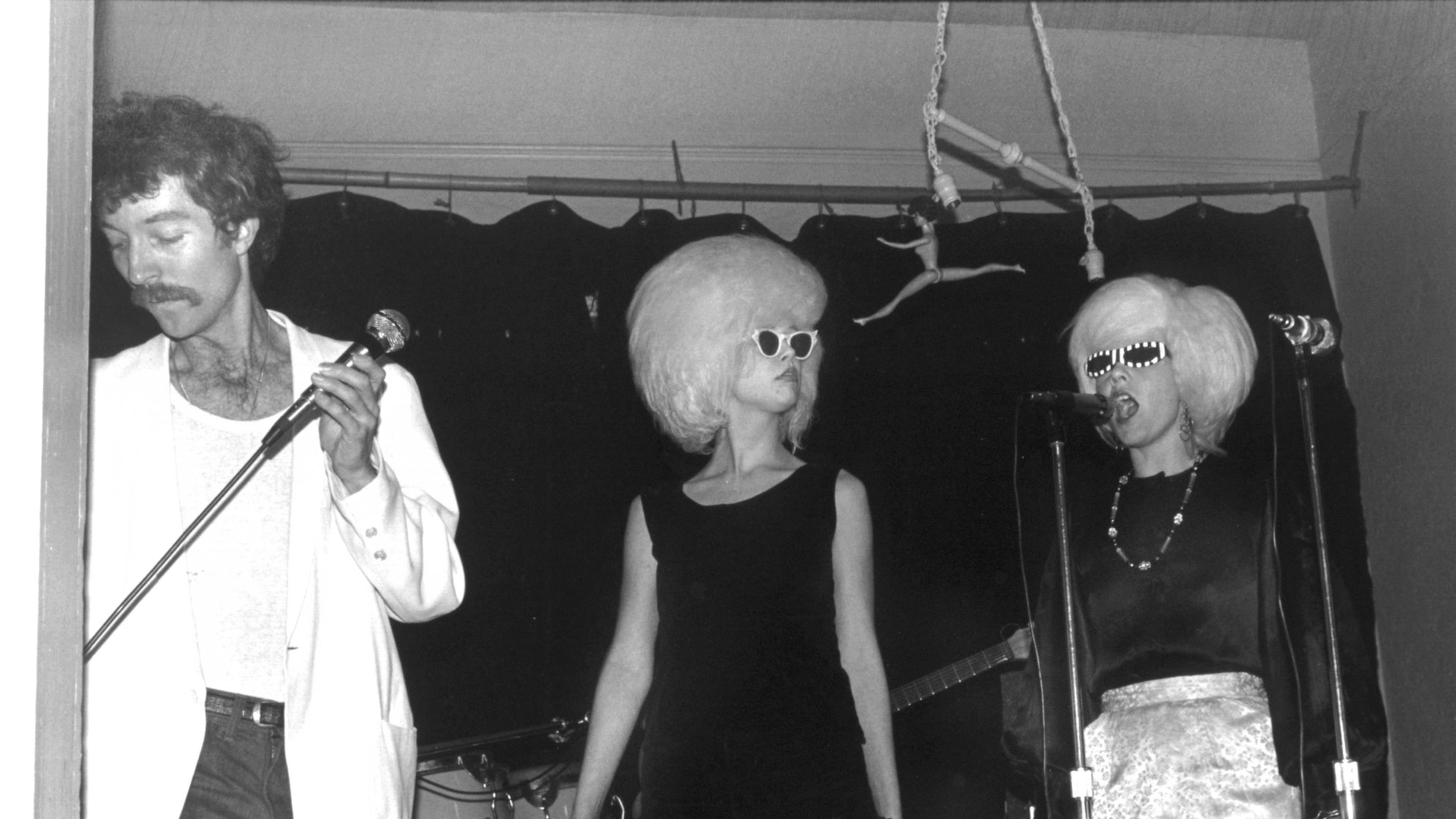

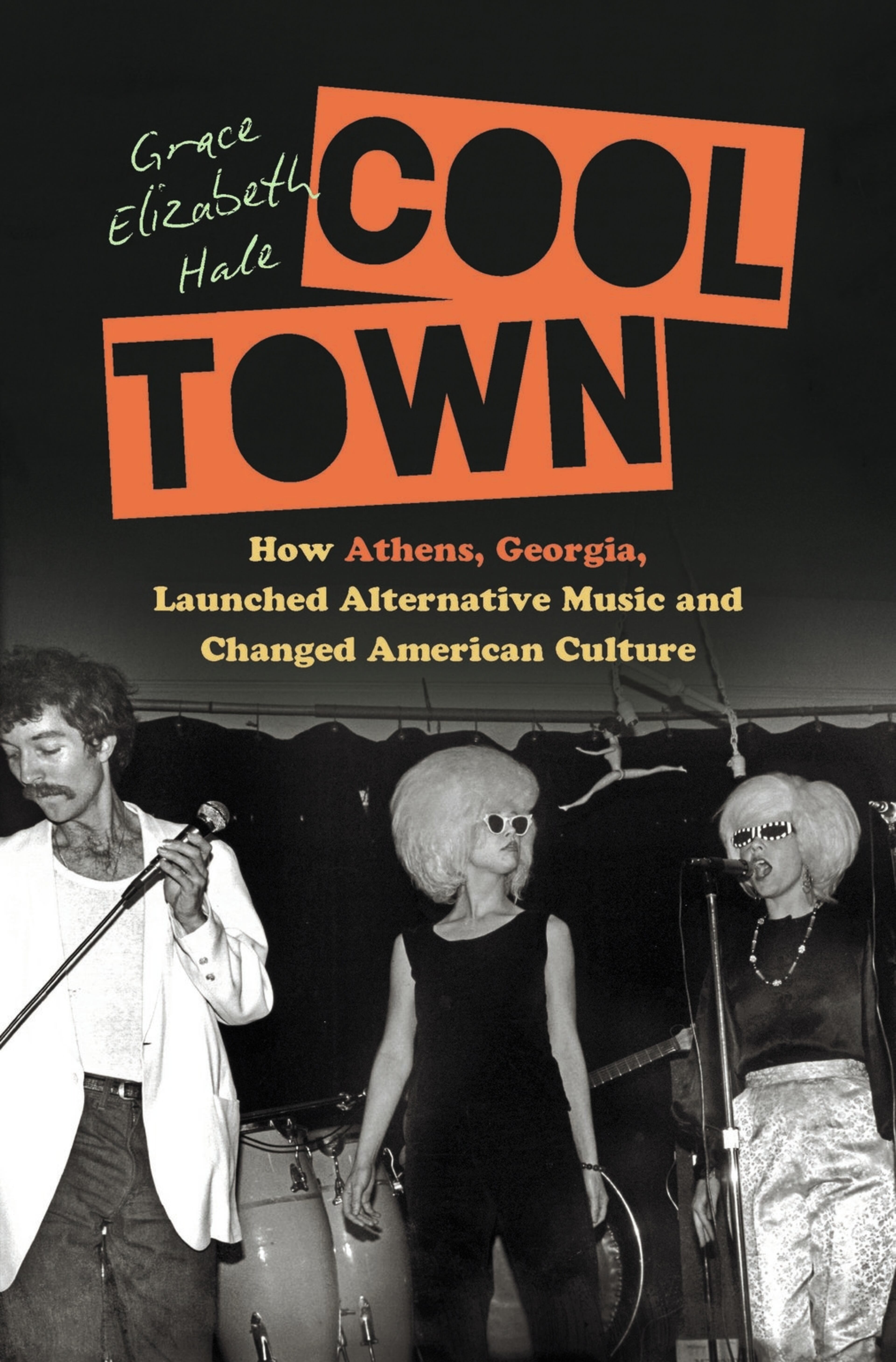

Today Hale is a professor of American studies and history at the University of Virginia, and she has written a deeply researched, highly engaging history of the Athens music scene. "Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia, Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture" (University of North Carolina Press, $27) chronicles the birth of the scene at a Valentine's Day party in 1977 when the B-52s debuted, and follows the rise of Pylon and R.E.M., as well as the contributions of many other musicians, artists, personalities, venues and media outlets that helped alter the course of pop culture.

Hale, who will appear at the Highland Inn Ballroom in Atlanta on April 7, recently spoke to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution about "Cool Town."

Q: What made Athens such fertile ground for the birth of the alternative music scene?

A: The standard answer that participants gave in the early years is: cheap rents, the presence of the university and small-town boredom — we had to make our own fun. All of those are really important things … but I don't think that explains it. A part of the piece that is often left out of the story is the presence of a robust and not completely closeted gay community in Athens. It was that community and the presence of a few key individuals who had this kind of experience of bohemian alternative experimentation outside of Athens — most particularly that would be Jerry Ayers, later known as Jeremy Ayers, who spends time in New York City with the Warhol Factory scene during the period when Warhol was connected with drag queens and his whole superstars projects and all of that. Jerry is friends with Ricky Wilson and Keith Strickland, who, of course, founded with their friends the B-52s. They go up to visit Ayers in New York City and hang out with the drag queens at the Factory. This is a pretty incredible experience for young men who, I think, they're still in high school. So that glimpse of another world … gives them an idea of what's possible.

Q: Part of the lore of the Athens music scene is the fact that many of these bands, including the B-52s and Pylon, had barely touched an instrument before they started writing songs and putting on shows. What contributed to this idea that audiences would be receptive to such a raw sound?

A: It comes from two places. The standard story of popular music is it comes from punk. You know, learn three chords and you can start a band and that produces the whole high school garage rock phenomenon. There are lots of underground bands in New York in the mid-to-late '70s, bands that are sort of willfully playing around with how they can, quote unquote, be bad like the Ramones. I think that's one strand. But I think another really powerful strand is the art school in Athens at that time is really dominated by …. this kind of anti-craft vision of art. They were very much influenced by experimental teaching methods that suggested anyone can learn to draw, anyone can learn to be an artist. What matters is putting your feelings into it. This is now de rigueur in art schools, but it was new at the time — that people would work across mediums. That someone specializing in sculpture would make photographs. And that was very much the spirit of the art school in Athens. You just have to be daring enough to try it. Musical instruments were just another tool like picking up a camera if you weren't trained as a photographer.

Q: Part of the appeal of the music coming out of Athens in the ‘80s is it made dancing cool again, which is something that distinguished it from Southern rock, right?

A: It distinguished it from Southern rock, and it distinguished it from a huge amount of music coming out of the New York City underground at the time. The post-punk world was getting ever more serious. In what is called in New York City the No Wave scene, nobody is smiling, everyone is grim, everybody's staring at the floor and strumming dissonant chords. And these Athens kids are jumping around like silly and crazy and goofy. It's different. It sticks out.

Q: You portray R.E.M. as outliers on the scene in a lot of ways. They were criticized for being too pop and for attracting the frat crowd to venues like Tyrone’s. Can you talk about that?

A: It's a story that scene insiders obviously know. They are seen as too poppy and part of that is because when they emerged, they're like: Nobody is playing this kind of garage rock sound, so we're going to do that. There was this thing in Athens where everyone was trying to stake out different sonic territory. If you think about it, the B-52s don't sound like Pylon; they don't sound like the Method Actors; and they don't sound like Love Tractor.

But it may be a story that is a little over-exaggerated. There are a few key people who see themselves as bohemian gatekeepers and they’re critical. But it definitely has real effects. In some ways, it makes it really beautiful how much R.E.M. supported Athens and were invested in the town. They were really invested in the local scene, producing recordings for other musicians, going out to see people play. Even when they were out there on tour, they were creating a network all over the country. There’s so much written by other musicians and bands from other places about how R.E.M. would introduce them to their fans in other towns and they would be swept up in this R.E.M. network and people would put them up and take care of them. To me, that made the story more beautiful because they weren’t replicating the way in which other people were snobby to them.

Q: How did R.E.M.’s success affect the Athens music scene?

A: Their success does spur people — in many ways more outside of Athens than inside Athens — (to create) mini R.E.M.s all over the place. It creates more professionalism in the scene and less space for amateurism. People are very hush-hush about their ambition, and people who aren't hush-hush about their ambition and openly speak about it, they end up getting shunned by certain people. More bands are thinking of (music as) a long-term career. People are beginning to consult with entertainment lawyers and more professional management companies and booking companies. There is a rise of four white guys in a band. But it's also interesting how immediately that creates a backlash. There were just as many people trying to be the next R.E.M. as there were those trying to be the opposite of that.

Q: You interviewed more than 80 people for your book, including members of the B-52s and Pylon but no one from R.E.M. I assume you asked and they declined?

A: Bertis Downs, their longtime manager and lawyer, was a neighbor of mine for many years, and I interviewed him and talked to him. He passed along my request, but they didn't want to be interviewed. It's been a long time that they've had a policy of not talking to anybody. To be completely fair to them, if they want to say something about their thoughts about Athens and their music, they can say it to the world. I didn't take it personally.

I will say that the upside of that was I was free to interpret their history without having their contemporary voice in it. What I did was I tried to track down every single article about them, every interview with them that was produced over decades, and even radio interviews. I really tried to listen to it all chronologically in a short period of time. That gave me an interesting sense of how they changed how they thought about their image and their own history over time, as we all do, right? When you digest all that in one chunk, you get this interesting sense of how they’re creating their image in various moments and how that is changing over time. It was great to be able to try to convey that and convey how deeply rooted in Athens they are, how much Athens nurtured them, and how much they have nurtured Athens — but that it hasn’t always been an easy, rosy, perfect relationship.

Q: One of the greatest talents but also one of the greatest tragedies on the Athens music scene was Vic Chesnutt (who died from a drug overdose at age 45 on Christmas Day 2009). How did he influence the scene?

A: He (gave) storytelling a kind of artistic cachet it didn't have before. Storytelling hadn't really been a part of the Athens scene until Vic Chesnutt. There was attention to language in interesting ways in other people's lyrics and interest in the literary version of dissonance in words that clashed together or sounded unusual or bizarre. That kind of interest in words was there in Pylon, in R.E.M. But that's not storytelling. Vic really in some ways seemed retro, but his storytelling was (about) what it was like to be a part of an alternative music scene and live this kind of attempt at being anti-racist and anti-homophobic and how people don't succeed at that, and how they bring their baggage, at least in the case of Athens, from their Southern childhoods into it. He was examining all of these things in his music and telling stories about ambiguity and very modern tensions around identity and sexuality that were anything but retro. It was really profound. Nobody did that like Vic.

Q: In reference to the subtitle of your book — in a nutshell, how did Athens change American culture?

A: I will say that the trend in the titles of books that publishers hope to sell is to overstate the argument, so it's a little bit of that trend. But at the same time, I do think that one of the key ways in which (Athens shaped) American culture is by creating a kind of vision that you can make this creative, interesting life. You can create your own culture, as opposed to some kind of corporate-dominated mass culture. You can create alternative culture wherever you are.

Questions and answers were edited for clarity and length.

AUTHOR EVENT

Grace Elizabeth Hale. Author of "Cool Town" in conversation with Tony Paris, managing editor of Creative Loafing. 7 p.m. April 7. Free. Highland Inn Ballroom, 644 N. Highland Ave., Atlanta. Presented by A Cappella Books. 404-681-5128, acappellabooks.com.