Fostering empathy through immigrant stories topic of book fest keynote

The U.S.-Mexican border is a symbol of life, death, escape, unity and disunity in literature and in our nation’s polarizing debate over immigration today.

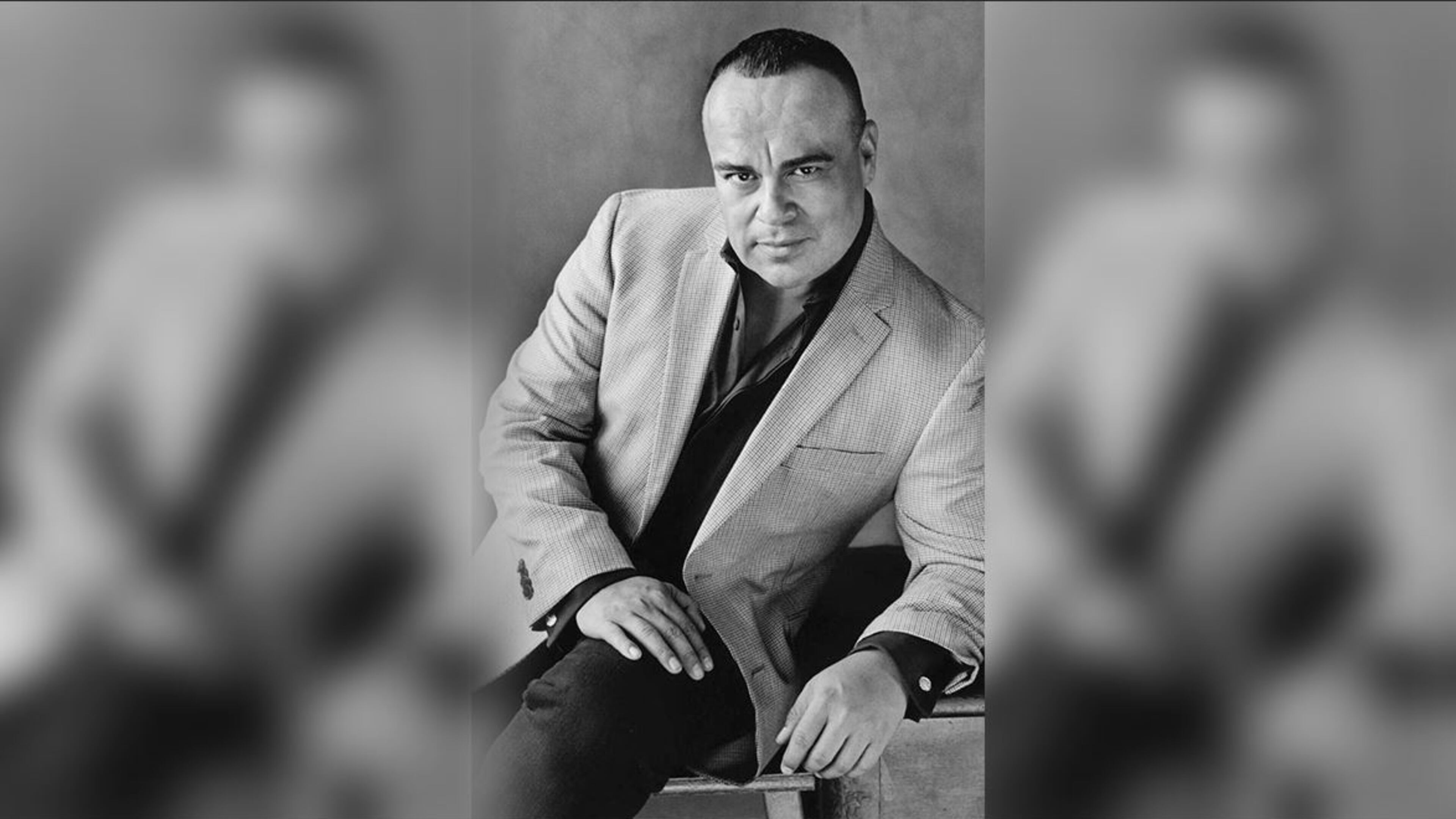

Writers Rigoberto González, Richard Blanco and Gabriela Baeza Ventura repeatedly dive into those themes, while humanizing the people on both sides of the Rio Grande. Paraphrasing the late Chicana writer Gloria Anzaldúa, González calls the border a wound between the third- and first-worlds.

“The border represents not only a connection but also a collision,” said González, 49, an acclaimed poet and memoirist who teaches creative writing at Rutgers University-Newark. “It is a bridge, but it is also a wall. It is a very complicated symbol.”

González will join Blanco and Ventura in discussing these themes at the AJC Decatur Book Festival's keynote event Aug. 30 at 8 p.m. at Emory University's Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts. Called "Effecting Change in a Changing World: Latinx Writers on Immigration," the event will be moderated by Univision Atlanta's Mariela Romero, kicking off a track of author appearances curated by the festival and PEN America and devoted to the issue of immigration.

The topic is a deeply personal one for González. He was born in Bakersfield, California, to Mexican grape pickers who lacked legal papers. The family moved back and forth across the southwest border, struggling with poverty and hunger. González learned English and became his family’s translator, eventually leaving for college and publishing 17 books of poetry and prose. Now when he returns to his homeland of Michoacán to visit his grandparents in Mexico, he arrives unannounced and stays for just a day because of the threat of violent crime there. He doesn’t want relatives to be kidnapped by criminals who might mistakenly believe he can pay a huge ransom.

González’s most recent poetry collection, “The Book of Ruin,” which he describes as an “apocalyptic narrative,” squarely addresses the divisive issue. In “El Coyote and the Furies on the Day of the Dead,” he writes about how human smugglers operating along the southwest border forsake their charges:

You can’t belie / this truth: you help them die — / the promises you make are lies, / coyote. They wait, you don’t arrive.

González wants the keynote discussion at Emory to help portray Hispanics in a more comprehensive way.

“Our experiences have been amplified through a very negative lens, from the ICE immigration raids to the mass shooter in El Paso, Texas. One way we make headlines is through our tragedies,” he said. “I am hoping that this conversation is going to remind people that we are more than the tragedies, we are more than the headlines — that we are also writers. We are also professors. We are also artists who contribute to the cultural fabric of this nation.”

His fellow panelist, Ventura, 49, teaches Gonzalez's and Blanco's writing at the University of Houston and supervises the production of more than 30 titles each year for Arte Pύblico Press, the nation's largest publisher of U.S. Hispanic authors. This year, the National Book Critics Circle named the publisher the recipient of the Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement Award for its contributions to book culture.

In 1992, the nonprofit press started the Recovering the U.S. Hispanic Literary Heritage project, which publishes lost Latino writings. It is an effort that, Ventura said, “is especially crucial now given all the negative rhetoric surrounding Hispanics in the United States.

“Because it is a book festival I want to reinforce the fact that Latinos have been writing and creating literature from the colonial period before this country was named the United States,” said Ventura, a naturalized U.S. citizen who immigrated from Ciudad Juárez to El Paso when she was a girl. “I hope that conversation will lead us to that, to really showcase and really bring light to the work that U.S. Latino writers are doing.”

Arte Pύblico Press is the original publisher of Sandra Cisneros’s “The House on Mango Street,” the sweet and heartbreaking story about a Mexican-American girl who grows up in a large family in Chicago while dreaming of having her own home. The work is still relevant today, Ventura said, because it “teaches us that the world needs to adjust to who we are. We need to claim our names. We need to claim our space. We need to claim our identity. We need to build our own houses, whatever that may look like.”

Blanco, 51, made history when read his poem, "One Today," about a nation of diverse people at President Barack Obama's 2013 swearing-in ceremony. He became the youngest, first Hispanic, first immigrant and first openly gay man to read at a U.S. president's inauguration. Later that same year he read the poem at the AJC Decatur Book Festival.

Born in Spain to Cuban exile parents and raised in Miami, Blanco often writes about cultural identity. His latest collection, “How to Love a Country,” explores the same themes, reflecting on President Donald Trump’s proposed expansion of the southwest border wall, Blanco’s father’s efforts to learn English and the plight of Dreamers, young immigrants who were illegally brought here as children.

In “Complaint of the Río Grande,” he personifies a river that sometimes swallows desperate immigrants fleeing violence and poverty:

I wasn’t meant to drown children, hear / mothers’ cries, never meant to be your / geography: a line, a border, a murderer.

While Blanco details America's divisions in his work, he maintains a hopeful tone and stresses the importance of unity. In "Election Year," he writes about garden flowers that "thrive in shared soil, drink from the same rainfall, governed by one sun." In "Declaration of Inter-Dependence," he intersperses lines from the Declaration of Independence with his poetry, concluding: "We're the promise of one people, one breath declaring to one another: I see you. I need you. I am you."

Among the topics the keynote address is expected to tackle is the power of literature to bring about change. Poets and writers, Blanco said, are “emotional reporters” who tell stories that “humanize and bring to life some of these political issues that can get very abstract very quickly.

“I am not as naïve to think that a poem can change the world,” Blanco said, “but I do still believe that poetry can change one person at a time, and if that person is changed then that person can affect many things in the world.”

AJC Decatur Book Festival. Aug. 30-Sept. 1. "Effecting Change in a Changing World: Latinx Writers on Immigration" keynote event. 8 p.m. Friday, Aug. 30. Free, ticket required. Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts, 1700 N. Decatur Road, Atlanta. www.decaturbookfestival.com