Restored Cyclorama opens

The colossal “The Battle of Atlanta” painting, which once toured city to city like a rock musician, has seen hard times.

It’s been torn, stained, ripped, abandoned and left out in the weather.

Crudely nailed into circular showrooms in cities such as Minneapolis, Indianapolis and Chattanooga, it’s been chopped back down again when it was time to move to the next town, leaving strips of Belgian linen behind.

Whole vertical sections have been lopped off. Soldiers have been painted in and out.

After it came to rest in Atlanta in 1892, the 358-foot-long, 42-foot-high cycloramic painting spent a lifetime in a leaky exhibit hall at the edge of a zoo. Owned by the city of Atlanta, the mammoth work of art was deteriorating and wasn’t getting much attention. It seemed a sort of afterthought, a curiosity, within smelling distance of the elephant house.

Then came a cascade of changes.

In 2008 “The Battle of Gettysburg,” the only other cycloramic painting on display in this country, received a dramatic restoration. It was not only stunning, for some viewers it induced vertigo. Atlanta leaders visited, and saw the potential that the “Atlanta” might have.

A Buckhead businessman, reading about the trials of the Atlanta painting, offered $10 million in seed money to build a new structure to house the painting. In July 2014, the city, considering three different locales for the painting, signed a 75-year agreement with the Atlanta History Center.

After three and a half years of work and $35.8 million, the newly restored “The Battle of Atlanta” will open its doors to visitors Feb. 22 at the brand-new Lloyd and Mary Ann Whitaker Cyclorama Building, a 25,000-square-foot rotunda on the History Center campus.

“We are excited and thrilled,” said Whitaker, 85, whose company specializes in disposing of ailing businesses. “We never envisioned that it could look this good in that wonderful building.”

> RELATED: From 1886 to now, a timeline and history of Atlanta's Cyclorama

Mutable symbol

It’s a tricky time to enshrine this historic object, a time when conflict over Civil War memory can erupt into vandalism and violence. The deadly riot in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the toppling of the “Silent Sam” statue in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, demonstrate how the issue can become heated.

> RELATED: Atlanta debates the future of its Confederate monuments

History Center President and CEO Sheffield Hale said the changeable symbolism of the Cyclorama is representative of the changing times. It vividly portrays a pivotal moment in the creation of the city of Atlanta, but it is also a lesson in how we read history, how the same story can mean different things to different audiences.

“I think the painting is one of the most important artifacts in the country for a number of reasons,” he said. “From a scarcity value: There are only two. But more important than that is, it is probably the best example of how memory and people’s perception of history can change. . . I’ve come to view it as sort of a 360-degree Rorschach test.”

“The Battle of Atlanta” was created during the heyday of the cyclorama, when mammoth panoramic paintings were displayed in cylindrical wooden buildings around the country, and thousands of customers would line up to immerse themselves in these virtual worlds.

The paintings were generally 50 feet high and 375 feet in circumference. They surrounded the viewer and tricked the eye into seeing three dimensions. As entertainment ventures, they were profitable, though the emerging technology of motion pictures would hasten the end of the cycloramic painting.

A team of 17 German and Austrian immigrants led by Friedrich Wilhelm Heine painted “The Battle of Atlanta” in 1886 in Milwaukee. Members of the group visited Atlanta to photograph and sketch the landscape. They also interviewed Civil War veterans in Wisconsin.

The work was intended to celebrate the Union victory during the July 22, 1864, battle east of downtown, a triumph that became the turning point in the war.

> RELATED: AJC multimedia guide to the Battle of Atlanta

The painting made its way to Minneapolis, and Indianapolis. Before the “Atlanta” was displayed in Chattanooga, it had changed hands, and the new owner, Paul Atkinson, retooled some of the images to create a narrative more palatable to a Southern audience.

He repainted a group of captured Confederate prisoners, and turned them into Yankees, fleeing from the front lines. He also erased a captured Rebel flag, and, as a thumb in the eye to the North, painted a Union flag lying in the dirt. He took out newspaper ads urging the curious to come see “the only Confederate victory ever painted.”

Newsflash: The Battle of Atlanta was not a Confederate victory. Though 10,000 saw the painting (at something like 10 cents a ticket) in its first week in Atlanta, it was also not a commercial victory. Atkinson eventually had to sell the voluminous canvas at a loss to cover the rent owed on his Edgewood Avenue exhibit hall.

The painting was bought by Ernest Woodruff (Robert Woodruff’s dad), who sold it to George V. Gress, who gave it to the city of Atlanta in 1898. It sat around for a while, first out in the weather, then in a substandard wooden building until the city built a “fireproof” permanent structure in 1921, where it remained for the next 96 years.

A dank meme

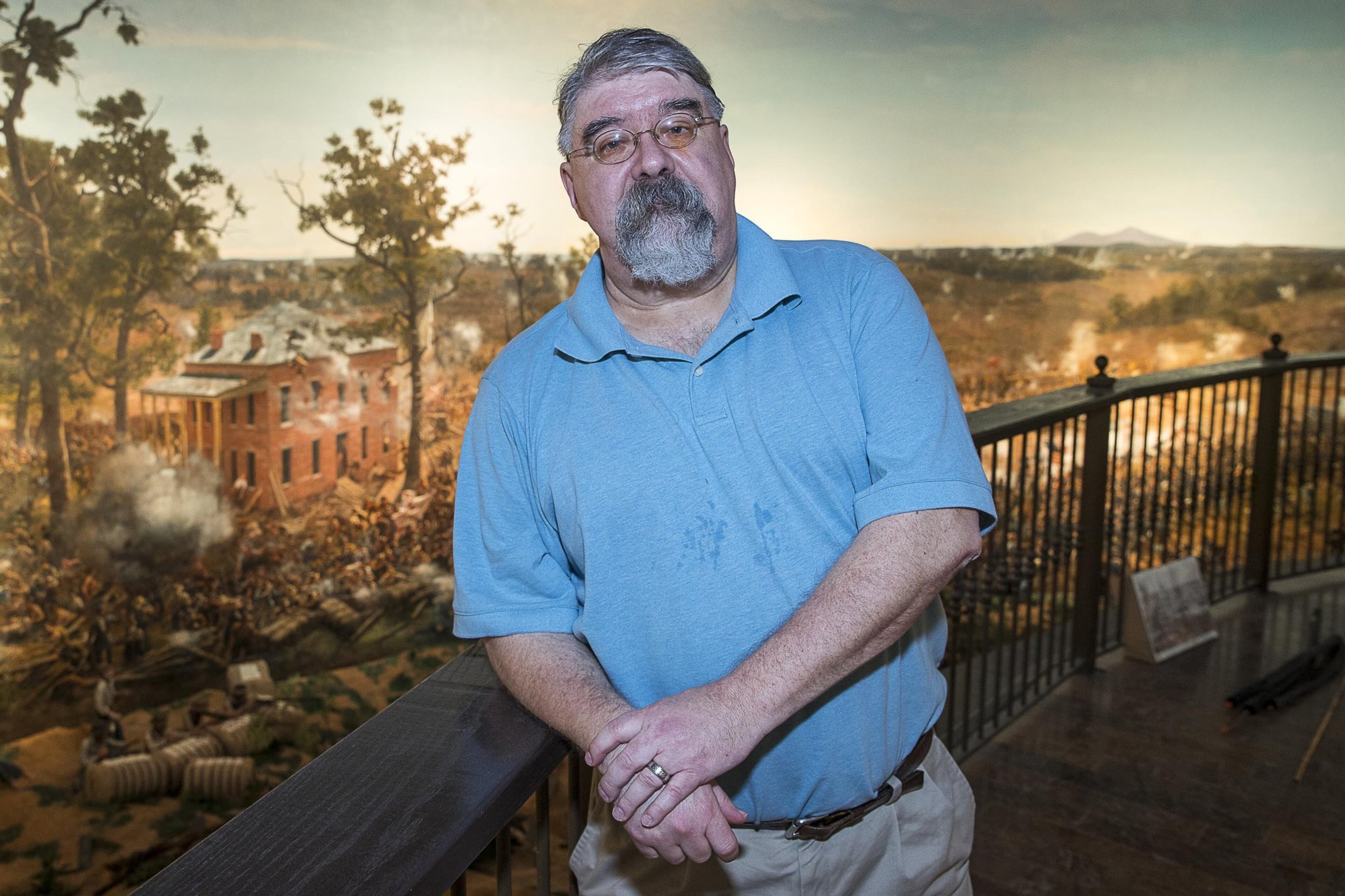

Henry Bryant remembers going to the Cyclorama 45 years ago, when he was a young advertising man fascinated with Civil War history. Bryant has since raised awareness of Atlanta’s role in the war, conducting tours of East Atlanta’s former battlefields with the organization B*ATL.

“You went down into the tunnel and climbed up these stairs and came up into the middle of it, and it smelled like mold,” said Bryant, of the experience. “There was a dampness in the room.”

And then, said Bryant, there was the narration, the “Gone With the Wind” ideology, the “glorious South,” the rendition of “Dixie” at the beginning.

These things changed in 1979 when Mayor Maynard Jackson, over the objections of his constituents, spent $11 million to repair the deteriorating painting and add a rotating viewing platform. Jackson rejected the idea that the painting represented “Lost Cause” propaganda. It was about a battle in which the right side was victorious, he said. “This Cyclorama celebrates our victory,” he told a friend. “It doesn’t celebrate the Confederates. We won.”

Art conservator Gustav Berger conducted the restoration. Berger removed the tons of Georgia red clay that had been trucked in to create a battlefield diorama at the base of the painting, and replaced it with a wood and fiberglass simulation. He cleaned and repaired the 128 plaster soldiers (including the one painted to look like Rhett Butler), cleaned off the mud that had splashed onto the bottom of the painting, repaired tears in the painting and lined the back of the fragile linen with two layers of fiberglass.

Berger also devised a clever "trolley" system to transport the 10,000-pound fabric around the perimeter of the top rail from which it hung. Thirty-five years later, German conservator Ulrich Weilhammer used that same trolley to slowly wind the painting onto two 45-foot spools in preparation for its trip from Grant Park to Buckhead.

“I was told by a lot of people you can’t roll that,” said Christian Marty, the Swiss consultant on the contemporary restoration effort. “They said the paint will come off. I said, ‘We beg to differ.’”

Other conservators also told Marty he needed to scrape the fiberglass off the back of the painting. He didn’t. The fiberglass gave the Belgian linen fabric enough strength to withstand the move.

A new home

In February 2017, a crane lifted the two spools out of the ceiling of the Grant Park Cyclorama building, trucks hauled them across town, and workers unrolled them back onto a new suspension system inside the new Cyclorama building at the History Center.

Then conservators got to work. They cleaned it, sealed it with matte varnish, replaced 7 feet of sky and re-created two vertical sections that had been sliced out prior to 1921. (Due to poor planning, the circumference of the rotunda in the 1921 building was a little too short to accommodate the whole 371-foot-long painting.)

The Civil War-era locomotive the Texas accompanied "The Battle of Atlanta" to Buckhead — it had been part of the Grant Park Cyclorama exhibit since 1927 — and sits in its own lighted terrarium, looking out on West Paces Ferry.

Now that it’s hanging under the proper tension, the profile of the cylindrical painting resembles a cooling tower at a nuclear power plant. This is the “hyperbolic” shape intended by the creators in 1886; the surface swells toward the viewer at the horizon line and recedes at the top and bottom edges, which helps create the 3D illusion.

In its new setting, visitors will see the painting from a viewing platform instead of from a rotating gallery of bleacher seats. Following a 12-minute sound and light presentation, the visitor can stand quietly with the battle scene filling the peripheral vision. The effect is unsettling and awe-inspiring.

Inside that world, it is forever 4:30 in the afternoon on July 22, 1864. Several rebel brigades have broken through the Union line and have seized the DeGress battery, right around where present-day Moreland Avenue crosses DeKalb Avenue. Federal soldiers are launching a counterattack. There are perhaps 3,000 painted soldiers engaged in the teeming action and another 3,000 in the background, some of them suggested by single brushstrokes.

It is more than a battle. It is the fulcrum. Until that moment, President Abraham Lincoln, a Republican campaigning for re-election, was headed toward defeat, the country was tired of war and ready for accommodation, and the Democrats planned a deal with the Confederacy, which would have given us a divided country and continued slavery, said Hale.

“When Atlanta fell, that’s when the wind came out of the sails of the Democratic Party,” said Hale. “Lincoln that summer thought he was going to lose; a lot of other people thought that way too. This painting represents that moment in time, a true turning point in American history, and that’s a lot of what we’re going to be talking about.”

IF YOU GO

Atlanta History Center

10 a.m.-5:30 p.m. Mondays-Saturdays; noon-5:30 p.m. Sundays. $9-$21.50. Ticket sales end at 4:30 p.m. daily. Advance tickets, which are recommended due to demand, are for sale on the History Center website. (You can see the Cyclorama starting Feb. 22.) Tickets are for timed entry. 130 W. Paces Ferry Road, Atlanta. 404-814-4000, atlantahistorycenter.com.

CYCLORAMA HISTORY

1886: Completed by American Panorama Co., Milwaukee.

1887: First displayed in Detroit.

1890: Paul Atkinson of Madison buys the "Atlanta" for $2,500 and displays it in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

1892: Atkinson moves the "Atlanta" to a wooden building on Edgewood Avenue in downtown Atlanta.

1893: Atkinson sells the painting to a Florida businessman.

January 1893: A freak snowstorm caves in the Edgewood structure's roof.

August 1893: The "Atlanta" is sold at auction for $1,100 to collect rent due to the Edgewood property's landlord. Later that year, the painting moves to a wooden structure in Grant Park.

1898: Atlanta businessman George V. Gress gives the Cyclorama to the city.

1921: A new "fireproof" Cyclorama building opens in Grant Park, with a rotunda that is several feet too short in circumference for the complete painting. Historian Wilbur Kurtz wrote that the city utilized a "Procrustean" solution: lopping off several feet of the painting to make it fit.

1979-1982: The Cyclorama undergoes a $15 million renovation, which includes building a rotating gallery for the audience.

2008: Restoration of the Gettysburg Cyclorama prompts calls for new restoration and possible relocation of Atlanta painting.

2011-2012: Advisory group's report lays out options for the Cyclorama.

2014: 150th anniversary of the Battle of Atlanta.

July 23, 2014: Plans are announced to move the Cyclorama from its Grant Park home to the Atlanta History Center, where a structure will be built for it.

June 30, 2015: The last day the Cyclorama is open at its Grant Park location.

December 2015: The locomotive Texas is removed from the Cyclorama building and taken to North Carolina for restoration. Construction of new Cyclorama building begins at the History Center.

February 2017: The painting is wound onto two 45-foot scrolls and trucked across town to the History Center.

May 2017: The Texas is moved to the History Center. The locomotive goes on display in November 2018.

Feb. 22, 2019: The planned opening of "The Battle of Atlanta" exhibit at the Atlanta History Center.