Atlanta photographer focuses lens on restaurant dishwashers

Growing up in a household with four kids, there was no end to chores. Saturday morning always arrived with a laundry list of to-dos: vacuum, dust, scrub toilets. But, every day, there were dishes to wash — by hand.

I don’t know why my parents went years (years!) without fixing the dishwasher. I do know that being assigned kitchen clean-up was preferable to scooping up dog poop in the backyard.

Yet, the household kitchen sink scenario is far different from that of the dish pit, as it’s known in the restaurant industry. Back in that dimly lit station, employees can’t let pots, pans and servingware pile up or soak until someone shakes off laziness. Without dishwashers, the place would come to a halt.

Atlanta-based food photographer Angie Mosier turned her lens toward the people and equipment that keep professional kitchens sanitized in her recent photo essay, “Dish Pit Panorama,” commissioned by the Southern Foodways Alliance as part of the organization’s exploration of food labor in the South. It was on display last month at the University of Mississippi.

At first glance, dish pits look a lot alike, with three separate compartments to clean, rinse, and sanitize and dry – along with a commercial dishwashing machine. Yet, the distinct contents that move in and out of each pit tell much about the place, providing Mosier the angle for her photo series.

Mosier visited five Atlanta establishments — Home Grown, Matthews Cafeteria, Little Tart bakery, Kimball House and fine dining restaurant One Flew South at the airport.

At popular Cabbagetown breakfast spot Home Grown, she learned through its dishwashers that “having breakfast kinds of food can be special challenges, because you have all these creamers and syrup pitchers. Little things that have jelly in them — things that are hard to get clean sometimes,” Mosier observed.

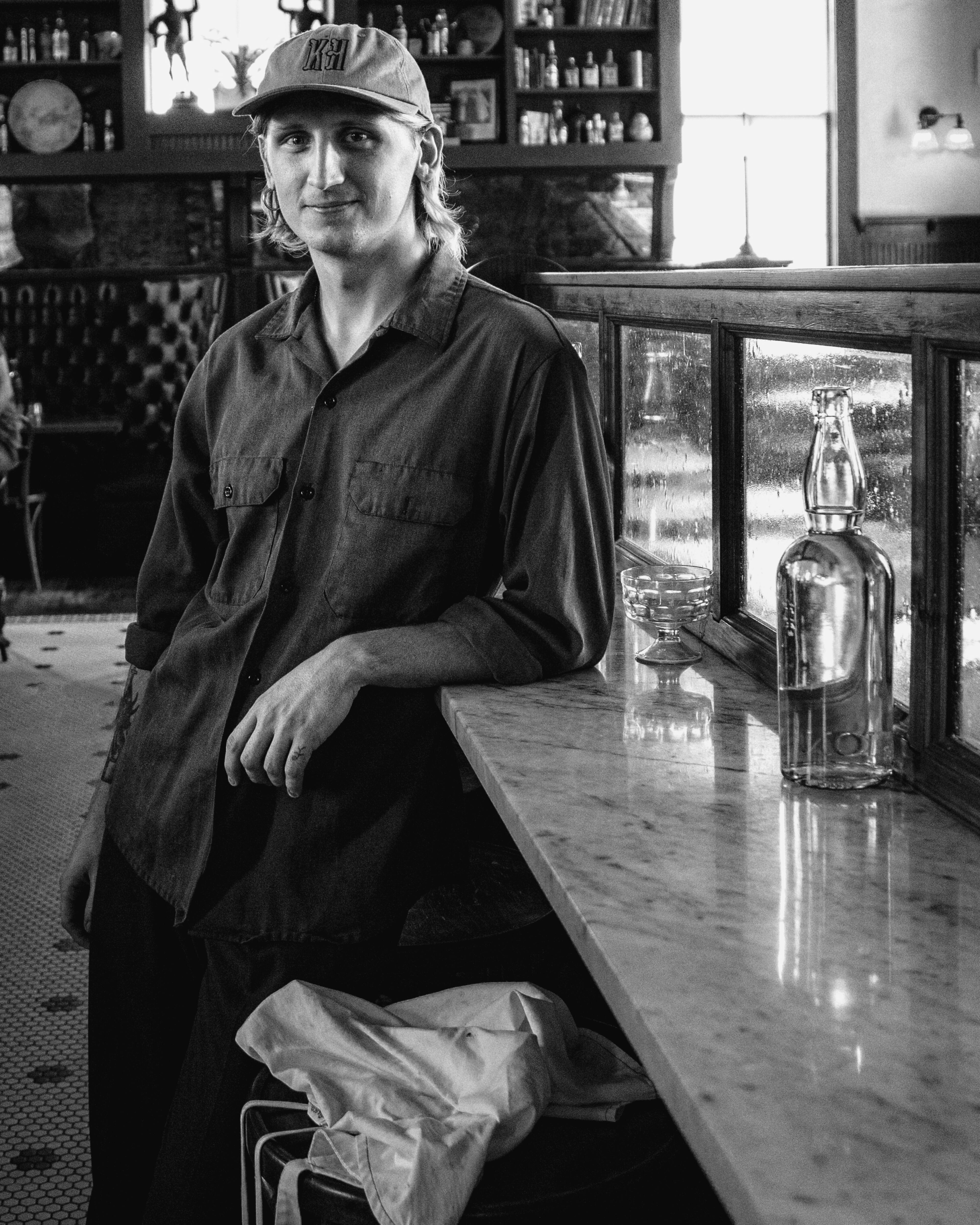

This scene contrasts with what Kimball House dishwasher Jeremy Jones faces in his job cleaning crystal cocktail coupes with delicate etching, or the care that Little Tart dishwasher Brandon Early gives to handling measuring spoons, offset spatulas, whisks and pastry rings in a bakery setting.

A trip to the basement kitchen at Matthews Cafeteria, open since 1955, and still run by the same family in the same location on Main Street in Tucker, was a trip back in time.

“Time stopped in a lot of ways down in that kitchen,” she said. “They have all this old equipment that they’ve just taken care of, that they’re still using after all this time.” This includes an Auto-Chlor, a now widely used brand of commercial dishwashers. But, she noted, “Matthews was the first restaurant in Atlanta to get an Auto-Chlor machine.”

In documenting a work setting that diners rarely can access, Mosier also allowed viewers to see a labor force we often overlook.

“Usually, I’m shooting an executive chef or a sous chef or a line cook,” she said. “I never get asked to shoot the prep cooks or the dishwasher. You probably think about the dishwasher, and the guy who takes out the garbage, the least.”

She said she hoped that the project also shed a light on dishwashers as people, not just as dishwashers. “They all have something else in their life that they are interested and passionate about,” Mosier said.

Hector Noel Cruz, a 15-year employee at Matthews, likes to fish. Kimball House’s Jones earned his nickname, Pit Boss, not just because he rules the dish pit, but for his love of the mosh pit at punk rock shows.

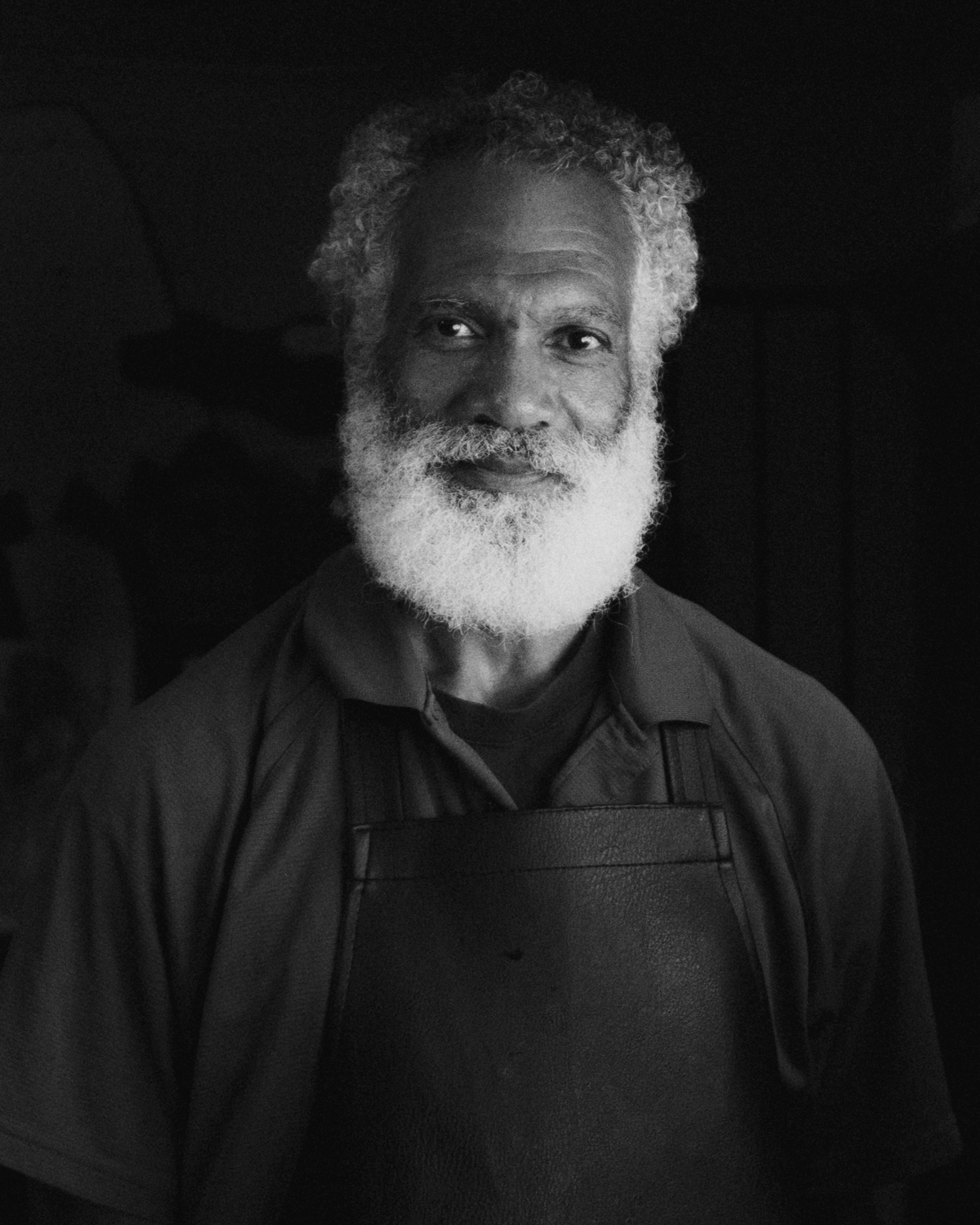

Dishwashers have interesting pasts, including that of Home Grown’s Eric Mason, whose experience modeling for Atlanta-based black hair care product company Bronner Bros. became apparent when he let Mosier take his portrait. “He immediately stepped into the perfect light,” she said. “The way he would slightly move his head, I said, ‘You have had your picture taken before a lot. You know how to move.’”

Some, like Early, Little Tart’s aspiring rapper, whose stage name is LaBezzieB, have future plans that don’t involve the dish pit.

But, when work calls, these employees perform like rock stars.

Mosier recalled how, at Home Grown, Mason and his dish pit peer, Zachary “Z” Huff, “were doing this really great sort of dance of getting staying out of each other’s way” as they sprayed plate after plate, tackled a multi-foot stack of dirty plastic tumblers, and removed clean dishes to make room for the next round.

“Everyone that I photographed was proud of the work they were doing,” Mosier said. “They said, ‘You get this sense of accomplishment. We just know what we got to get done.’”

The high-tempo pace and gritty work of dishwashing are the reasons Mosier shot the series in black and white. “They’re moving fast,” she said. “They’re usually working in a pretty dark place of the kitchen. So, it’s hard to take super sharp photos. I could have used an on-camera flash, but I chose not to, because I was enjoying the graininess of it all. It makes so much sense to do it in black and white, because it’s sort of timeless.”

Timeless, indeed. Wherever there’s food, dirty dishes are bound to follow.

RELATED:

Read more stories like this by liking Atlanta Restaurant Scene on Facebook, following @ATLDiningNews on Twitter and @ajcdining on Instagram.