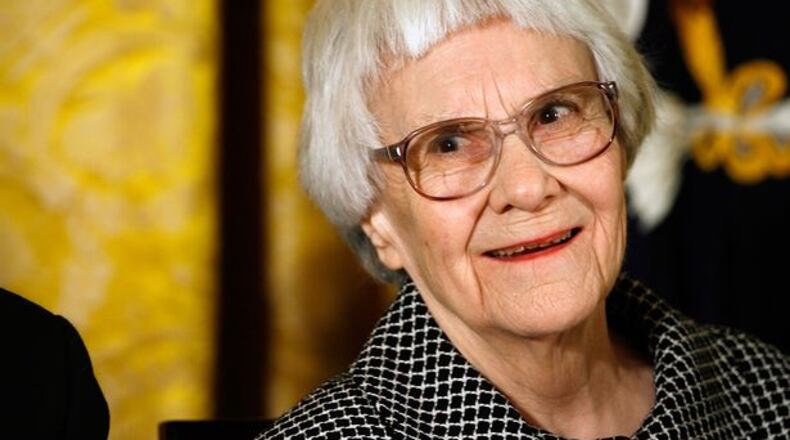

The mysteries surrounding Harper Lee continue to deepen.

The first mystery was how in 1960 this Alabama author wrote a book that changed American literature and then, seemingly, wrote nothing else.

Then, in 2015, the next mystery bubbled up when her lawyer, Tonja Carter, discovered the manuscript for a second novel, “Go Set a Watchman,” that had been missing for decades. How did it disappear? Mystery.

The third mystery was known to many people in Alabama but unknown to the world at large.

What happened to the true crime novel that Lee worked on for years?

Journalist Casey Cep unpeels the story of Lee’s last, failed effort in “Furious Hours,” which she will discuss during a visit to the Margaret Mitchell House on May 16.

Cep’s book is a deeply reported non-fiction account of a sharp-dressed preacher accused of being a serial killer, a murder in front of 300 witnesses and of Lee’s attempt to package the tale into a real-life sequel to “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

The saga took Lee (and Cep) to Alexander City, Alabama, home of the Rev. Willie Maxwell, the black preacher who had life insurance policies on five people who died in unlikely ways. Despite the deaths of his first wife, his brother, his second wife, his nephew and his adopted daughter, Maxwell eluded prosecutors. He was defended by a non-judgmental white lawyer named Tom Radney, who also, coincidentally, helped Maxwell (and himself) collect on those policies.

The tale becomes more bizarre when Maxwell is shot three times in the face at the funeral of one of his alleged victims. The shooter is successfully defended by none other than Tom Radney.

Cep’s reporting ranges far and wide, from Alabama history and the impoundment of Lake Martin to the unscrupulous life insurance grifters of the industry’s early years, but she spends the most time on Maxwell, Radney, the funeral vigilante Robert Burns and Lee herself.

She tracks Lee’s conversations with her sources, and notes that Lee used the same reportorial skills she brought to bear while helping her friend Truman Capote interview the residents of Holcomb, Kansas for his own true-life crime book, “In Cold Blood.”

She also notes Lee’s growing frustration with the project. To begin with, there was no protagonist with whom the readers could identify. “She knew all too well that the story of a black serial killer wasn’t what readers would expect from the author of ‘To Kill A Mockingbird,’” Cep writes.

Credit: file

Credit: file

While tracing Lee’s steps, Cep discovered the same reticence in Lee’s acquaintances that has stymied other reporters. “People were hoarding all of their experiences with her, keeping them private, but that has diminished some in the time since she died,” said Cep, 33, during a recent conversation from her home on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

A few leads never panned out, including the indication that Lee tape-recorded her interviews. Those cassettes haven’t turned up yet. “There’s nobody who would be more excited to hear those tapes than I,” said Cep, pointing out that of the few interviews Lee ever gave, only 15 minutes are on audiotape.

Most tantalizing of all is whether “The Reverend,” which is what Lee called her long-pursued book, exists. Did it end as a sheaf of notes and bitter disappointment? The answer is locked away with Lee’s literary papers.

But some friends that Cep interviewed doubted that Lee, hampered by depression, alcohol and writer’s block, ever finished the project. “There are some people who knew her well who just say there’s no way in such a dark time in her life that she could have brought this book together.”

By 1981 Lee’s sister Louise “Weezie” Conner decided go take matters in hand, and invited Lee to stay in Eufala, and kept her focused on her writing. Louise “won’t even let me go fishing until late afternoon,” Lee wrote to her friend Gregory Peck, as she complained about the progress of the book and the demands on its performance. “My agent wants pure gore & autopsies, my publisher wants another best-seller, and I want a clear conscience, in that I haven’t defrauded the reader.”

PREVIEW

Casey Cep discusses "Furious Hours" at the Margaret Mitchell House. 7 p.m. Thursday, May 16. $10; $5 members; free to Atlanta History Center insiders. 979 Crescent Ave., Atlanta. www.atlantahistorycenter.com.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured