Since Pat Conroy's death in 2016, the celebrated author of "The Great Santini" and "The Prince of Tides" has been warmly remembered in an authorized biography ("My Exaggerated Life" as told to Katherine Clark) and an anthology of recollections by writers including Rick Bragg and Ron Rash ("Our Prince of Scribes"). But Michael Mewshaw, author of 22 books and once a close friend of Conroy's, presents a different portrayal of the writer in his new memoir, "The Lost Prince" (Counterpoint Press, $26).

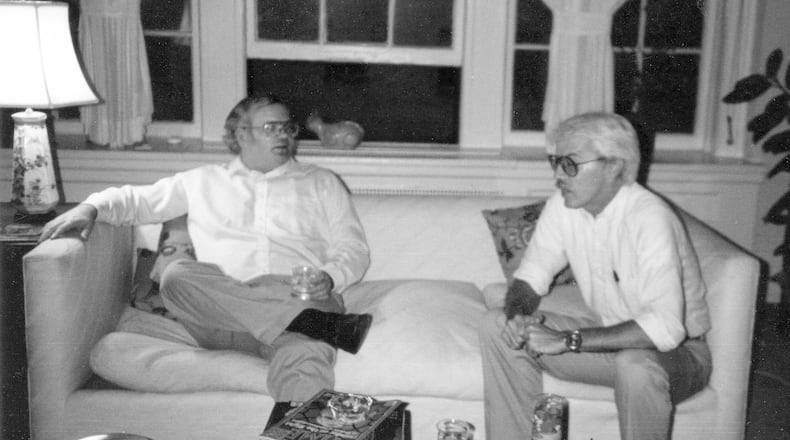

The two met while living in Rome during the 1980s and swiftly bonded over their similar histories. Both men grew up in dysfunctional families with abusive parents and became involved with pregnant women in college, only to be later dumped. For years, they spoke nearly every day, revealing intimate details of their lives to each other. They created characters based on each other in their novels. Their families vacationed together. Mewshaw was godfather to Conroy’s daughter, Susannah.

But according to Mewshaw, all that ended when Conroy suffered a sort of mental breakdown during the writing of “The Prince of Tides.” After isolating himself from his family for an extended period of time, claiming he needed solitude to write, Conroy threatened suicide if Mewshaw didn’t tell his wife, Lenore Conroy, that he wouldn’t be home for Thanksgiving. “Asking me to tell Lenore that their marriage was over, in effect,” Mewshaw said. What Conroy didn’t tell Mewshaw is that he was having an affair at the time. Mewshaw reluctantly did as Conroy asked, and immediately afterward his famous friend ghosted him for six years, claiming Mewshaw sided with Lenore in the divorce. Despite a couple of efforts to reconcile, their friendship proved irrevocably broken.

Years later, when Mewshaw was working on a collection of essays about writers who had influenced him, Conroy encouraged Mewshaw to include the story of their friendship. It wasn't a good fit, Mewshaw said. Conroy was a contemporary, not an influence. But the idea of telling their story stayed with him, and after Conroy died, Mewshaw began researching the author's archives at the University of South Carolina. He was shocked to learn that during their time together in Rome, Conroy was engaged in a prolific and virulent letter-writing campaign against Lenore's ex-husband, who was waging a custody battle for his children and was later accused of sexually abusing one of his daughters, although he was never tried. Conroy's failure to mention that battle of words during their daily conversations, Mewshaw said, illustrated Conroy's description of himself as "the most falsely open person that I would ever meet" and underscored just how complicated Conroy truly was.

“The Lost Prince” is Mewshaw’s attempt to capture the complexities of Conroy’s character.

“This was certainly the most difficult book I’ve ever written because I wanted it to express my own lasting affection for Pat, but at the same time to present him honestly or at least honestly as I witnessed it. As I say in the book, Pat urged me to write about our relationship for better and for worse, as painful as it would be for both of us, and that’s what I did,” said Mewshaw.

“He was a complicated guy and a conflicted guy. To me, that makes him fascinating. Much more fascinating than the Li’l Abner image he projected or the huggy bear image most people have of him.”

AJC: You and Conroy were expatriates in Rome during the ‘80s. That must have been a thrilling time.

Mewshaw: It's so extraordinary to think of Pat, who was so rooted in the South, as having spent nearly four years living in Rome and frequently going back to visit. He's a very, very Southern writer, a very American writer, and yet I think that experience was deeply influential in his work and in his life.

It’s been said that an expatriate is someone who’s trying to cure one form of alienation with another. I think that applies to me, but I think it also applies to Pat. I think that as rooted as he was in the South, he was also, because of his family history, slightly apart from or alienated from the world around him in the South.

It’s often assumed, because Pat was an amiable, friendly, at least on the surface, easygoing guy, that he had kind of recovered from a childhood of abuse. But I don’t think you ever recover from that kind of experience. I think he had serious issues with depression and with manic behavior, what people now call bipolar behavior, and I think it was a direct result of his childhood. I think Pat understandably had psychological issues that stemmed from his experience and it influenced his decisions later in life and many of those decisions came back to haunt him.

AJC: In what way?

Mewshaw: Well, where do I start? You know, in alcoholic families, or dysfunctional families, there is a notion that among the children, there is a hero rescuer. That was Pat's role in his family. He was the hero protector. He was the person who wanted to protect his mother, who wanted to stand up to his father. And to a great extent, he did that. But then he continued to do it in many of his relationships with his future wives. He was a rescuer of damsels in distress.

AJC: You also came from a dysfunctional family and were a hero rescuer who, like Conroy, became involved with a pregnant woman in college. Does that explain how you two connected so deeply?

Mewshaw: Our pasts were so hauntingly similar. But there was a fork in the road. That experience made me determined to never again find myself in that kind of situation where I was trying to rescue a damaged person. And I think that's where Pat took the other fork. He continued for the rest of his life, attempting to be that knight in shining armor. I think he involved himself over and over again in difficult, conflicted, confrontational relationships and felt it was up to him to right wrongs, many of which he misperceived and misunderstood. I think you can see it in his books. There are so many hero rescuers in his books, and problems are solved more or less miraculously by someone taking a heroic stand and forcing authorities to change the course of events.

AJC: Conroy is fairly dismissive of you in “My Exaggerated Life.” Did that influence your portrayal of him in “The Lost Prince”?

Mewshaw: No, I didn't read it until I'd finished my book. The only thing that it changed is there were things that Pat said factually that needed to be addressed, like talking about spending nights going out to dinner with Gore Vidal. That never, never happened. Or Pat talking about meeting Italo Calvino, the famous Italian writer who barely spoke English, in a bar and having a conversation with him. Believe me, that never happened. There were other things like that. Saying that when I first met him, I confused him with Frank Conroy, and for the first hour of our lunch at his house, he pretended to be Frank Conroy. I mean, just on the face of it, it doesn't make any sense, and it's not true.

AJC: How much do you think Conroy’s exaggerations were just him taking literary license or telling tall tales?

Mewshaw: I think where it gets troubling is when these tall tales have real-world consequences for the people around him. To say, which he did over a period of decades, that his daughter Susannah was stolen from him. That she was a lost child, to put that in the dedication of his books and tell NPR and People magazine and for no journalist to ever check to say to the girl, is this true? Then you're talking about something that is potentially injurious to a 13- or 14-year-old girl. It's fine to tell a tall tale in your writing, but to tell a tall tale about a person, this little girl, is a different kettle of fish.

To speculate in “My Exaggerated Life” that … Lenore must have known that her daughter was (allegedly) being sexually abused because (Lenore) was there in the house, still married to (her ex-husband) — that is a hideous implication that is factually untrue. The alleged sexual abuse happened many years later when her daughter was having a family visitation.

AJC: You and Conroy were so close. It must have left a huge void in your life when he ended the friendship.

Mewshaw: It is often difficult for men to talk about love for other men. We're supposed to keep our feelings in a lock box. But if you've read Pat's letters to me, he loved me, and I loved him, too. The only thing I can compare this experience to was that college girlfriend of mine, who after I had lived with her for six months and helped her out when she was having this baby, dumped me. At least I saw her again. Pat did the same, and for six years, we had no contact whatsoever. He simply wouldn't reply to letters or emails or phone calls or messages passed through friends. It was extraordinarily hurtful. Of course, I tried to review in my mind, to understand what I could have done wrong. To what extent was I responsible? To what extent did he perceive me as not worthy of his friendship?

AJC: How would you characterize Conroy’s literary legacy?

Mewshaw: There are writers that will last because their work left the literary landscape changed, whose style or genius or the content of what they wrote was so different that nobody could write the same after. That was not the kind of writer Pat was. Pat was much more influential in a more democratic way. He had thousands of fans. He'll be remembered for that. He touched the hearts of millions of readers. They were equally touched by his personality and his presence. That is no small achievement. That is an enormous achievement.

Questions and answers were edited for brevity and clarity.

EVENT PREVIEW

Book signing. Michael Mewshaw signs "The Lost Prince." 6 p.m. March 5. Free. Posman Books, Ponce City Market, 675 Ponce de Leon Ave., Atlanta. 470-355-9041, posmanbooks.com.

IN OTHER NEWS:

About the Author