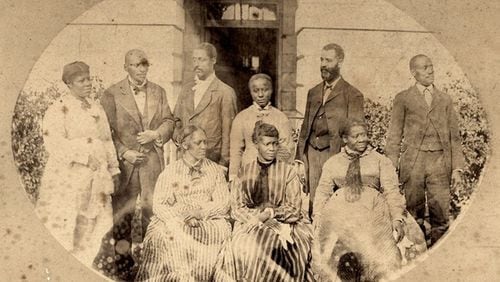

In the sepia photograph, there’s not a stain on the crisp, white apron tied around Daisy Bonner’s trim waist and barely a wrinkle. Someone may have taken her picture before she cooked lunch for her employers or perhaps, she put on a fresh uniform just for the portrait.

The equally spotless white collar of her dress frames her youthful brown face. She’s standing in the front yard of a clapboard house the color of her apron, a house most likely in Meriweather County, Georgia, where she worked. Her smile is faint, its intent hard to read. Was she pleased to take this photo? Or was it an interruption in an otherwise busy day when perhaps a pile of unwashed turnip greens crowed the kitchen counter waiting for her hands to clean them.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt loved the way Bonner prepared greens. She worked for him at the “Little White House,” Roosevelt’s Warm Springs, Georgia retreat from the 1920s until his death there in 1945. At a time when domestic work was one of the few means of employment for black women, particularly in the South, this was considered a prestigious post for a black woman. And an influential one. Bonner believed Southern cooking, the way she’d learned to do while growing up in west-central Georgia, might help restore strength to a president living with paralysis from polio.

“She got him hooked on all kinds of Southern specialties, especially pigs’ feet,” said Adrian Miller, author of “The Presidents’ Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families from the Washingtons to the Obamas.” “We have newspaper accounts and observers accounts that he loved the pigs’ feet that she made. She would broil them, split them and then butter them.”

Bonner’s story is one of several Miller will share from “The President’s Kitchen Cabinet,” Wednesday, at the Atlanta History Center. But while Miller, a former deputy policy director for President Bill Clinton, will talk about the lives of the black people who cooked for presidents, he’ll also talk about the food they sometimes prepared, especially — as was the case with Bonner — soul food. Miller won a James Beard Award in 2014 for his first book, “Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time.” He’s currently researching a book on the African American contribution to the legacy of barbecue.

Like many who work behind the scenes, Bonner never had her story fully told. The bits and pieces Miller found while researching “Kitchen Cabinet,” were essential to telling the broader story of how staff often impacted the most powerful men in the nation, and in some ways, their policies. Including cooks, chefs, stewards and attendants, Miller found documentation showing that at least 195 African Americans served U.S. presidents — from the first president to the 44th.

“They gave these presidents a window on black lives they may never have otherwise had,” Miller said. “Now, not every president opened up that window and took a peek, but for the few who did, I think our nation is immeasurably better for it.”

There was Zephyr Wright, who, as Miller wrote, sat in the VIP box at the inauguration of her longtime employer, Lyndon B. Johnson. Though brought in to be the personal “family cook” for the Johnson’s, a role she’d played for 21 years in Texas while Johnson ascended the political ladder, she soon “bested” the French chef who remained in charge at the White House immediately after the Kennedy administration. The Johnson’s palates were more attuned to Wright’s Texas staples, such as hash and Pedernales River chili. The French chef, while classically trained, couldn’t compete.

But Wright’s lasting contribution came through her familiarity with the president. She told him about her humiliating experiences with segregation and racism. The Johnsons witnessed some of them, such as Wright being denied a room in the same hotel as the President and first lady, Lady Bird Johnson, solely because Wright was black.

“He actually used her Jim Crow experiences to garner support for the 1964 Civil Rights Act,” Miller said. “And when he signed the bill, he gave her one of the pins and said, ‘You deserve this as much as anyone.’”

Several presidential African American chefs were trained in French techniques, most famously James Hemings, the enslaved chef of Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson brought Hemings to France to learn the art of the cuisine.

But soul food and southern food were part of presidential diets, too. Miller plans to engage that debate at the history center as well: What makes a dish southern versus soul, and can they be both? It’s an argument as heavy as a cast-iron skillet.

Bonner was a master at those vernacular staples, Miller said. When he went to Warm Springs on a research trip for the book, he saw what is believed to be the grocery list for the last trip Roosevelt made there before his unexpected death. It included “4 hogs feet.” He died on April 12, 1945, in the Little White House awaiting a lunch prepared by Bonner. She’d made a cheese soufflé. Before she could bring it from the kitchen to the dining room, he complained of an excruciating headache and slumped at the table. He was pronounced dead about two hours later. Bonner claimed the soufflé did not fall until Roosevelt took his last breath.

“She was so moved by his death, that if you go to Warm Springs today, you’ll see her handwriting on the wall where she says, ‘Daisy Bonner cooked the first meal and the last one in this cottage for … President Roosevelt.’”

Thirteen years after Roosevelt’s death, Bonner died also in April in Warm Springs.

“I really don’t think a lot of people know this history,” Miller said. “It’s just another example of how African Americans have been essential to building the foundations of American food as we understand it, and another example of how black history is American history and, in this case, presidential history.”

Perhaps there’s no more fitting time to retell those stories as right now, as the nation gears up to elect its next president.

EVENT PREVIEW

Adrian Miller

“The Presidents’ Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families from the Washingtons to the Obamas” and “Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time”

7 p.m. Wednesday. $10. Atlanta History Center, 130 W. Paces Ferry Road NW, Atlanta. 404-814-4000, atlantahistorycenter.com.

Daisy Bonner’s Cheese Soufflé

Author Adrian Miller says this is the recipe cook Daisy Bonner made for President Franklin D. Roosevelt the day he died at the “Little White House” in Warm Springs. Miller writes that Bonner always served this with baked tomatoes, peas, plain lettuce salad with French dressing, Melba toast and coffee.

Makes 5 servings

1 tablespoon butter

2 heaping tablespoons flour

Pinch of salt

1/2 teaspoon prepared mustard

1/2 cup whole milk

3/4 cup grated sharp cheddar cheese

5 eggs, separated

1 teaspoon baking powder

1. Heat oven to 375 degrees F

2. Melt butter in a saucepan and blend in flour, salt and mustard. Gradually add the milk, whisking constantly, to make a thin sauce.

3. Beat egg yolks slightly and add them and the cheese to the sauce. Stir to combine.

4. Set aside to cool until ready to bake.

5. When ready to bake, beat egg whites and baking powder together until stiff.

6. Fold the egg whites into the cheese mixture.

7. Transfer the mixture to an 8x8-inch baking dish and bake for 30 minutes.

8. When soufflé is done it should be very high and brown but soft in the middle.

Serve immediately.

(Recipe Courtesy of Adrian Miller)

About the Author