‘Smokelore’ a deep, tasty dive into the history of ‘cue

Before he was even born, Jim Auchmutey was genetically predisposed to love barbecue.

The Atlanta writer’s paternal grandfather was a pitmaster for the Euharlee Farmers Club barbecue in Bartow County. “Daddy Bob” was so renowned for his pig cooking skills, he was featured in an article on the topic in the Saturday Evening Post in 1954. But Auchmutey’s mother’s family was in on the pork processing business as well. They ran a slaughterhouse in Washington County and made hot country sausage, which little Jim helped deliver in the summer months.

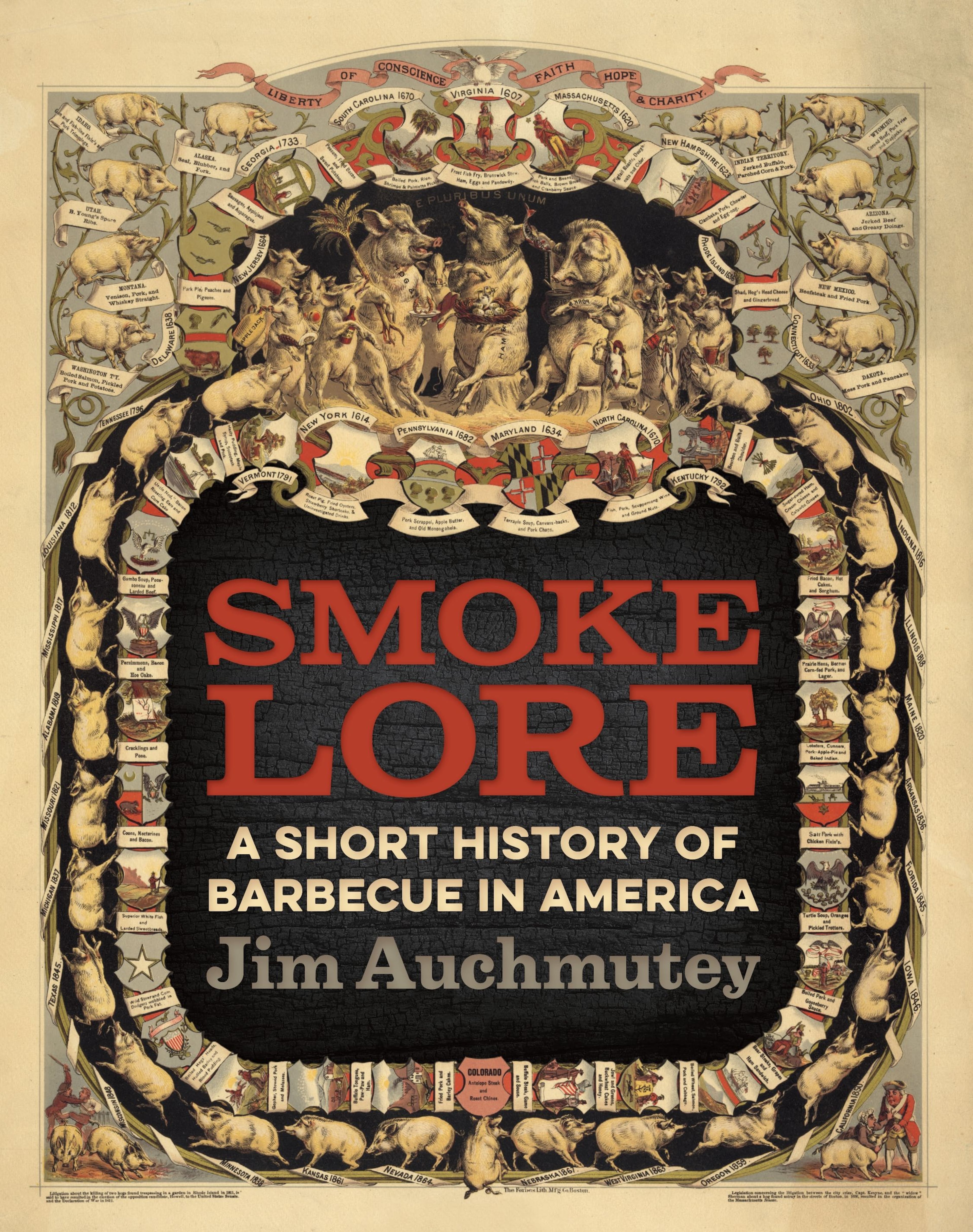

"I have pig in my blood on both sides," says Auchmutey, an expert on the art of barbecue and the author of "Smokelore: A Short History of Barbecue in America," which publishes June 1 by the University of Georgia Press.

A companion piece to "Barbecue Nation," the Atlanta History Center exhibition that runs through Sept. 29 and which Auchmutey guest curated, the book chronicles the evolution of barbecue from its indigenous Caribbean origins to agrarian barbecue clubs, political rallies, roadside restaurants, backyard barbecues and barbecue competitions.

>> RELATED: History Center's 'Barbecue Nation' looks for America in smoky meat

>> RELATED: Atlanta's reputation on the rise as 'a serious barbecue town'

The heavily illustrated book is filled with colorful vintage photographs; advertisements; menus; postcards; covers of matchbooks, cookbooks and magazines; blueprints for building a backyard cooker; and tons of signage, much of it comically pig-centric, like the one from Leonard’s Barbecue in Memphis that shows, as Auchmutey describes it, “a pig lying on its side over a bed of coals, looking strangely content as if it were lounging in a sauna.”

>> RELATED: Spring Dining Guide: Atlanta barbecue restaurants

A seasoned journalist who spent 29 years at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Auchmutey brings a scholar’s nose for research to “Smokelore,” but his conversational tone and playful tangents make it an entertaining and enlightening read. Where else would you find a lengthy barbecue playlist that includes Elvin Bishop’s “Barbecue Boogie,” Bo Carter’s “Pig Meat Is What I Crave” and Outkast’s “Skew It on the Bar-B”?

By no means a cookbook, “Smokelore” nevertheless does contain more than two dozen recipes, including the Memphis dry rib rub from Rendezvous in Memphis, the brisket from Franklin’s Barbecue in Austin, Texas, and the kimchi slaw at Heirloom Market BBQ in Atlanta.

But perhaps no recipe gives readers pause like Mrs. Dull’s Brunswick Stew from 1928. The first food editor for the Atlanta Journal begins her recipe by advising cooks to clean the pig’s head by removing its teeth and gums, and she ends it by recommending a half-pound of butter get tossed into the mix before it’s served. I may never look at Brunswick stew the same after reading that.

Among the ‘cue-related topics Auchmutey explores is what he calls the Great Carolina Divide, a topic of lively debate among Southern barbecue aficionados. What it boils down to is, eastern North Carolina, which Auchmutey says has “probably the oldest barbecue tradition in America,” prepares its delicacy using the whole hog and serves it with a “tomato-less sauce that is primarily cider vinegar with a whole lot of seasonings in it.” Meanwhile, in western North Carolina, they only cook the pork shoulder and use a vinegar-based sauce that has a little ketchup in it.

“To hear the people in North Carolina talk about it,” Auchmutey says, “you would think this is like the Hatfields and the McCoys. But the fact is, the sauce you find in Lexington and the Piedmont actually is fairly similar to the sauce you find in the west. It’s primarily a vinegar sauce with a lot of seasonings; it just has this red stuff in it.

“To complicate matters, down in South Carolina, where you also find a lot of vinegar sauce, there is that specialty that you find in the Midlands around Columbia that is a mustard sauce. But come to find out, it’s actually just about as deeply rooted in Georgia. If you look at old cookbooks from the 1800s, a lot of Georgia barbecue sauces have mustard in them. The oldest existing barbecue sauce brand in America, which is out of Macon, called Mrs. Griffin’s, has mustard in it. There’s a lot of mustard in the sauces around Columbus. I refer to the mustard sauce as the Georgia-South Carolina mustard sauce.”

And that raises the question, what makes Georgia’s barbecue distinct? According to Auchmutey, it typically consists of chopped pork with a tomato-vinegar sauce, “but the single most identifying thing about it is the Brunswick stew. Nowhere else in the world is Brunswick stew so central to the barbecue tradition as it is in Georgia.”

If there’s one big takeaway from “Smokelore,” it’s that although “American barbecue as we know it took shape on the Southeastern seaboard,” says Auchmutey, “(it’s) a much more diverse thing and a much more widespread thing in America than a lot of us Southerners presume.

“The fact that you can find really good Texas-style brisket in Brooklyn right now is really interesting to me,” he says.

Auchmutey acknowledges that many of the venerable old-school barbecue pits are slowly dying out, but he says the news isn’t all bad. In fact, he thinks this is the best time for barbecue in American history.

He credits two groups of people for his optimism: competitors on the barbecue contest circuit who have "taken their passion, their hobby, their enthusiasm and turned it into a commercial thing," and the folks behind the craft barbecue movement like Aaron Franklin in Austin, Texas, and Bryan Furman at B's Cracklin' Barbecue in Atlanta, which burned earlier this year but is working on plans to open a pop-up while it rebuilds.

“I think even though it’s sad that the really old, traditional places are closing, so many places have popped up in their stead and that’s the nature of life and the nature of barbecue,” Auchmutey says.

When pressed to pick his favorite barbecue restaurants, Auchmutey gives the nod to Fresh Air in Jackson for best ‘cue in Georgia, but he admits that has a lot to do with his childhood memories.

“One of my favorite uncles, Uncle Earl, he was a career Air Force officer in Warner Robins. And when we would go see him or he would come see us, there would often be a stop at Fresh Air to bring some barbecue. So I associated it with fun visits with my Uncle Earl. Uncle Earl was the kind of guy who told funny, dirty jokes. So Fresh Air Barbeque reminds me of funny, dirty jokes. And, of course, so much about food seems to be about memories and associations like that, and I think that is particularly true of barbecue.”

Asked for his all-time favorite barbecue joint, Auchmutey stalls a bit before answering.

“I love the whole hog you get in eastern North Carolina. I love the rib tips you get in Chicago. I love the burnt ends you get in Kansas City. God knows I love the smoked sausage and brisket you get in Texas,” he says before falling silent, emitting a loud sigh and then blurting: “Payne’s Bar-B-Que in Memphis. It’s in a converted gas station on the southside of Memphis. They have, to me, the best barbecue pork sandwich on Earth. And what I love about it is, it’s really smoky. They mix the inside and outside meat. When you order it, Flora Payne or one of her children in back there whack it on a board, mixing the inside and outside meat. And they serve it with this slightly mustardy and slightly hot coleslaw. All of those things come together in a wonderful way.”

If that description doesn’t inspire a trip to your nearest barbecue purveyor, you’re either vegetarian or dead.

AUTHOR EVENTS

Jim Auchmutey. "Smokelore: A Short History of Barbecue in America." 6 p.m. reception, 7 p.m. author's talk. May 23. $10. Atlanta History Center, 130 W. Paces Ferry Road, Atlanta. 404-814-4000, atlantahistorycenter.com.

Lecture on barbecue and politics. 7 p.m. June 25. Free. Carter Presidential Library & Museum Theater, 441 Freedom Parkway, Atlanta. 404-865-7100, jimmycarterlibrary.gov.

NONFICTION

‘Smokelore: A Short History of Barbecue in America’

by Jim Auchmutey

University of Georgia Press, 280 pages, $32.95