Kiese Laymon's visceral "Heavy: An American Memoir" conveys sweat, shivers and raw pain. His book is of the flesh, about how what happens to our flesh gets inscribed on our souls, and how what we're told to think about our bodies gets branded on us as fiercely as the mark of a hot iron.

On nearly every page, he reminds us of how his bulk takes up energy in his brain. He steps on the scale at critical moments in this memoir, and nearly every time the climbing numbers chasten him, pound by increasing pound. I know the feeling — who in America feels happy with his or her weight? — but it’s rare to see it conveyed in African-American writing by men. His language is earthy, pungent. He spends a lifetime trying to tamp down his shame and his flesh.

Heaviness isn’t just physical in this book, but also existential and political. Laymon knows that his black male body radiates a different kind of energy to the outside world. Shortly after 9/11, Laymon feels an emotional release, walking through Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan.

“For the first time in my life, I experienced not having the most fear-provoking body in a contained American space. Of course, folks on that train were still afraid of big black bodies like mine, but they were more afraid of brown folks who ‘looked’ like Muslims.”

Black bodies take up space in America, and Laymon reminds us that this geography is as much psychic as physical. “Heavy” is a coming-of-age memoir set in, and haunted by, a very particular space: Jackson, Mississippi. Laymon grew up there. Its racial and gender dynamics are written on his heart. Though he eventually flees to Oberlin College in Ohio, and then Vassar College in upstate New York, he carries Jackson with him — its slang, slurs, senses of blackness and gender and loss, and its deceptions about race — wherever he goes.

But Laymon is also attempting to write his memoir onto one person’s heart: his mother’s. “Heavy” is conceived as a letter to her, following in the tradition of black intellectuals imagining their most heartfelt, terrifyingly intimate manifestos about America to their black relatives, from James Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time” to Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “Between the World and Me.” Like Baldwin and Coates, Laymon refuses to lie about America’s broken promises to itself, and it won’t offer easy comfort or redemption narratives. America’s failures regarding its African-American citizens, Laymon tells his mom, are the country’s fault lines writ large, and he’s not at all sure we can close the gaps.

Laymon’s mother, a professor at Jackson State University, grounded him in black literature and philosophy, radical politics, black Southern identity and a deeply rooted feminism that absorbs and feeds him. (It’s telling that black women such as Margaret Walker Alexander and especially Toni Cade Bambara are his touchstones and reference points.) As he tells his mama and us, “You gave me a black Southern laboratory to work with words. In that space, I learned how to assemble memory and imagination when I most wanted to die.”

Right there we see both the promise and pain of her lessons. For while it’s true that Laymon and his mother have an incredibly intimate relationship, she also beat him mercilessly, lambasted him about his body, stole from him to support her gambling addiction (which he eventually absorbed) and thoroughly failed to give him good models for healthy living and loving.

We think of intimate relationships as our ideals. But for so many of us, our most intimate relationships aren’t ideal at all, or even good. They’re just the ones we know the best, the ones that feel as familiar and tactile as our own bodies. “Heavy” understands this and pulls no punches in describing their pain. As he says about this memoir, “I wanted to write a lie. You wanted to read that lie. I wrote this to you instead.”

In many ways, “Heavy” is both a dissection of his relationship to his mother and a confession to her of his sins. “Confession,” though, is a funny word here. For a book that’s so Southern and so black in its cultural referents, it’s weird and oddly freeing that the church and Christianity are nearly nonexistent entities in the book. Laymon, instead, evokes the language and rhetorical devices of the Black Panthers, second-wave feminism and 1990s hip-hop, only invoking gospel-like language at the very end, to build toward a sort of manifesto of apocalyptic communal blackness.

In doing so, he comes to terms with his black body in America, his relationship with his mother and his inability to love himself or others. “Heavy” isn’t triumphant or redemptive but instead ambivalent and anxious. It’s passionate in its need to acknowledge that, “there will always be scars on, and in, my body from where you harmed me. You will always have scars on, and in, your body from where we harmed you. You and I have nothing and everything to be ashamed of, but I am no longer ashamed of this heavy black body you helped create.”

Kiese Laymon is talking to his mama, but he’s also talking to America. Maybe they’re the same thing, with the same lacerations, weight, fierce pride and searing pain. In addressing “Heavy” to one particular black woman, Laymon manages to touch on all of the nation’s wounds, his fingers trembling as they poke the bloody gashes, but poking them nevertheless.

NONFICTION

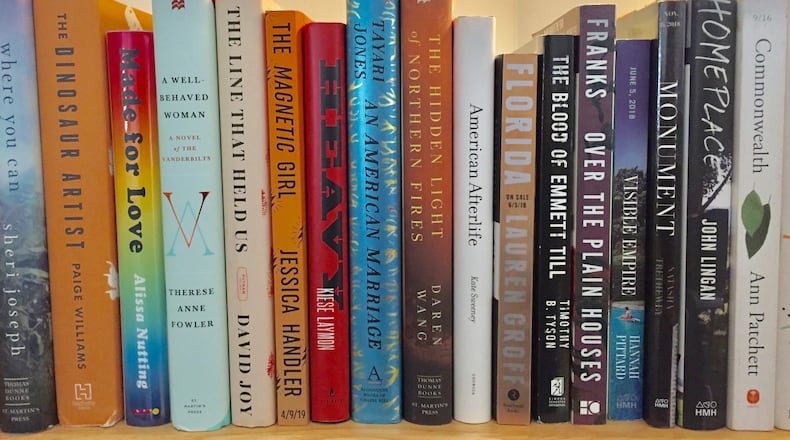

‘Heavy: An American Memoir’

by Kiese Laymon

Scribner

256 pages, $26

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured