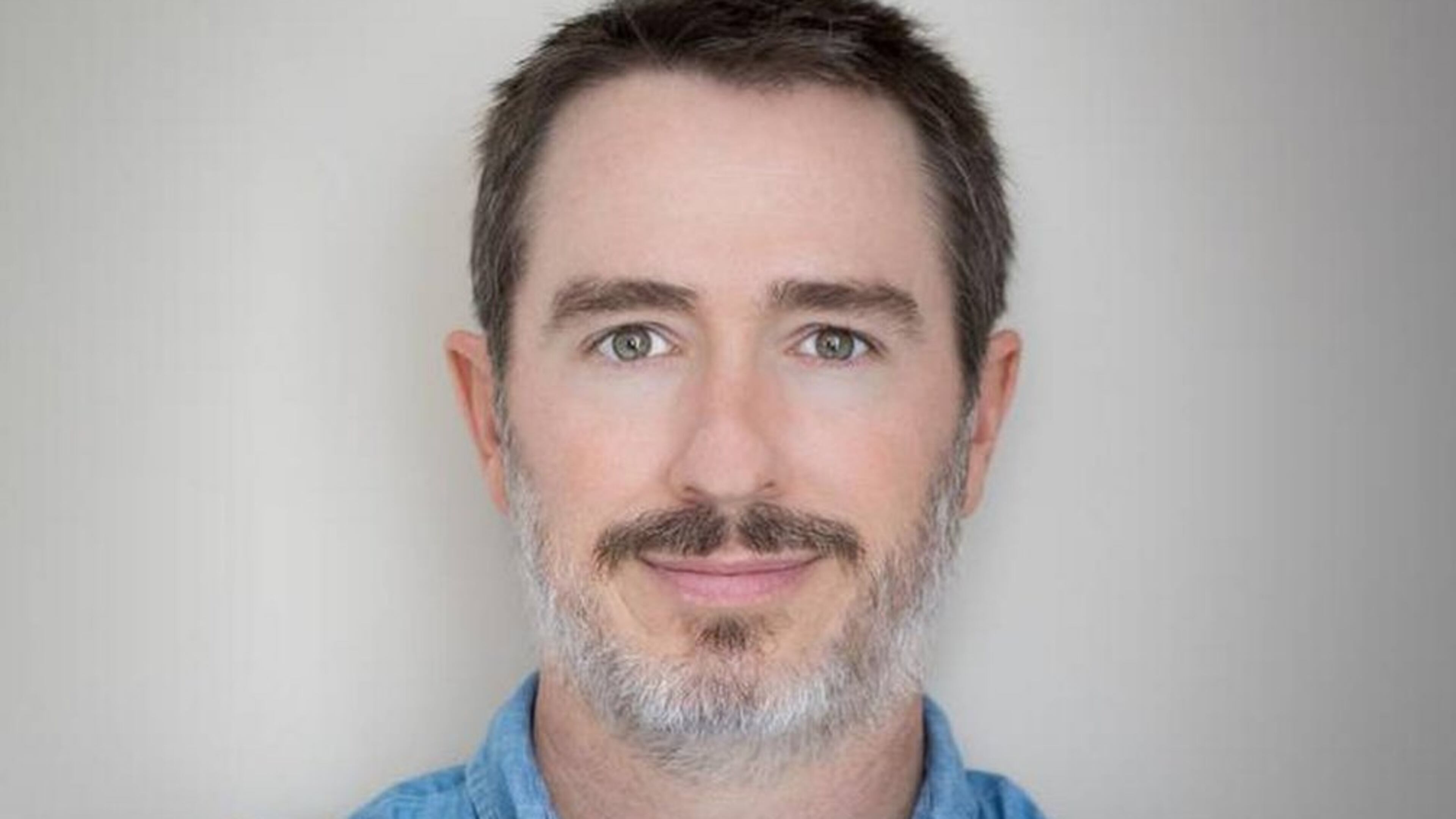

The ink was hardly dry on Wiley Cash’s 2012 debut novel when Vanity Fair dubbed him “the Justin Timberlake of American literature.” It was a joke, obviously — a funny, if misleading, soundbite lifted from a truncated quote.

In truth, Cash had been mistaken, briefly, for the singer during a book event at Timberlake’s New York restaurant. This led to ribbing from colleagues and the author’s cheeky retort that his real goal was to be more like Nicholas Sparks.

But Cash’s latest novel, “The Last Ballad,” shows that the pop star analogy might be somewhat accurate. Like a musician who rolls out different sounds and personas on each new album, Cash keeps experimenting with genre and voice. His first book, “A Land More Kind Than Home,” was a grotesque, Gothic homage to Flannery O’Connor and Dennis Covington. “This Dark Road to Mercy” relied more on tropes from suspense novels, with mixed results.

“The Last Ballad” doesn’t rush to announce its genre, but quickly telegraphs that it’s not just another rural noir potboiler. In lieu of a prologue, a provocative newspaper clipping condemns textile mill workers for striking, calling them “Bolshevists who want to destroy our government.” The novel revisits a famous labor uprising that occurred in Cash’s hometown, Gastonia, North Carolina.

The Loray Mill strike of 1929 escalated into a violent, months-long clash in which the chief of police and a celebrated labor organizer were killed. Though the strike failed, it inspired a slew of social novels in the 1930s, including Sherwood Anderson’s “Beyond Desire.” “The Last Ballad” creates palpable empathy for the strikers, but also attempts to consider class warfare from several sides.

Cash brews up a believable fictional backstory for Ella May Wiggins, a real-life mill worker and balladeer who became the voice of a fledgling labor movement. The first chapter finds bedraggled Ella in hot water for missing a shift at American Mill No. 2, known as the least desirable workplace in the county, thanks to its policy of hiring black and white employees for the same jobs.

At age 28, the struggling mother of four has already endured enough devastation for a lifetime, including a failed marriage and a child’s death. Manning finger-eating thread spindles and earning a whopping $9, she works 70 hours a week on the night shift.

Ella frets over lint in her throat, tar in her lungs and the baby in her belly, but she hasn’t told anyone about the pregnancy. Her shiftless boyfriend, “the kind of man to which nothing good could happen,” warns her against going to a union rally in nearby Gastonia. Ella responds, “Well, I got to believe in something. Might as well believe in the union.”

Although most of the book unfolds in 1929, an abrupt leap to 2005 finds Ella’s daughter Lilly opening up about long-repressed childhood traumas. Cash’s prose is often spellbinding, but this torrent of self-disclosure especially resonates. Lilly confesses that she has spent much of her life wondering “what it means to be on this earth, what it means to leave it, what is left of us behind once we are gone.”

More than just a mouthpiece for eloquent reflection, Lilly delivers stunning disclosures that give the historical novel a hard shove toward the mystery shelf. The category doesn’t really fit. We see hints of the gritty mountain noir that made Cash famous — tar paper shacks, moonshine in Mason jars, religious zealotry — but the crimes this time are less personal, more societal.

Ella gets invited to perform one of her protest anthems for the union rally. Soon enough, she’s the voice of the resistance. Her perseverance, already saint-like, gets tested repeatedly when she witnesses the chaos unfolding in the Loray Mill village: families dragged out of homes; angry mobs blocking streets; policemen dodging rotten cabbages, rocks and bottles.

Cash has a rare talent for using elegiac language to create movement on the page. The book’s pacing, however, begins to stumble before the midpoint due to an overcrowded narrative. Just as the situation in Gastonia is heating up, the author hits pause on the strike and introduces a succession of tangential characters.

Cash’s earlier novels functioned like musical canons, compositions performed by three distinct and complementary voices. “Ballad,” which runs much longer than either of those books, uses similarly varying perspectives but invites way too many personalities on stage.

Over 23 chapters the book jumps between eight different characters. We meet mill owner Richard McAdam and his daughters, Claire and Katherine, as well as Hampton, a railway porter. The saga of hen-pecked Verchel, who takes to the bottle after a work accident, brings unexpected comic relief to the novel’s first half. It later evolves into a more twisted, less believable tale of obsession. Still, Verchel’s story has a lot more life than some of the other subplots.

The structural approach makes sense once the storylines converge, eventually supporting an overarching theme about the need for a community to come together for the sake of the common good. This “it takes a village” message has a bittersweet twinge in “The Last Ballad,” considering the brutal aftermath of the Loray Mill uprising, but feels as timely as ever in light of today’s striking divide between the haves and have-nots.

FICTION

‘The Last Ballad’

By Wiley Cash

William Morrow

384 pages, $27