‘Mama’s Last Hug’ draws parallels between human and ape emotions

For more than 25 years, biologist Frans de Waal has been studying primates at Emory University, where he is director of the Living Links Center for the Advanced Study of Ape and Human Evolution. But all that comes to an end this summer when he retires.

In addition to spending some time traveling with his wife, the 70-year-old Tucker resident will continue to teach part time at Utrecht University in the Netherlands and guest lecture on his topic of expertise: the fascinating parallels between humans and apes.

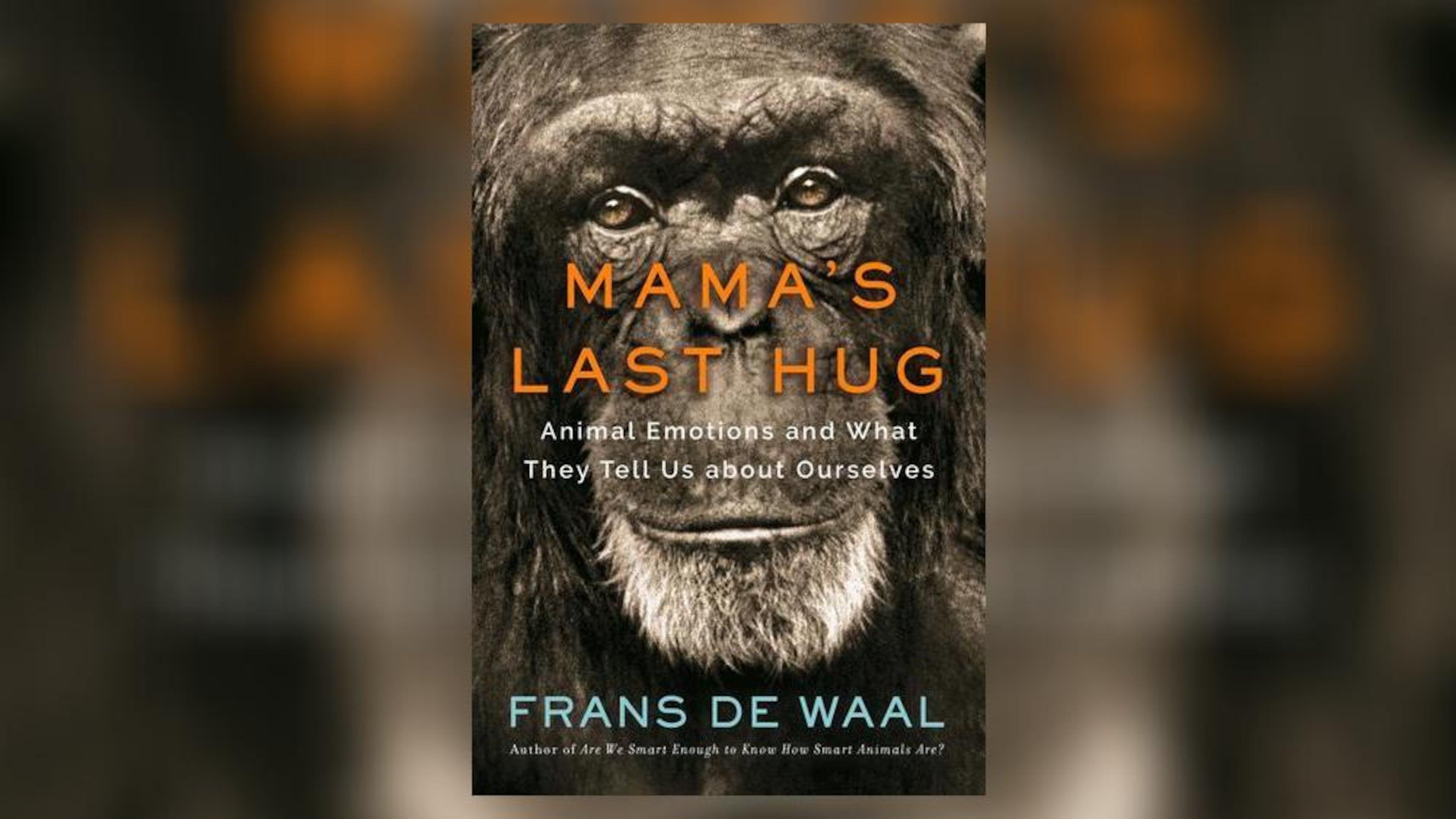

Meanwhile, he is promoting his latest book, "Mama's Last Hug: Animal Emotions and What They Tell Us About Ourselves." It was inspired by a 2016 video that shows the author's colleague, Jan van Hooff, paying a deathbed visit to Mama, a 58-year-old chimpanzee, at Burgers' Zoo in the Netherlands. Mama and van Hooff had worked together for four decades, but they had not seen each other for several years. The video captures the listless chimp lying motionless in the fetal position on a bed of hay. When van Hooff appears in the frame, she is slow to respond, but when she does, she flashes a wide smile and issues gentle coos before reaching out a hand to stroke van Hooff's hair and throw her long arm around his neck for an embrace.

The emotional exchange touched a chord in viewers. The original video has been viewed more than 10 million times to date. And it prompted de Waal to use it as a jumping-off point for his book about how animals express emotions and how similar they are to our own.

AJC: Your book is about much more than the viral video of Mama on her deathbed. Why did you choose that title?

De Waal: When the video came out, many people said they were extremely moved, which I fully understand. I was very moved by it. But also, many people said they were surprised by how humanlike the emotions of a chimpanzee are. I was surprised by that. We know that we are the closest relatives to chimpanzees, and the other way around, so we shouldn't be surprised. That's why I took it as the title. I (decided to) explain all these facial expressions because people may not know that animals have them. They're just the exact same things we do with our faces.

AJC: You say a smile is a complex facial expression in both humans and apes, that it’s not always an indication of happiness. Can you elaborate?

De Waal: Sometimes when we do these tests on humans, we present them with a whole bunch of pictures of facial expressions and we have very simple labels. For the smile, it would be happiness or sadness. And, of course, you choose happiness when you look at the smile. But these simple labels, I don't think they cover very well what the facial expression indicates. Because a smile can also be nervous or a way of appeasing others. Laughing is also a sign of happiness for many people, but laughter can be aggressive.

In the book, I talk about where the smile comes from (starting with) teeth baring that we see in macaques, which is usually (a sign of) submission. Then it moves to more appeasing behavior in the apes. When apes bare their teeth, it’s more like humans because it’s a sign of nonhostility. And then in humans, it includes all of that because we sometimes smile when we’re nervous and we smile when we’re nonhostile, but it also gets to friendly and even happy components. So, in humans, it’s an even broader scale of things. A smile is a very complex facial expression, and the simple labels we attach to it like happy or sad really do not cover it.

AJC: Charles Darwin first introduced the concept of animal emotions back in 1872, but those theories are still criticized today by some scientists. You call this resistance anthropodenial, a “desire to set humans apart and deny our animality.” What is the motivation for that denial?

De Waal: I invented that term because we very often get criticized for anthropomorphism (the attribution of human characteristics to animals). That was the usual weapon of the behaviorists as soon as you proposed, let's say, my dog is jealous, even though everyone who has a dog knows they can get jealous. You were not allowed to use that terminology. That's why I invented the term, because I think it's actually a bigger problem to deny there are similarities between humans and animals, especially when it comes to the apes because the similarities are so obvious. That would be like calling the hand of a chimpanzee a front paw, for example. You give it a different name, but it still has the same structure and it's still the same sort of hand as we have. The tendency existed in science, more than in the general public. The general public is less reluctant to attribute emotions to animals than the scientists.

AJC: You identify a lot of bias in the terminology the scientific community uses when referring to animal emotions. For instance, chimpanzees are described as displaying “laugh-like behavior” and fear in rats is called “survival circuits.” Do you see that changing?

De Waal: Scientists over the last century have been very reluctant to talk about emotions. This was the effect of behaviorism. They didn't accept it for humans in the beginning either. We were only supposed to look at behavior. That's why they were called behaviorists.

For humans, the taboo was broken in the 1960s with the cognitive revolution in psychology, and what the behaviorists did was, they doubled down on animals. They said, well OK, maybe humans have internal states. That’s a useful concept. But for animals, we’re not going to do that, so we have lived under that taboo of not talking about animal emotions and animal mental capacities. That is now finally being lifted. At this moment, it’s really now disappearing. There is a whole generation of younger scientists who are starting to ignore all those taboos that we got imposed on us.

AJC: Another bias you identify in the science community is the resistance to acknowledging human hierarchies and the power dynamic. What is the root of that resistance?

De Waal: We like to be egalitarians, especially liberals in America. Certainly, in the universities. All these professors, they love to be egalitarian. Although if you go to faculty meetings, it's very obvious there are power struggles going on between all these egalitarians. I think there's an enormous amount of hypocrisy going on. We have hierarchies. We have status. We have power struggles, but we act as if we don't. We act as if power is a dirty word, which it really isn't, in my opinion. Each time I get a new social psychology textbook in my hands, I look at what they say about power and dominance, and they almost don't say anything. It's as if human society exists without that. It's one of the biggest taboos that we have. We are in massive denial about how power hungry as a species we are.

AJC: NPR gave your new book a favorable review, but you were criticized for gender stereotyping in the chapter on power when you said, “Attractive women, especially those of childbearing age, are perceived as rivals by other women.” Can you respond to that?

De Waal: I'm not sure that the observation that women can be competitive is necessarily gender stereotyping. I don't know what purpose it serves to present women as all loving each other and hugging each other and getting along fine. I mean we all know that is not necessarily the case. When I speak to people in the business world, you always hear there's quite a bit of competition among women. And women are not always helpful to one another. It's better to face the reality that men can be very competitive. Yes, we know that. And women can be, too.

AJC: You draw a lot of parallels between humans and apes when it comes to politics. You describe President Donald Trump as “strutting like a male chimp on steroids” during his presidential campaign, but you say he does not meet the requirements of a true alpha male. Explain.

De Waal:An alpha male officially is defined as the highest-ranking male, that's all it is. But the characteristics of an alpha male are not that he is just the most dominant. He also keeps peace in the group, and he interrupts fights and he's very impartial when he does so. He is the consoler in chief. The alpha male is more than just being a boss and having privileges. There are certain obligations that come with it. I think Trump qualifies in the climb to the top by using intimidation and being a bully, which is the traditional way also with chimpanzees. That's the way you get to the top. But then once you are there, you have to be a unifier. That's what alpha males do. They bring the group together. That is the part that is missing, I think.