A literary friendship and the Harlem Renaissance

By faulting his two subjects equally and refusing to pick sides, author Yuval Taylor presents a compelling, evenhanded account of the literary feud between celebrated African-American writers Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes, a split often cited as the death knell of the Harlem Renaissance, of which they were key players.

"Zora and Langston" is a fascinating and lively story of two iconoclastic writers whose shared passion for creating work that disrupted literary conventions was complicated by the controlling influence of a wealthy white patron, the presence of an attractive, young typist and a collaborative project that turned sour.

Initially called the Negro Renaissance because its influences exceeded the boundaries of Harlem, the explosive era of black artistic, intellectual and social expression in the 1920s is vividly portrayed as a time of unbridled creativity and freedom when the social constructs that separated people by race, class and sexual identity had grown porous. The landscape was fertile for new ideas when Hurston and Hughes first met at a literary awards dinner in 1925 where she won a prize for her story “Spunk,” and he won a prize for his poem “The Weary Blues.”

A chance encounter in Mobile, Alabama, during the summer of 1927 sealed the bond of their friendship. Hurston was in town researching Cudjo Lewis, believed to be the last living former slave in the U.S. (The book, "Barracoon," wouldn't be published until 2018.) Hughes was touring the South making public appearances and conducting research of his own. Together they decided to tour the region in Hurston's Nash coupe. In Georgia, they attended "backwoods church entertainment given by a magician" in Fort Valley, consulted with a 103-year-old root doctor in Savannah and saw Bessie Smith perform in Macon.

In a postcard to an associate back home, Hurston wrote: “We are being fed on watermelon, chicken and the company of good things. Wish you were with us. Lovely people not spoiled by soap-suds and talcum.”

On the surface, the writers were quite different. Hughes was a decade younger, although Hurston usually lied about her age. He came from Lawrence, Kansas, and she was from the rural South — born in Alabama and raised in Florida. He was reserved and intense; she was flamboyant and expressive. But their work shared a similar sensibility.

Both authors deemed the highbrow content and intellectual tone in vogue among black, middle-class writers as representing a Caucasian perspective they eschewed. Despite the fact they were both college-educated (at Barnard and Lincoln, respectively), Hurston and Hughes took their inspiration from “Negro folktales,” blues musicians, chain-gang members, dancers and gamblers. They wrote about plain folk who spoke in dialect. The black literary establishment was critical, but New York’s wealthy white society was charmed — not only by their literary output, but by their ability to liven up a cocktail party, especially Hurston, who drew attention with her colorful outfits and ribald storytelling.

Another thing Hurston and Hughes shared in common was their poverty. That changed when they were introduced to Charlotte Osgood Mason, a wealthy socialite nicknamed Godmother. Described as a sweet, soft-spoken, elderly woman with a deep interest in primitivism, she became a patron to Hughes and Hurston, providing them with monthly stipends for years. In Taylor’s hands, Mason comes across as something of a Svengali who holds a mysterious sway over her beneficiaries. They all exchanged effusive letters professing love and devotion to one another that bordered on the fanatical. But when Mason tried to exert control over their work, her beneficiaries started to chafe.

After their summer sojourn, the writers saw little of each other for three years, but they corresponded often as their writing careers blossomed. Although Mason lost half her fortune in the stock market crash of 1929, she continued to support her beneficiaries. By the end of that year, both Hughes and Hurston found themselves living two blocks apart in Westfield, New Jersey.

The fractures in their friendship started to appear when Godmother hired Louise Thompson, a young college graduate, to provide secretarial services for Hurston and Hughes. Citing multiple sources, Taylor asserts that Hurston became jealous when Thompson and Hughes grew close. Meanwhile, Hurston and Hughes began collaborating on a play called “Mule Bone,” based on a “Negro folktale” Hurston often told at parties. Mason was not pleased. She considered theater to be a vulgar pursuit and not worthy of her beneficiaries’ talents. Besides, she was keen to see Hurston complete her manuscript on folktales.

To alleviate the tension, Hughes proposed Mason quit paying him and “simply let me retain (your) friendship and good will that had been so dear to me.” Instead, Mason “exploded in fury.”

Without explanation, Hurston moved backed to Manhattan, where she began to work in earnest on the manuscript. “It was quite clearly in her best interest to distance herself from Langston at this point if she wanted to remain in Mason’s graces,” writes Taylor.

The final break between Hughes and Hurston came when he pursued a staging of “Mule Bone” with a small community theater company in Philadelphia without first consulting Hurston. A legal battle over ownership and creative control ensued, complete with competing copyrighted scripts. The play would not receive its first staging until 1991, long after the authors’ deaths.

Despite the flowery letters Hurston, Hughes and Mason exchanged, and the alleged jealousy Hurston felt toward Thompson, all of their relationships were platonic, writes Taylor.

“It’s difficult these days, when love and sex are so intertwined, to imagine a world like that in which the protagonists of this book lived. … (S)exual desire was rarely part of the equation.” Nevertheless, writes Taylor, they shared “the kind of intense feeling that unbalances one’s emotions and that, when brought to an end, can produce anxiety and depression.”

Hurston and Hughes would never mend their rift. Instead, they each tried to get the last word in their autobiographies. Hughes devoted six pages in “The Big Sea” to Hurston, painting a condescending portrait: “She was always getting scholarships and things from wealthy white people, some of whom simply paid her just to sit around and represent the Negro race for them, she did it in such a racy fashion.”

In “Dust Tracks on a Road,” Hurston took a different tack. As Taylor observes, she “mentioned Langston only once, in passing …”

NONFICTION

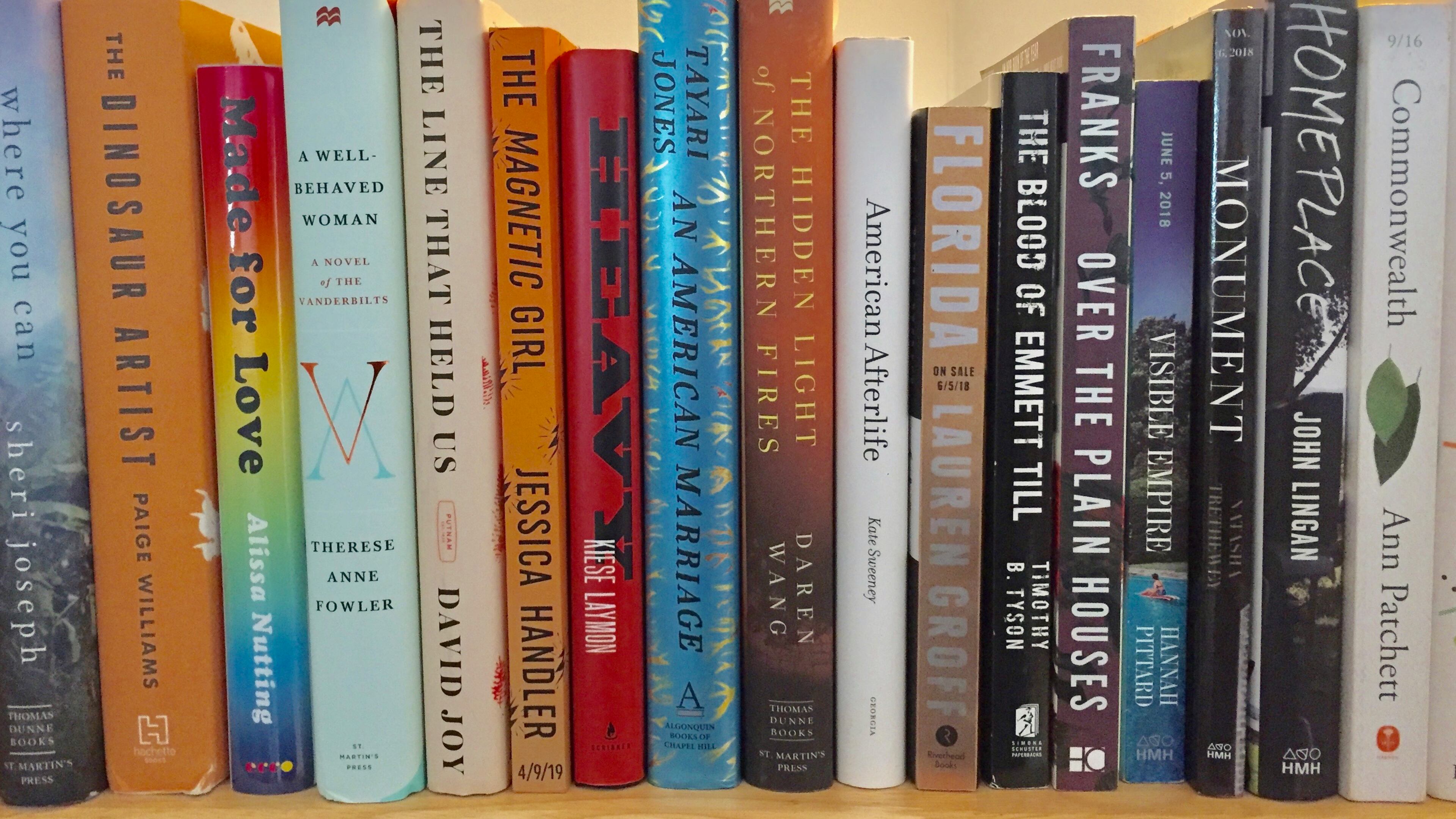

“Zora and Langston”

By Yuval Taylor

W.W. Norton & Company

304 pages, $27.95