A giant gets his due

In spring 1977, Romare Bearden’s “Odysseus Series” opened at the Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery in New York’s Upper East Side. Bearden, already considered a major presence in American art, used collage to reinterpret the classical myth of the wandering hero through the lens of the black diaspora.

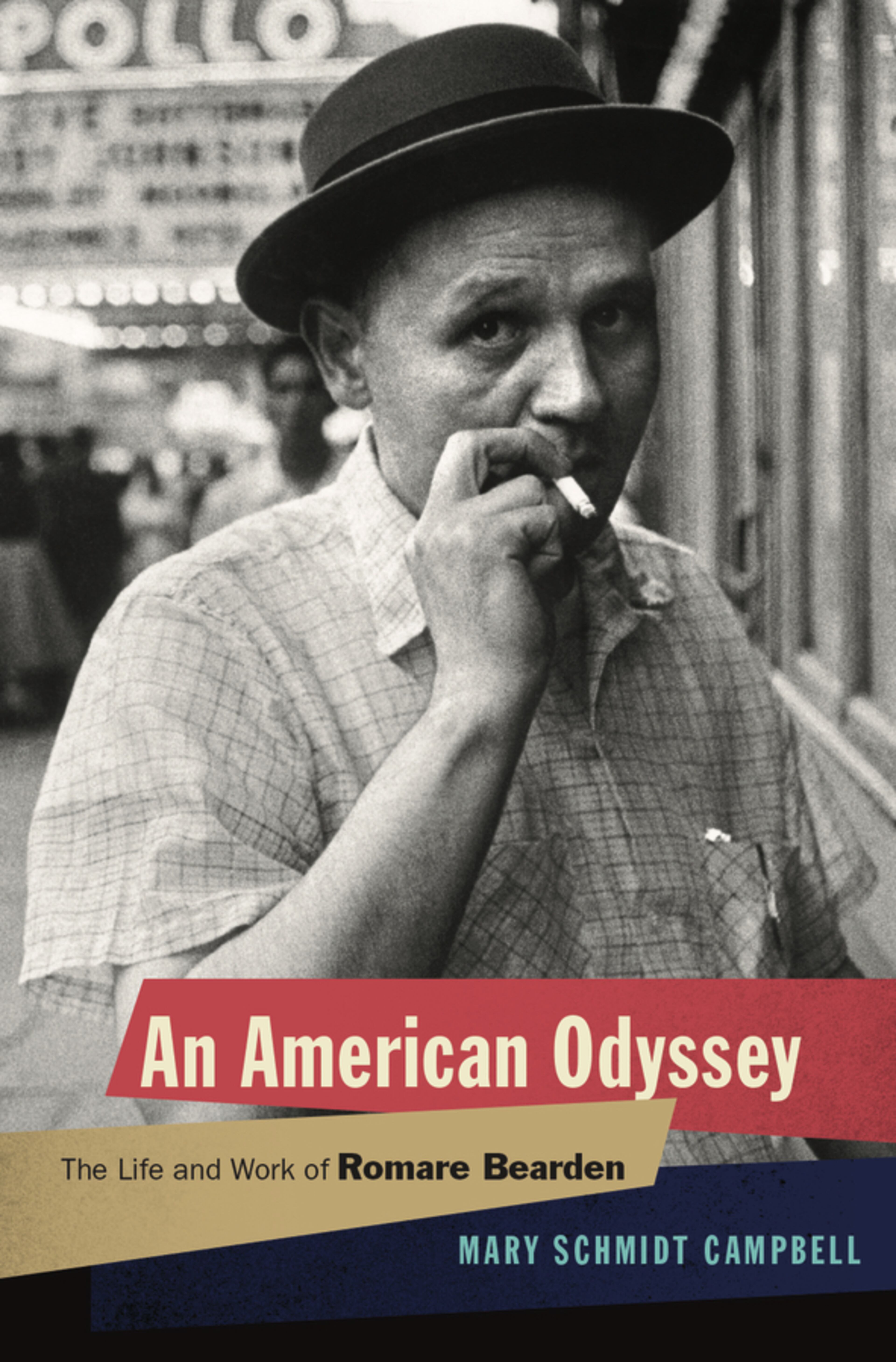

In “An American Odyssey: The Life and Work of Romare Bearden” (Oxford University Press), Mary Schmidt Campbell adapts the same myth to compellingly tell the story of one of the most important artists of the 20th century.

Known best in Atlanta as the president of Spelman College, Campbell struck up a correspondence with Bearden in the early ‘70s when she was a graduate student at Syracuse University. He, in turn, took an interest in her career, and their professional relationship would continue until his death in 1988. It was on his recommendation that she took the position of executive director of the Studio Museum of Harlem, and it is through her own expertise in the history of the arts and culture of Harlem that she opens a window into his life.

Bearden was born too late to be a full-fledged member of the legendary Harlem Renaissance, but through his mother, he grew up immersed in that rich world of thought and creativity. Activist, actor, occasional model and New York social correspondent for the Chicago Defender, Bessye Bearden was a type of social nexus for that period of artistic flowering. Through the parties she threw at her 131st Street apartment, her teenage son met such giants as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and Paul Robeson. The strength of Bessye’s presence would manifest years later in the artist’s portrayal of powerful women in his collages.

Romare’s father, Howard, makes less of an impression. A dining car waiter for the Atlantic Coast Rail Line, his work and his quieter personality kept him out of the limelight in which Bessye thrived.

As rich as that Harlem culture was, other periods of Bearden’s childhood would also serve as fuel for his artistic vision. Long stretches in his maternal grandparent’s boarding house in Pittsburgh, and occasional summers with his patrician grandparents in Charlotte, N.C., served as a type of survey of the black experience in the rest of America. In both of those places, young Romie roved beyond the safety of his grandparents’ homes. In Charlotte, he followed a young schoolmate to work a day in the cotton fields, and in Pittsburgh, he spent his days delivering ice slabs door-to-door or visiting his young friend Eugene Bailey in his room in a nearby brothel. In the evenings, he had dinner with the boarders who worked at the nearby steel mill.

A surprising thread that runs through Bearden’s youth is his baseball career. Starting in the Harlem sandlots, continuing through his time playing with the Boston University Tigers and local negro leagues, and culminating with an offer from legendary Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack. Decades before Jackie Robinson would break the color line, the light-skinned Bearden was told he could play in the major leagues if he was willing to pass for white. He declined.

A sense of creative roaming threads through Bearden’s life. He reinvents himself, again and again, through cartoons, watercolors, oil, writing, songwriting and, eventually, collage.

Bearden’s development as an artist is tracked through his exhibits, announcements and reviews, but it is in the stories of the swirl of people around him that the writing comes alive.

The book is exhaustively researched, but those scholarly chops sometime make for passages that read slow to anyone but the most ardent Bearden scholar. There are references to Bearden’s extensive journals and personal writings, but we see little of the content, and we long for a peak behind that curtain. There are times when Campbell struggles to tell a compelling story while also creating the kind of resource for scholars for years to come.

The pages are most vivid when Campbell explores the inspiration for specific pieces, as when she tells how Eugene Bailey’s early death lead half a century later to the piece “The sporting people were allowed to come but they had to stand on the far right,” or how his first recorded collage, “Land Beyond the River,” was a gift for a playwright friend on the success of his play by the same name. Those moments are the most engrossing, engendering a need to seek out the artwork and take it in first-hand.

Harlem during its heyday, an artist’s studio above the Apollo Theatre, a postwar stint socializing with James Baldwin and Richard Wright in the cafes of Paris — Bearden was a kind of woke Forrest Gump who surrounded himself with a panoply of the most important figures of 20th century culture. But in the era of the tell-all exposé, we get the story of an artistic titan who managed to avoid the worst pitfalls associated with the artistic lifestyle. He and his wife Nanette shared a long, happy marriage, and her guidance steered him through a fairly trivial encounter with substance abuse.

In her introduction, Campbell places Bearden in a progression of thought leaders highlighted by such events starting with Frederick Douglass’ 1861 lecture series Pictures and Progress through W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1900 Paris World’s Fair “American Negro” photography exhibit. Bearden’s work, like those who came before him, was often focused on recovering the image of blacks in America from the crude and cruel caricatures of the 19th century Harper’s Weekly and Puck to that of a prosperous and vital component of American life. “An American Odyssey” makes the argument that not only does Bearden’s work accomplish that, but the rich life he led does as well.

NONFICTION

‘An American Odyssey: The Life and Work of Romare Bearden’

By Mary Schmidt Campbell

Oxford University Press

464 pages, $34.95