Allison Moorer explores violent past in ‘Blood’

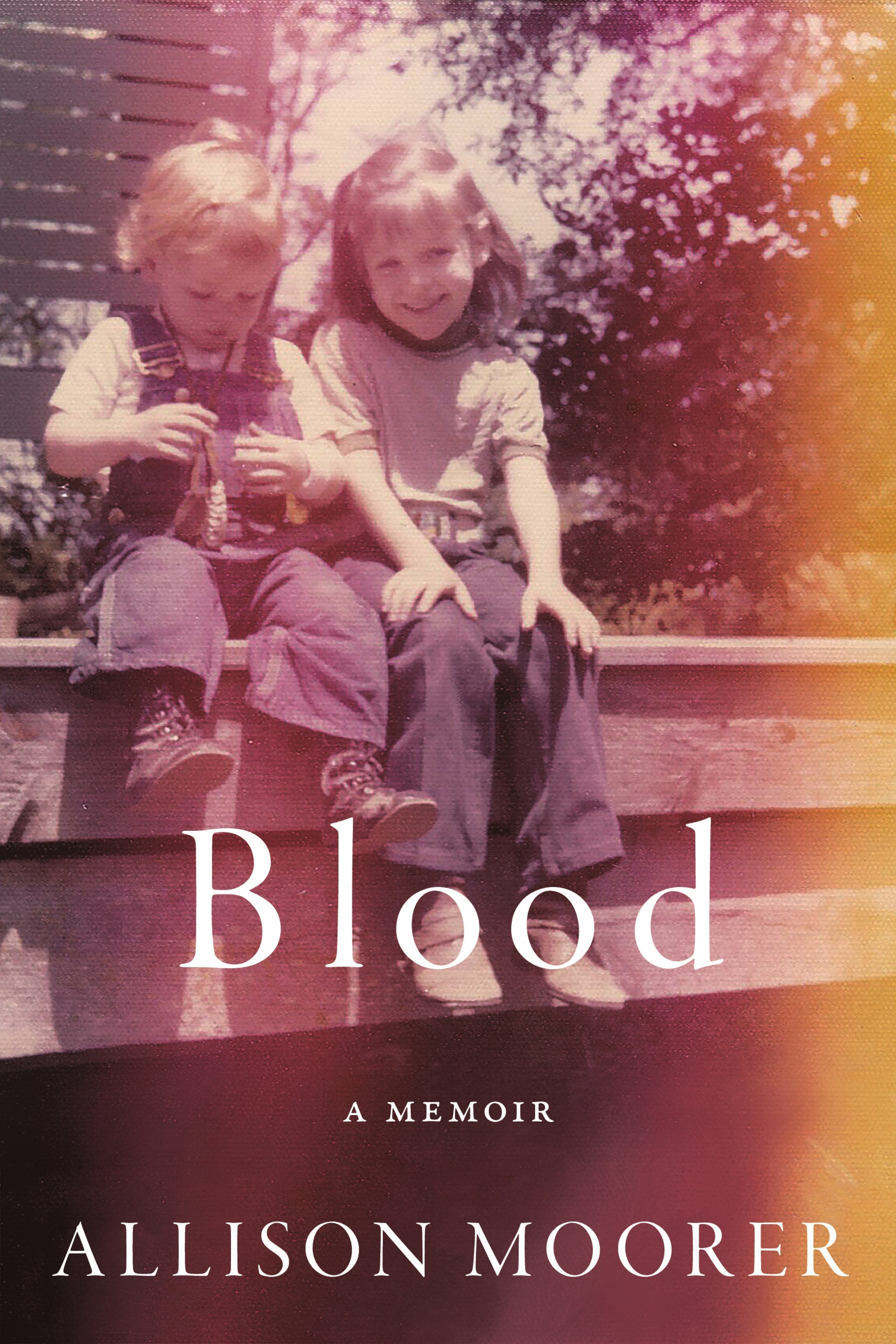

With the voice of an angel and a face to match, singer-songwriter Allison Moorer is a captivating performer, especially when she sings with her sister, Grammy Award winner Shelby Lynne. Their chill-inducing harmonies were honed from birth, an aural manifestation of the sisterly bond that sustained them through their horrific childhood, much of it spent cowering in fear from their rage-filled father. Their terror ended early one summer morning in 1986. While his teenage daughters slept inside their Alabama home, their father killed their mother with a shotgun blast, and then he killed himself.

Moorer recounts those events in her literary debut, "Blood," an outlier in the realm of celebrity memoirs. It is beautifully crafted, often poetic and was written without benefit of a ghostwriter. (Moorer holds a master's of fine arts degree in creative writing from The New School.) And it's less about Moorer than it is about her parents. In fact, you could fill a book with what Moorer leaves out of "Blood."

She barely touches on her music career, omitting a reference to her 1999 Oscar nomination for her debut single, “A Soft Place to Fall,” featured in the Robert Redford movie “The Horse Whisperer.” It contains no mention of her 10-year marriage to country artist Steve Earle. And her current husband, singer-songwriter Hayes Carll, identified as “H,” is only mentioned in passing.

Instead, "Blood" focuses squarely on Moorer's parents and her efforts to piece together shreds of memories and facts in order to help her understand just who Vernon Franklin Moorer and Laura Lynn Smith Moorer were, and how their contentious union led to such a devastating end.

The couple met in Jackson, Alabama, where he was a high school teacher and she was a secretary. He had musical aspirations; she had a beautiful voice. By the time they married in 1968, Shelby was on the way. Playing records and singing together were common pastimes for the whole family. They called the living room the music room because it contained a record player, a piano, guitars and amps. But he couldn’t keep a job and was never without an avocado green tumbler filled with Jim Beam and water. Worst of all, he was mean and violent, and he vented his mounting frustrations mostly on his wife.

“He didn’t like women who spoke too much or showed an excess of personality. He didn’t like competition. Everyone loved her. So he shrank her. He shrank her until she almost disappeared. She decided that she didn’t want to disappear anymore. Then he disappeared her for good.”

Moorer’s protector was big sister Shelby, aka “Sissy.” Her musical talent was apparent early on. She often joined her parents on stage at local bars to perform, triggering her father’s ire when audiences wanted to hear her more than him. Fearless and defiant, she challenged her father’s mistreatment of the family, and he responded by bloodying her face with his fists. Mother and daughters often fled to the safety of a relative’s house, but they eventually returned, until the time they didn’t. That time their mother rented a house just for the three of them. That time was different, and he knew it.

“Blood” begins with Moorer’s memory of her parents’ deaths told from her child’s-eye view. What follows is a collage of memories, official reports, other people’s accounts and interstitial poems, vignettes and reveries that paint a multilayered picture of the family’s history of dashed hopes and torment. There are accounts of a globe light fixture hurled through a kitchen window and dogs nearly beaten to death, juxtaposed with sweet riffs on the contents of her father’s briefcase and a list of her mother’s made-up words, followed by the emotional punch of a proclamation titled “What Happens When You Hit Your Daughter.”

Among the quest for answers that fuels Moorer’s narrative is whether the murder-suicide was premeditated or an act of impulse. Even more vexing, why did police find three spent shotgun shells when Moorer heard only two shots? Did one shot fail? If so, was it before the shot that killed her mother, or the one that killed her father? What were their thoughts in those final moments? The details of the last few seconds of her parents’ lives grow potent with meaning for Moorer.

“Blood” dwells mostly in the past, but near the book’s end, Moorer leaps to the present with a scene of the sisters performing a duet at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame at an Everly Brothers tribute. It suggests a kind of healing that surpasses anything words alone could achieve. “The sounds of our voices blending as only those that belong to siblings can buzzed through (the audience) just as it did us. Our voices are like two halves of a whole, and when we sing together we make one thing.”

She also introduces someone who has given her life new purpose, 9-year-old son John Henry.

The implication is that music and family continue to sustain her, as they did in her youth. Together they provide solace as Moorer comes to terms with the realization that some questions about her family’s past will never be answered.

NONFICTION

By Allison Moorer

Da Capo

320 pages, $27