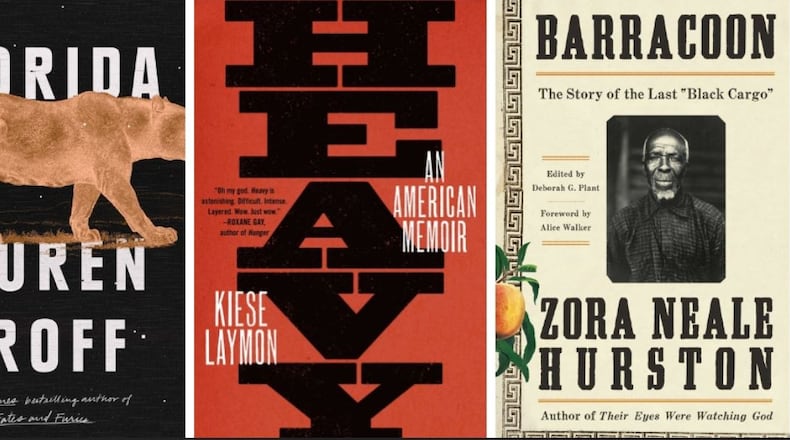

Is it just me, or was 2018 a particularly outstanding year for Southern books? From Kiese Laymon’s incendiary memoir “Heavy” to the posthumous publishing sensation of Zora Neale Hurston’s “Barracoon” to Lauren Groff’s National Book Award finalist “Florida,” the books this year displayed a range of subjects and forms that were richly varied. Here are 11 of our favorite Southern books of the year.

Elsie is a teenage waitress at the Betsy Ross Diner in 1996 Waterbury, Conn. She falls in love with the line cook, Bashkim, a political refugee who left a wife behind in Albania. In the throes of “an epic sort of love you get tattooed across your forearm without thinking twice about it,” Elsie and Bashkim share a dream of escaping “maybe the crappiest place on earth” for a new life in Manhattan. The storyline in this debut novel by Athens author Xhenet Aliu alternates with another storyline set 17 years later, told from the perspective of the couple’s teenage daughter, Luljeta, “the latest in a long line of fatherless daughters.” Luljeta also wants to escape Waterbury, but first she goes on a quest to find the father she never knew. “Aliu’s writing is so vivid and invigoratingly unadulterated,” writes AJC book critic Becca J. G. Godwin. “There’s no fetishizing the human experience in this tale, and that’s what makes it shine.” (Random House)

Long-listed for the National Book Award, Tayari Jones’ novel examines what happens to a marriage when partners are forced to live separately. Ambitious sales rep Roy Hamilton and artist Celestial Davenport encounter the usual challenges typical of newlyweds. But when Roy is falsely accused of a crime and sent to prison for 12 years, the couple must forge a relationship apart. Through an exchange of letters, they grapple with their guilt and regrets over past and present transgressions, as well as the strain that mounts over the tension between his incarceration and her freedom. Jones “remains laser-focused on the gradual loss of trust in their relationship, the trauma that outlives a sentence served, and the nuances of guilt when one-half of a couple loses his freedom, while the other half lives it out loud,” writes AJC book critic Anjali Enjeti. (Algonquin)

Charles Frazier creates a vivid portrayal of Varina Davis, the First Lady of the Confederacy by virtue of her unhappy marriage to Jefferson Davis. Addicted to morphine and bereaved over the death of her children, she is portrayed as a complex woman who is disdainful of the South and its Lost Cause. Nevertheless, she cannot bring herself to disavow slavery, even when pressed near the end of her life by a former slave named James. His interviews with the aging, ailing woman, conducted over a series of Sundays, create the structure for the telling of her life story, including her daring attempt to escape Union forces via horse-drawn carriage, with children and slaves in tow. “If Frazier succeeds in finding a place for Varina Davis in the popular mind, he raises, through James’ interrogations, the issue of her complicity with evil — her fatal choice, as it were,” writes AJC book critic Jeff Calder. “She is exceedingly humane, though she never seems to reconcile the contradictory feelings she has about Southern slavery.” (HarperCollins)

Chris Offutt’s second novel chronicles the travails of a Korean War vet named Tucker, beginning with his return home to the hill country of east Kentucky in 1954 and spanning two decades. Tucker is a man most at home deep in the woods, far away from towns where there are “too many people doing too many things at once.” He marries a woman after saving her from the lecherous clutches of her uncle, and they produce five children, most of whom suffer birth defects. He supports his family by running moonshine and along the way makes questionable decisions that catapult the precarious life he’s patched together into turmoil. The saving grace of this dark entry in the canon of Appalachian noir is the deep level of humanity Offutt brings to his taut tale. (Grove Press)

Zora Neale Hurston first submitted this nonfiction book for publication in 1931, but her publisher refused to print it. At issue was her use of dialect reproduced verbatim from her recordings with her subject, Oluale Kossula, the last survivor of the last ship to transport slaves from Africa to the U.S. Hurston first met Kossula, then 86, in 1927 in Africatown, a community Kossula and some of his fellow West Africans established in Plateau, Ala. She returned four years later to get his full story, which unfolds within the pages of “Barracoon” in his own mellifluous voice. About the day his African village was captured by slave traders, he recalled: “I see de people gittee kill so fast! De old ones dey try run ‘way from de house but dey dead by de door, and de women soldiers got dey head. Oh, Lor’!” (HarperCollins)

Lauren Groff continues to astonish with the clean, crisp poetry of her prose and the compassion she brings to her closely examined stories about uniquely flawed characters whose actions — or inactions — can break a reader’s heart. A finalist for the National Book Award, this collection has 11 previously published short stories that are set not on Florida’s sunny shores or in theme parks, but in the swamps, prairies, suburbs and remote islands of its backwoods. The stories are told primarily from the perspective of women and children who are haunted in one way or another by boogeymen that take various forms, from alligators, snakes and hurricanes to ghosts, bad husbands and negligent mothers. But perhaps the biggest boogeyman of all is the pervading one-two punch of anxiety and isolation that infuses the collection. (Penguin)

Beth Macy’s hard-hitting investigation into the ravages of opioid addiction in central Appalachia includes sobering profiles of folks like Tess, a young poet who spirals into prostitution to support her drug habit; ATF agent Bill Metcalf, who tracks a kingpin “commuter-dealer” transporting heroin in Pringles cans along I-81; and Dr. Art Van Zee, who, in the early 1990s, urged OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma to scale back its aggressive marketing and reformulate the drug to make it less addictive. The company finally acquiesced 20 years later, but by then, the damage was done. “Until we understand how we reached this place,” writes Macy, “America will remain a country where getting addicted is far easier than securing treatment.” (Little, Brown and Company)

RELATED: Former high school quarterback overdosed— and lived to tell his story

A dark tale about fraternal loyalty and vengeance set against a backdrop of rural gentrification in the Appalachian mountains of North Carolina, David Joy’s second novel draws a sharp line between the haves and the have-nots and illustrates just how deep the tenets of bro code can run. When Darl Moody accidentally kills Sissy Brewer in a hunting accident, he enlists his ride-or-die friend Calvin to help hide the body, triggering a blaze of destruction meted out by Sissy’s brutish brother Dwayne, one of the most vivid literary antagonists to leap from the page since Pat Conroy’s Callanwolde in “The Prince of Tides.” Writes Joy, “In the old days, getting in a bar fight was as simple as stepping on somebody’s boot. Now he had to egg it on all night for someone to shove him. Dwayne wanted to find a group of cologne-soaked frat boys with parted hair and dress shirts and he wanted to break one of those pretty-boy faces simply to see him bleed.” (G.P. Putnam’s Sons)

The residents of the one-horse east Texas town of Kiser don’t know what hits them when debris from the Columbia shuttle disaster rains down one winter day in 2003. But the tragedy proves to be a catalyst in the lives of those who populate this collection of linked stories by Kathryn Schwille. During the recovery process, buried secrets rise to the surface, dreams take flight and sad realities come into sharp focus. “The gruesome carnage that embeds itself in bales of hay, in briar patches and schoolyards, forces this quiet community to grapple with its newfound national attention and reckon with uncomfortable truths,” writes AJC book critic Anjali Enjeti. (Hub City)

The complicated love story between British author C.S. Lewis and American writer Joy Davidman has been told multiple times in books and movies, but always from the perspective of the more famous of the two, the author of “The Chronicles of Narnia.” But in Patti Callahan’s captivating historical novel, the story is told from Davidman’s point of view, which brings fresh insight to the story of their long-distance, slow-burning and socially frowned upon coupling. (HarperCollins)

Penned by Kiese Laymon as a letter to his abusive mother, this searing coming-of-age memoir captures the heartbreaking trials of growing up poor, black and obese in Jackson, Miss. Although Laymon eventually escapes his dire home life to gain an education and become an English professor at the University of Mississippi, not to mention a rising literary star, “Heavy” is not redemptive or triumphant. Writes AJC book critic Walter Biggins, “In many ways, ‘Heavy’ is both a dissection of his relationship to his mother and a confession to her of his sins.” (Scribner)

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured