In the South, by the 1960s, 90 percent of African-American women in the workforce were domestics, according to research by the University of Louisville. Similarly, during South African apartheid, which lasted from 1948 to 1992, black women who were once secretaries, artisans and nurses were relegated to domestic work. These women were expected to labor tirelessly in silence, cooking, cleaning and raising other people’s children. At the end of their lives, there were no monuments erected in their honor or evidence of the vibrant spirits within them, until now. Self-defined visual activist and photographer Zanele Muholi, whose mother worked as a domestic in South Africa, wanted to do something to honor her and other black women whose sense of pride was stripped from them as a result of inequity.

Starting in 2012, Muholi began traveling the world taking self-portraits and illuminating dark skin with the mission of giving voice to the voiceless. It is a common thread in Muholi's work. The artist also co-founded the Forum for the Empowerment of Women, a black lesbian organization in South Africa dedicated to providing a safe space for women to meet and organize. Muholi's resulting photo series, "Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness," opened at Autograph in London last summer and made its U.S. debut at the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, where it is on view through Dec. 8.

On a September afternoon, Muholi, who uses the pronouns they, their and them, walked through the Spelman Museum to check on the progress of the exhibition installation. Their countenance was stern and stature petite, though it’s certain their presence could fill a room, even if it they were not surrounded by nearly 90 photographs of themselves. Muholi, 46, who was born in Umlazi, Durban, and lives in Johannesburg, studied advanced photography at the Market Photo Workshop in Newtown, Johannesburg, and in 2009 earned an MFA in documentary media from Ryerson University, Toronto. Their images have been displayed everywhere from the Brooklyn Museum to the Tate Modern, and were chosen to represent South Africa at the Venice Biennale. Muholi spent much of their career taking photos of others, documenting the LGBT community in South Africa, but for “Somnyama Ngonyama” they turned the camera around.

In place of a catalogue, the show is accompanied by a newspaper-style publication containing images, essays and an interview between artist and curator available for $7 at the museum shop. (A coffee table book containing the images was published by Aperture last month.) In it Muholi says, "I wanted to use my face so that people will always remember just how important our black faces are, when confronted by them. For this black face to be recognized as belonging to a sensible, thinking being in their own right. Remember that when you violate a person … it all starts with the face. It's usually the face that disturbs the perpetrator, which then leads to something else."

Wearing a short-sleeved denim button-down shirt with jeans and a fedora sitting atop their locks, Muholi pointed at each image and relayed the experiences that led to each one.

“Somnyama” means darkness and “Ngonyama” means lioness, which is Muholi’s mother’s clan name in Zulu. South Africa has 11 official languages, of which Zulu is one, and all of the image titles are written in their native tongue. The photographs were taken from Amsterdam to Tokyo, and reflect an experience or sentiment Muholi had in that place. One image was taken while they visited Atlanta for the High Museum’s “Making Africa” exhibition last year. It features a chain around Muholi’s neck and spools of rope in their hair. They saw the objects being used as Halloween decorations in the home of an acquaintance, but they reminded them of slavery, and caused them to consider how objects hold different meanings for different people.

“I wonder if people look at these chains the same way I look at them,” said Muholi. “Do they represent something good, something beautiful or for entertainment, or will they trigger some flashbacks for those who are generations of those who survived or succumbed to slavery? All of those things have to do with being confined, or something that was used for work or other purposes. Once you see a lock, you see it differently.”

Muholi took a different photo almost every day for a year, and the photos included in the exhibition were selected from that larger body of work. Exhibition curator Renee Mussai, head of archive at Autograph, selected photos where “Muholi’s gaze is oppositional, scrutinizing, challenging and confrontational.” Autograph is a nonprofit UK organization that acquires historic and contemporary images, as well as commissions new photographic works, that explore issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice.

“Curatorially, I wanted to create a space where one cannot escape this gaze: a relentless dialogue of looking, and seeing, in the same way that their experiences of blackness and being, of traveling in the world in their black body, continuously in transition, facing racisms and phobias, is relentless,” said Mussai.

Indeed, Muholi’s gaze does seem to follow viewers around the gallery, compelling them to deal with whatever feelings the images evoke.

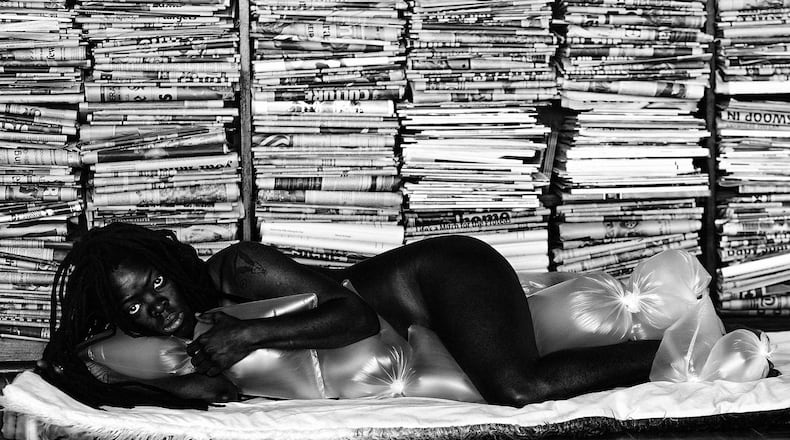

Muholi’s skin appears dark and luminescent in the images, qualities achieved in the editing process after the photos are taken, not with makeup or paint. They use toothpaste on their lips to create a stark contrast between the skin and mouth. In most of the images, the artist wears crowns and elaborate neck pieces they fashioned out of Brillo pads, safety pins, washing machine hoses and other domestic objects, turning items that have been used to keep black women small into symbols of honor. Looking at an image titled “Bester I, Mayotte,” which Muholi said reminds them of their mother, they explain how black women’s hair is often subject to scrutiny and how adorning that hair with unexpected objects turns bondage into freedom.

“Each and everything around my hair has its own politic,” said Muholi. “It can either be the [wooden clothespins] around my hair, which is a different kind of traditional crown, but it speaks of women and work. So there [in “Bester I, Mayotte”], my mom worked as a domestic worker for more than 42 years and that represents her in a way. I wanted to produce an image that represented her as a young, beautiful person.”

By using these objects out of their usual context and projecting black bodies proudly occupying space, Muholi hopes to inspire others to use visuals to tell their stories.

“My wish is to see many other knowledge producers taking this path to represent themselves, to project themselves,” said Muholi. “I know sometimes it’s unnerving and some people might think of it otherwise. But, we need to see many of us in different spaces. We shouldn’t wait for people to do us because it’s our time.”

EVENT PREVIEW

"Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness." Through Dec. 3. 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Tuesday-Friday, noon-4 p.m. Saturday. $3 suggested donation. Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, 440 Westview Drive SW, Atlanta. 404-270-5607, museum.spelman.edu. A poetry performance and panel discussion about issues facing black LGBTQI women hosted by poet Lyrispect will be held 2 p.m. Oct. 13.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured