Midway through the new “Framing Shadows” exhibit at Emory University’s Woodruff Library, there is an architectural rendering of a grand, neoclassical building.

Depicted is an elegant, two-story structure with arched windows and four Ionic columns that support a commanding portico. The sketch could be the schematic for a fine manor home or perhaps a vintage college library or study hall. But if a viewer leans in close, tiny letters inscribed on the pediment above the columns become legible: Black Mammy Memorial Institute.

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

The building was to have been constructed in 1911 in Athens. On its own, the sketch would be cause for pause. Yet surrounding it are a series of 19th century and early 20th century photographs that form the spine of the exhibit. They illustrate one of the main goals of the Georgians pushing for such an "institute": Creating a workforce of black women and girls whose job was to care for and clean up after white children.

The photographs compel and disturb: A black girl, perhaps no older than 13 years old, holds onto a white toddler just old enough to stand. Both are dressed in fine clothes, but the girl's face registers discomfort. In another, a very pregnant black woman holds a white baby in her arms. The infant rests on the side of woman's belly. Perhaps there was genuine affection between the caretakers and the children. But given the racial dynamics of the era, and the fact that some of the women in the pictures were enslaved, the viewer is left to wonder: What was life like for these black women and girls?

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

» PHOTOS | The 'Framing Shadows' exhibit at Emory

“Framing Shadows: Portraits of Nannies” is an unsettling exploration of power, gender and race, through the relationship of caretaker and child. The pictures were culled from the university’s Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection, a trove of thousands of photographs that document African-American life from 1840 to the 1970s. What makes the show even more compelling is that it is being presented at Emory during a time when colleges and universities such as Georgetown and Harvard are grappling with their ties to slavery and, in the case of Harvard, over who should have ownership of photos of enslaved people.

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

“Framing Shadows” does not engage those questions. It asks a related and equally frustrating question: If the women were important enough to photograph, why don’t we know who they are? Curator Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, who is a professor of African-American studies at Emory, said she’s hopeful her show will challenge viewers to consider the women and the reasons why their stories were rarely told.

“If we stay with the discomfort of looking at these photos, what you’ll get is a revealed humanity,” Wallace-Sanders said. “This isn’t a prop holding a baby. This is a real person, a real woman.”

“Rendering them invisible”

Wallace-Sanders has focused on a genre of photography as old as the medium itself: formal portraits of black nannies and their white charges.

Most of the photos she selected for “Framing Shadows” are from the 19th century, pre-Civil War. Others span from Reconstruction up to 1920. The composition in all is similar: A black woman is cradling or holding a white child she is responsible for looking after or helping to rear. It’s clear in each photograph that the main subject is meant to be the child. Scholars say it was the intent of the genre; the nanny was a status symbol.

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Barbara Krauthamer is the dean of the graduate school at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and co-author of “Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery,” a collection of photographs of what life was like for African Americans from Reconstruction to the 1930s. She has studied the nanny genre of photography for decades and said it was common not just in the South, but in the North and in Europe, especially among colonizers.

“It was a way for the white family to showcase their wealth and status, that they were wealthy enough to own a person who could be the caretaker of their child,” said Krauthamer. “Or later, if they had the wealth and status to hire someone to do that, because certainly the women appear in the photographs very nicely dressed and well composed.”

Krauthamer said the pictures were also meant to feign “benevolence” toward the women or to suggest they were treated “just like family.”

“But of course, they were not,” Krauthamer said. “It’s a way to make white supremacy benign in a visual sort of way.”

"This is a rescue mission for me. I am concerned that the lives of these African Americans will be lost and it's my mission to pay attention to them and honor their humanity." —Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, curator of 'Framing Shadows'

The images also represented what Rhea Combs calls the “schizophrenia of chattel slavery.”

White families “would love them as property and trust them to take care of their child, at the same time, dismiss them and discount them and not consider them fully human,” said Combs, curator of film and photography at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“It becomes a bit more complicated when you have black women who have been enslaved, serving in that role,” Combs said. “They are not supposed to be considered and looked at. That is a very, not only ironic way, but disturbing, troubling and confounding way of having someone fully present but rendering them invisible.”

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

“A rescue mission”

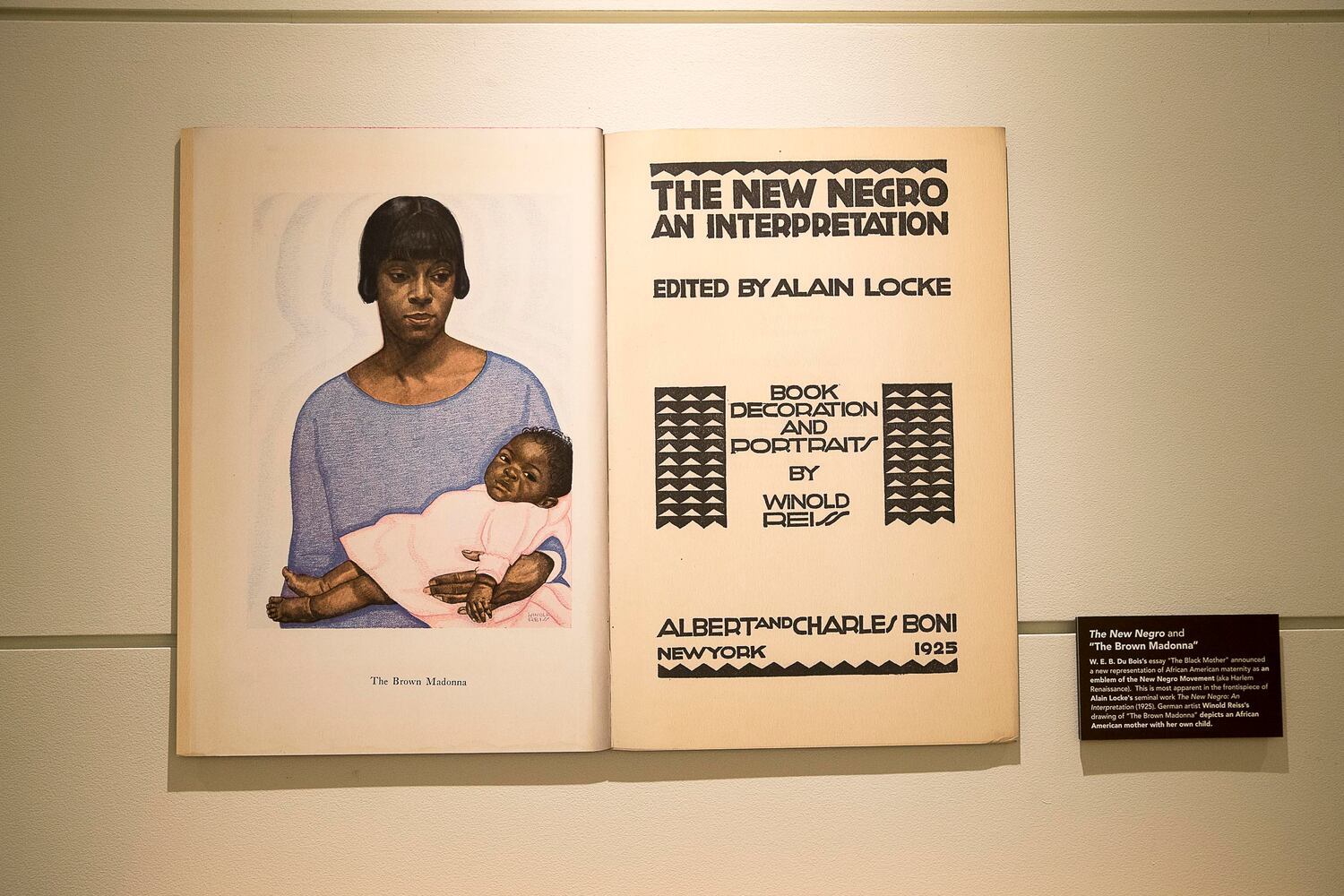

Changing that dynamic is Wallace-Sanders’ goal with this show. Extensive explanatory text accompanies most of the photographs. The exhibit is heavy on supporting material, such as drawings of the “institute” — which was never built — and essays by abolitionist Frederick Douglass, scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, playwright Alice Childress and poet Natasha Trethewey. All examine the stereotype of the black woman as “baby nurse,” wet nurse, child minder and “mammy,” which all have roots in slavery. Wallace-Sanders wants viewers to consider the women and girls apart from their roles as caretakers; as wives, daughters and mothers of their own children.

She began exploring the idea about seven years ago when Emory acquired the Langmuir collection. Within the scores of boxes was a folder labeled “nannies,” containing about 30 photos. Wallace-Sanders had already explored the caricature of black women made popular in the film adaptation of “Gone with the Wind” in her book “Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender and Southern Memory.” The Langmuir photos seemed another opportunity to continue the discussion about representation and the origins of stereotypes, but through the power of photography.

“This is a rescue mission for me,” Wallace-Sanders said recently, standing in the Emory gallery. “I am concerned that the lives of these African Americans will be lost and it’s my mission to pay attention to them and honor their humanity.”

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Only a few of the photos had accompanying letters or postcards revealing the names of those in the images. When the children are named, rarely are the women. When they are, they are identified by their role to the child: “Elizabeth C’s Mammy.”

Scholars have relied on the letters, memoirs and oral histories of the children once they became adults to glean any details about the lives of the hundreds of black women who posed for those pictures. It was atypical for a domestic worker to pen her own narrative about her experiences. Rarer still for an emancipated woman to have done so.

“There were so many stereotypes and caricatures about these women, and one is that they preferred the white children they took care of to their own,” Wallace-Sanders said. “Because she, ‘Mammy,’ was a tool of a pro-slavery agenda. The idea was she was not interested in freedom, not interested in equality and that she knows, sees and accepts herself as inferior.”

How viewers respond to the photos may depend on their personal history and relationship to domestic workers as much as their race. Krauthamer said when she has given talks about similar photos, inevitably a white audience member has come up afterward and talked in pained and glowing terms about the African-American domestic worker who cared for his or her family, or perhaps a grandparent or great grandparent. Sometimes the person brings along the photo.

“It was always a tremendously uncomfortable moment because the person was clearly invested in and attached to the ownership of this picture and wanted to share it as a point of pride and connection,” Krauthamer said. “And yet, the story that they’re telling is one of slavery or Jim Crow.”

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

And for an African-American viewer, given that domestic work was one of the leading means of employment for black women well into the 20th century, the photos could also conjure conflicting emotions. They may see women who remind them of women in their own families who made tremendous sacrifices while employed as domestics. Wallace-Sanders said she wants all viewers to put their own stories aside for a while and focus on the women in front of them.

“Stay with her, think about her a little while longer,” Wallace-Sanders said. “If you’re here to see these photos, you have to be willing to learn something about this country’s history.”

"Framing Shadows: Portraits of Nannies from the Robert Langmuir African American Photography Collection," on view until December 31.

Emory University, Robert W. Woodruff Library’s Schatten Gallery, level 3, 540 Asbury Circle, Atlanta.

For more information and library hours:

“Framing Shadows/Framing Lives: A Rosemary Magee Creativity Conversation” with Spelman President Mary Schmidt Campbell and Emory University Associate Professor of African-American Studies Kimberly Wallace Sanders.

Wallace-Sanders is the curator of the photography exhibit, “Framing Shadows: Portraits of Nannies from the Robert Langmuir African American Photography Collection.” Campbell and Wallace-Sanders will discuss the new exhibit that examines image of African-American women as child care providers for white children from 1840 to the early 20th century.

Wednesday, 6 p.m to 8:30 p.m.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured