THE NEW CLASS: First-time teachers apply lessons learned to next steps

Daniel Garcia’s last days of the school year didn’t go as expected — not much had throughout his first year of teaching.

The social studies teacher at Gwinnett County’s Shiloh Middle School had finished delivering his lessons and grading his tests on a recent afternoon. He reflected on his struggles to manage the classroom and the adjustments he made to form meaningful connections with students.

He had planned to show them a movie relevant to the curriculum, but had a change of heart. “They’re not gonna watch ‘Gandhi,’ ” he said.

He opted to put on “Puss in Boots” — students implored him earlier in the year to see the sequel in theaters. Garcia posed for photos with students and let them teach him his first TikTok dance. They shared kind messages and let Garcia know that they enjoyed his class.

“It’s really nice. I feel like it was a job well done,” he said.

Garcia’s first semester was difficult, marked by several student fights and behavior he couldn’t control. Even as he became a better classroom manager and students’ behavior became less severe, he felt unsupported and overburdened.

“Whenever something goes wrong, the blame and the onus is always on the teacher,” he said.

Around the midway point of the school year, Garcia initially considered requesting a transfer but learned Gwinnett typically doesn’t allow teachers to change schools until they’ve worked in their original school for three years. That helped seal his decision not to return to Gwinnett.

He is preparing to move back to his native Idaho, where he’ll teach middle school social studies in English and Spanish. He’s optimistic the new job will be a better fit.

Morale quandary

School districts in metro Atlanta hired thousands of first-time teachers for the 2022-2023 school year. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution followed three of them throughout the year, including Garcia. Two of the three are leaving their jobs, citing challenges in the classroom and outside of it. Such turnover is a concern for education leaders in Georgia and nationwide.

Retention rates for first-time teachers vary across metro Atlanta school districts. DeKalb County reported 3% of new teachers are leaving the district at the end of the year. In Clayton and Fulton counties about 10% are leaving. Cobb County expects anywhere from 5% to 15% of its first-year teachers to leave.

In metro Atlanta, teacher retention rates usually trend lower than the state average. Many of them will stay in teaching, but change jobs or move to new districts. It’s a more and more common occurrence, said Russell Olwell, the associate dean of the Winston School of Education and Social Policy at Merrimack College who helped conduct a national survey in May about teacher morale.

“Teachers are looking at their individual situations. Previous generations of teachers might say, ‘I’m going to stick it out,’ ” he said. “Now people have lost patience. They’re more willing to leave.”

The survey found that teacher morale in 2023 increased over the previous year, but is still troublingly low. More than half of teachers said they would advise their younger selves against the profession.

The pressures of the job were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, said Deborah Margolis, dean of the Winston School. But that’s starting to change.

“I think we’re seeing things turn in the right direction,” she said. “I think that the findings of the survey are really that the younger teachers are feeling better about everything than some of the more seasoned teachers.”

How districts are dealing with it varies widely across the country. Many are offering bonuses (with various strings attached) using federal pandemic aid. Others are offering training opportunities and more mental health support. Locally, the Cobb County School District is paying for some teachers’ advanced degrees, and incoming DeKalb Superintendent Devon Horton has emphasized the effectiveness of grow-your-own teacher training programs.

Gwinnett is focusing on retention by revamping its onboarding process and creating leadership paths for teachers to be more involved in mentorship and instructional practices. A talent management consultant drew attention months ago when it highlighted that 40% of new teachers hired in the 2018-2019 school year left the district by the end of their third year. The national average is about 30%.

The last day of school, the overwhelming feeling was relief, said Garcia, who is leaving Gwinnett. But it was bittersweet for both him and his students.

“Just seeing the differences from the beginning all the way to the end — they’ve grown so much. And I’ve learned a lot from the kids,” he said. “This experience has helped me grow a lot.”

Throughout the year, he spoke of projects that got students excited and lessons that connected to their sense of identity. He had camaraderie with colleagues and learned how a pair of flashy shoes — he sported black and red KDs for the last day of school — could make inroads in the classroom.

But moments of fatigue and frustration ultimately outweighed the sense of fulfillment.

Garcia said among the most important lessons he learned in his job were guideposts for deciding his next job. He drew on personal experience in an interview when a principal gave him the chance to ask questions about his school.

“Do you have enough substitute teachers?” Garcia asked his prospective boss.

“Will administrators fill in for teachers when necessary?”

“Are teachers compensated if they lose their prep period because of other responsibilities?”

The answers to those questions, he said, were all yes.

On to the next

On a trip to the state Capitol near the end of the school year, third grade German immersion teacher Brandon Wyatt was stressed. His students were thrilled to be out of school for the day, elated for the impending summer vacation — safely crossing busy streets in downtown Atlanta and staying together as a group were not their top priorities that day, to Wyatt’s dismay.

“I was sitting there going through my papers, making sure I got everything.” he said. “And one of my students reached up as high as he can — he’s short, so about my mid-back — and goes, ‘It’s going to be OK, Herr Wyatt. It’s going to be OK.’ Like, this 8-year-old is comforting me.”

It’s a mark of how much his students have grown over the year, Wyatt said, that one of them noticed his stress and tried to comfort him. And a sign of how difficult the year was for him.

“My brain is scrambled eggs,” he said.

His main feeling after the last day of school was relief. He went home, put on a tropical printed shirt and exhaled for what felt like the first time in months.

Next year, Wyatt won’t be returning to teach at DeKalb’s Ashford Park Elementary. He accepted a position teaching German at the University of North Georgia. It’s the job he was interested in all along, having earned a master’s degree after studying German in college.

“Hopefully my niche is college students,” he said.

He hopes that there will be less of the feeling of being under a microscope. As the teaching profession becomes increasingly politicized, the pressure of getting in trouble for saying the wrong thing was almost as distracting to Wyatt as the pressure to get his students through the academic material.

Like Garcia, Wyatt is still drawn to teaching after a year in a setting that wasn’t a good fit for him. He learned that teaching elementary students, as rewarding as it could be, was not for him. He learned that you can never tell what a third grader is going to say next. And he learned what it means to persevere.

“The person that I feel like I am today and the person that I felt like I was a year ago? Totally different,” he said. “Oftentimes, when I was younger, it was so much easier to say, ‘If I don’t start, I can’t fail.’ But you know, I considered giving up a couple of times throughout the year, but I’ve stuck it out. I’m really proud of myself.”

A new beginning

For Ku Htaw, a math teacher at DeKalb School of the Arts, the end of the year doesn’t feel like an ending. It feels like a beginning.

She’ll be back at the same school next year, teaching the same subject. And she wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I expected to have struggles through the first year, but I think I’ve managed pretty well,” she said. “Before I became a teacher, I heard a lot of things: Teaching is really hard, you have to deal with students, administrators and everything else. And I can see that — but I think that what I’ve learned is you don’t have to make teaching complicated.”

According to the numbers, Htaw is in the majority: Year over year, most teachers stay in their jobs. But the profession is still in the midst of a reckoning, and school districts are still learning how to help teachers.

“The general public is learning that teaching is a stressful job,” said Margolis, dean of the college that conducted the teacher morale survey. “We need to take care of our teachers, we need to help them take care of themselves, because that’s in turn the best way for them to take care of the next generation.”

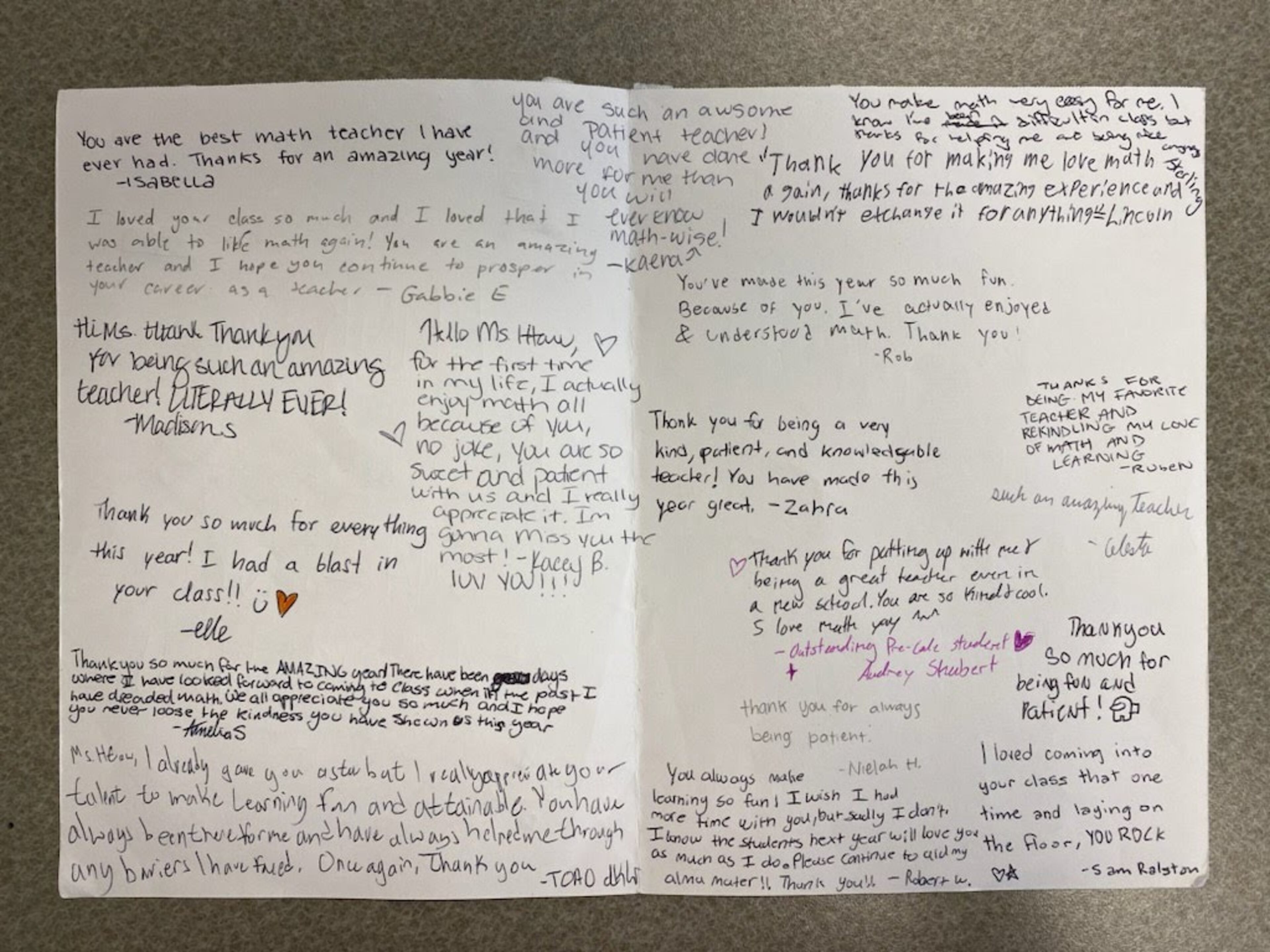

The year has certainly been a learning experience for Htaw. Each day, even each class period, was an opportunity to get better. She prioritized connecting with students and being patient with them. And they’re grateful she did.

“For the first time in my life, I actually enjoy math all because of you,” one student wrote in a card to Htaw. “Thank you for making me love math again,” wrote another.

Through those relationships, she saw her students improve academically. Two students in particular who weren’t doing well throughout the year improved enough to pull their grades up to A’s after taking the final exams, she said.

“I think that’s one of the defining moments,” she said. “You know it’s in them — you just have to push them to reach that point.”

At the same time, Htaw is pushing herself. She wants to find ways to integrate new types of lessons into her classes next year. Always the learner, she’ll be attending several training sessions over the summer. And she’s hoping to start a master’s program in the fall, with plans to study how education and technology intersect.

As she cleaned out her room on the last day for teachers, she carefully tucked what looked like foam boards behind the desk. Ceiling tiles. She’s been teaching in a room where a few dozen of the ceiling tiles were painted by past students, each bearing a math reference or an inside joke they shared with other teachers. This year, some of Htaw’s students gifted her new tiles painted with their own jokes. She plans to add them to the colorful display to make the room a little more her own.

For now, the tiles sit behind the desk, waiting for her to return from the summer break and get started on the rest of her what she hopes will be a 30-year career.

“One year down, 29 more to go,” she said.

About ‘The New Class’

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution followed three new teachers in their first year in the classroom. As metro Atlanta school districts continue struggling to fill open teaching positions, these teachers provide an in-depth look at what it takes to do the job. In this multipart series, we explored how they navigated learning challenges and tried to stave off burnout — all while trying to keep sight of why they got into teaching. You can read the first installment here and the second installment here.