Over 38 years, Emory students quizzed and grew to love Jimmy Carter

For generations of Emory University students, Jimmy Carter was more than just the nation’s 39th president.

He was their beloved professor.

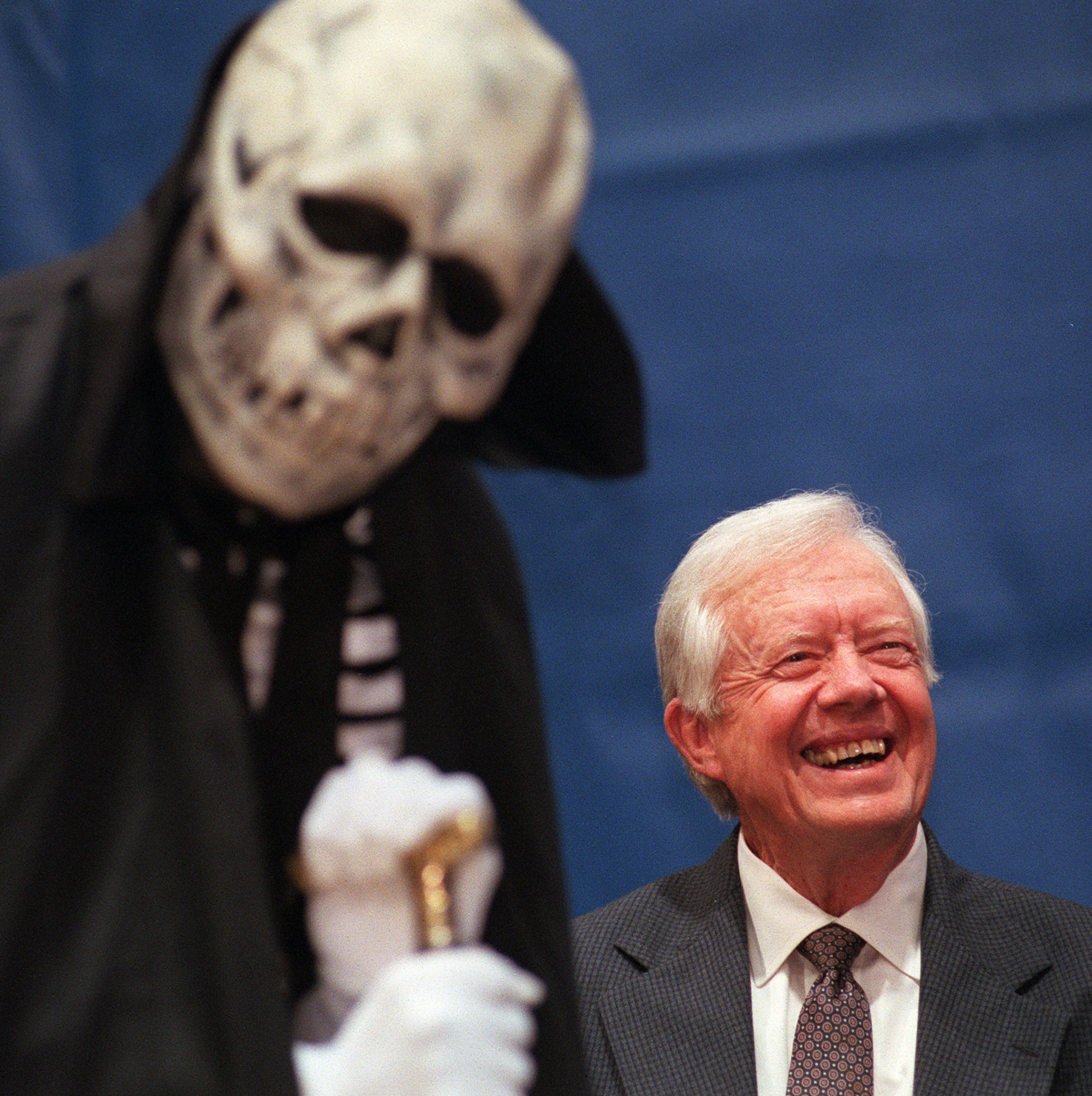

Carter drew packed crowds to his annual town halls where he inspired students with his candor, quips and wisdom.

For 38 consecutive years, starting in 1982, Carter was the keynote speaker at an event that became a cherished tradition for first-year students. He made his last appearance in 2020. Emory estimates about 50,000 students attended the Carter Town Hall over the decades. Held early in the first semester, the freewheeling discussions left a lasting impression.

“This was someone who my whole life had been larger than life for me,” said Jessica Corbitt-Dominguez, a 1995 Emory graduate, who is now the spokeswoman for Fulton County government.

She grew up in a working-class family with deep Georgia roots who were immensely proud that Carter hailed from their home state.

“That town hall really made this huge impression on me,” she said. “The conversation became so much bigger and about solving these huge world problems.”

After graduating from high school, Carter studied at Georgia Southwestern College, now called Georgia Southwestern State University, and transferred a year later to Georgia Tech to study mathematics for a year in order to qualify for the U.S. Naval Academy.

But some of Carter’s strongest educational ties were with Emory, Georgia’s largest private university. Alumni fondly recall their interactions with Carter, 98, who entered home hospice care last month.

His connection grew out of conversations he had with the school after losing the 1980 election. He partnered with the university to create the Carter Center, received the title of distinguished professor and regularly lectured in religion, politics or other courses.

He met monthly for lunch with a small, rotating group of faculty members and had frequent breakfasts with Emory’s then-President James T. Laney and his successors.

”There was, I think, first of all a sense of pride that this was the only university in the country that had a former president of the United States actually on the faculty, and not in a symbolic way,” said Gary Hauk, a retired Emory administrator and university historian. “He valued the academic life, but he valued it most when academics got translated into action that benefited the world.”

Carter told students they could ask him anything.

In 1998, he had avoided addressing the Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky scandal — until that year’s town hall. He told the audience he did not believe Clinton had been truthful to a grand jury.

“He basically found it ethically problematic ...,” recalled Julie Clements Smith, a 2002 Emory graduate.

Carter abided by his pledge to answer all questions, even the uncomfortable ones. His remarks sparked national headlines.

“He sort of lived out in these town hall meetings what he swore to do as president, which was to tell the truth,” Hauk said.

And that’s how it went for decades: Moments of levity mixed with poignant reflections and political insights.

During a town hall a few days after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Carter offered comfort: “Our nation will survive, as it always has.”

A month after his 2015 cancer diagnosis, he told students that he turns to prayer amid adversity. The next year, he was back on stage decrying the state of American politics but reminding students of the nation’s resiliency.

Some of the conversations were out of this world.

Dr. Dean Dalili of Houston, Texas, attended eight town halls between 1994 and 2002 while he was an undergraduate and medical school student at Emory. Dalili said he once asked Carter whether, as president, he had seen proof of alien life.

“His answer was ‘no,’” Dalili recalled. “But as governor of Georgia he was out riding horses with two neighboring governors and saw a flying object that came over a pine tree, hovered silently and changed colors before flying away and he thought that might have been a UFO.”

Occasionally, silliness ensued.

One student recounted how Carter once joined in the laughter when a classmate submitted a question under the fake name “Ben Dover.”

In 1989, Carter arranged for peace talks between the Ethiopian government and Eritrean rebels to take place in Atlanta. Still, he found time during the negotiations to attend the town hall.

He discussed Cuba and refugees who were fleeing the country by rafts at another event. Carter, who was president during the Mariel Boatlift in 1980, told students: “Fidel Castro has my phone number, and he has called me in recent weeks.”

On the dispute over Georgia’s state flag that featured a Confederate battle emblem, Carter said in 1996 that the flag wasn’t racist, though he had supported efforts to change it.

In 2018, he told students that global warming was the greatest threat facing their generation. And then, the world’s best-known peanut farmer dropped a peanut butter-covered bombshell: He preferred creamy for sandwiches, and crunchy on a cracker.

Jonathan Kopp, a 1988 graduate from New York, knew little about Georgia before deciding to go to school here.

“President Carter put Emory on the map for me,” said Kopp.

Kopp recalled how willingly Carter stopped for autographs and how he once stood in the salad bar line at the dining hall with a plastic tray, “just like anyone else.”

Elisabeth Nelson, a 1999 graduate from Seattle, said Carter — a former U.S. Navy lieutenant — once approached her on campus to ask about her U.S. Navy shirt.

“Nice T-shirt. Go Navy,” he said.

“I think I stammered out a ‘thank you, sir,’ completely caught off guard and blown away by his kindness and casual comment,” she said, in an email.

As Carter’s public life slowed down, Emory brought in Olympic soccer gold medalist Megan Rapinoe and former United Nations Ambassador Andrew Young to speak at the town halls.

At a virtual town hall in 2020, Carter’s grandson Jason took over. That year, in a recorded video message, Carter offered advice on how to respond to curious students: “Don’t avoid the questions and answer it forthrightly.”