Metro Atlanta schools embrace a fourth R: Resolving conflict

The Jean Childs Young Middle School student was angry.

An older boy started picking on her on the bus, who then followed her into the cafeteria during breakfast. He wouldn’t stop taunting her. By the time class was about to start, she ran at him, and had to be pulled away by a group of adults.

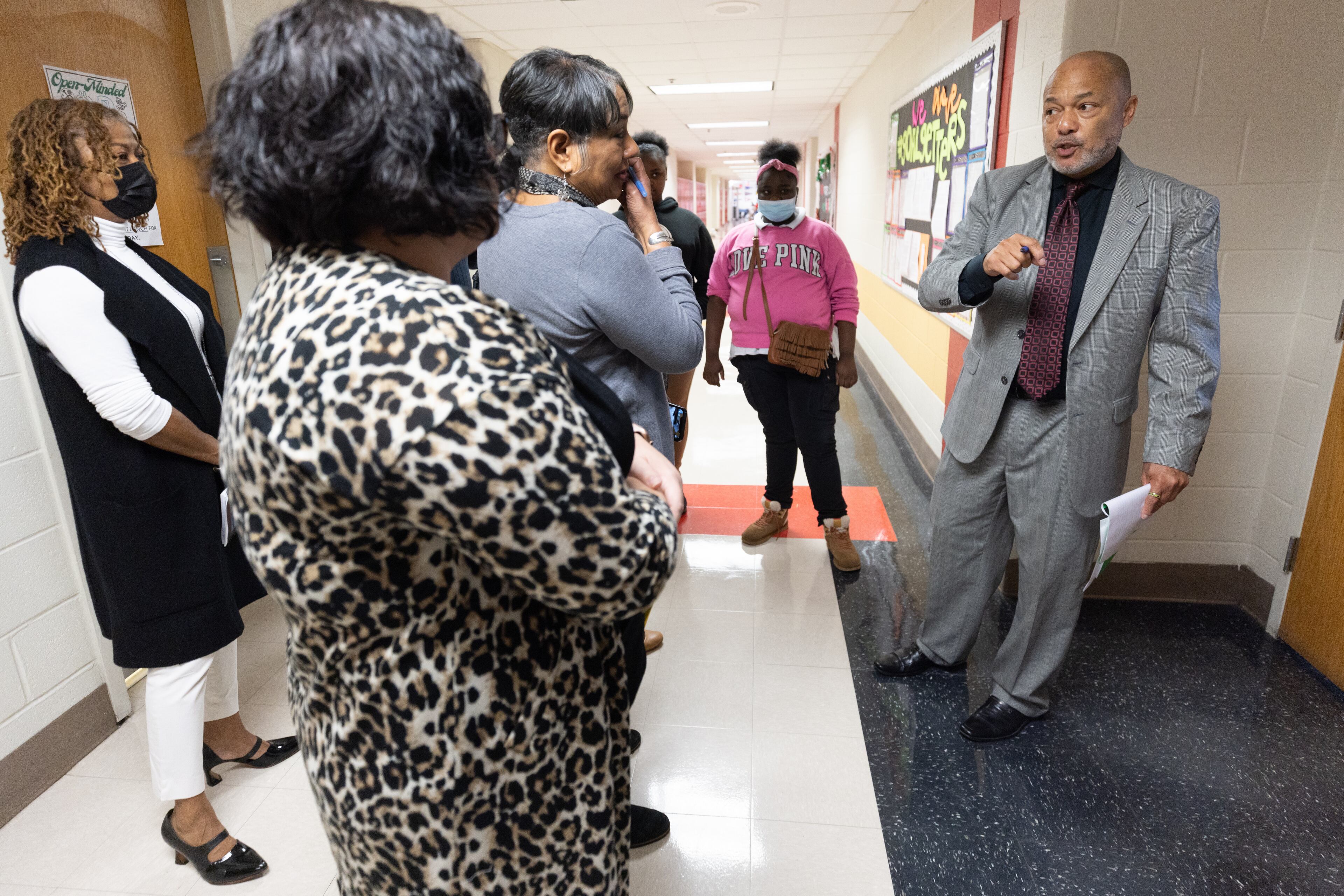

She didn’t realize she’d be running straight through a group of educators from around the country, touring the campus that morning to learn how the school teaches students conflict resolution skills and emotional literacy. The visitors didn’t realize they’d get a real-life example.

In another time, at another school, both students may have been sent to the principal’s office to be punished. Instead, a district official there for the tour pulled the girl aside, and they discussed better ways she could have dealt with the conflict. She gave the student something else, too: the promise that she would be back to check on her.

By the time the student made it to class 15 minutes later, she was calm.

“Students are going to have issues and concerns,” Principal Ron Garlington said later to the visitors. “But the key is, how do you respond to it?”

It’s the question reverberating throughout Atlanta.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has counted at least 11 minors who were arrested in the death or injury of another child with a gun in metro Atlanta so far this year. When a 12-year-old and a 15-year-old died in a November shooting near Atlantic Station and three teenagers were arrested for the crime, local leaders called for changes: more parental involvement, more cameras or curfews, or help from the community. Atlanta’s mayor, its top school district leaders and its student advisory council held a rally Thursday evening to take a stand against youth violence.

Atlanta, like many major American cities, has experienced an uptick in gun violence since the pandemic. A large share of the victims and suspects are juveniles and young adults. Additionally, metro Atlanta school districts have reported a surge in fights and other incidents of violence since in-person learning resumed.

Officials in Atlanta Public Schools and the DeKalb County School District are investing in programs like the ones at Jean Childs Young Middle School. They’re putting time into teaching students, like the one in the hallway, how to peacefully de-escalate and resolve conflicts.

“This place was a nightmare when I got here in 2014,” Garlington said. Then they built the Wolf Den, a one-stop shop to meet students’ behavioral and mental health needs, as well as basic needs like food and clean clothes. They started an expansive mentoring program, and lessons about social and emotional skills.

The Georgia Department of Education has considered Jean Childs Young Middle one of the state’s lowest-performing schools since before the pandemic started. But thanks to the school’s academic progress — fueled by improved attendance and fewer instances of violence — it was taken off that list this week.

“It feels good coming to school now,” Garlington said. “Even on the worst days.”

Turning around a difficult year

The academic year at Towers High School in DeKalb County started with a series of fights that disrupted the school day. One in September involving at least a dozen students resulted in at least three arrests and several minor injuries to staff members.

“I knew then that we had to come up with something else,” said Principal Tiffany Sims. “What we discovered is that our students, the problem that they come to school with at Towers High is that they do not know how to resolve conflict.”

The school reached out to churches, business owners and parents. It launched an improved program for mentors to drop by and check on their students. It hired a parent liaison and a licensed counselor to train the staff on anger management techniques. It created a calming room for students and one for staff, so they can take breathers when they need to.

“It’s different” in school now compared to the beginning of the year, said Towers High senior Jayden Chick. “I feel like the fighting has stopped and things have calmed down.”

Jayden, a group commander in the school’s JROTC program, said she’s noticed a change in her friends. One of them told Jayden that she wanted to fight someone, but calmed down when she thought about her mentor.

“We just have to make sure that we’re being consistent and that we can sustain that work that we’re doing,” Sims said.

Post-pandemic challenges

Consistency has been hard to come by in recent years thanks to the pandemic. Some students are struggling with traumatic events they’ve endured — like losing loved ones or changes in economic circumstances. Towers High’s homecoming queen Jaynee Chavez, 17, was killed in November when someone opened fired on her car.

Big Brothers, Big Sisters of Metro Atlanta, which partners with schools around the metro area to provide mentoring to students, saw demand for mentors skyrocket since the pandemic. CEO Kwame Johnson said 99% of the students in their programs never touch the criminal justice system.

That’s the goal with programs like the ones being implemented around the city.

Students at Jean Childs Young Middle School start some days by walking up to the board and circling what emotion they’re feeling. Some say they’re “chill,” or “bored,” or “drained.” On a recent Monday, very few students said they felt happy. They broke into groups and talked about why they felt a certain way.

The exercise only lasted about five minutes — but it was a powerful reminder to the students that it can be good to stop and think about what’s causing their emotions. That adults at the school care how they feel. That their classmates are dealing with the same issues. That they’re not alone.

“I think it’s our responsibility as a city for everyone to step up,” Johnson said. “We can’t just watch the news and complain — we all gotta step up.”

Our reporting

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has looked at the challenges concerning youth violence in the region. The AJC is documenting efforts by local government, school districts and law enforcement to find solutions.

How to volunteer

- Contact the district: Visit the websites for Atlanta Public Schools or the DeKalb County School District.

- Contact a school: Reach out to the school in your neighborhood for more information.

- Contact Big Brothers, Big Sisters of Metro Atlanta: Visit the organization’s website.

Reaching vulnerable students

The DeKalb County School District next week will roll out a program that’s been in the works for a long time, said Executive Director of Public Safety Bradley Gober.

The Legacy Academy kicks off with a three-day Winter Bliss program for about 25 boys in seventh, eighth and ninth grades. They’ll play games and conduct science experiments — but most importantly, they’ll talk to the adults. Hopefully, Gober said, it will build trust between students and adults.

Programs like this often target boys who are 12-15 years old, because of how many changes they go through at that age. They’re vulnerable to making missteps.

“We knew that we were not going to be able to arrest our way out of the issues that we saw coming,” Gober said. “We want to kind of guide them in a way to give them the tools to make better choices. And if they do make bad choices, make those bad choices they’ll be able to come back from.”

That’s the goal of these programs, the school officials say.

“These are life skills that they can use outside in the community to help curb some of this violence and hopefully keep them safe, their friends safe, their family safe,” Gober said. “They can go on to be productive adults and lead productive happy lives.”