In DeKalb, one-on-one mentoring showing early success for at-risk students

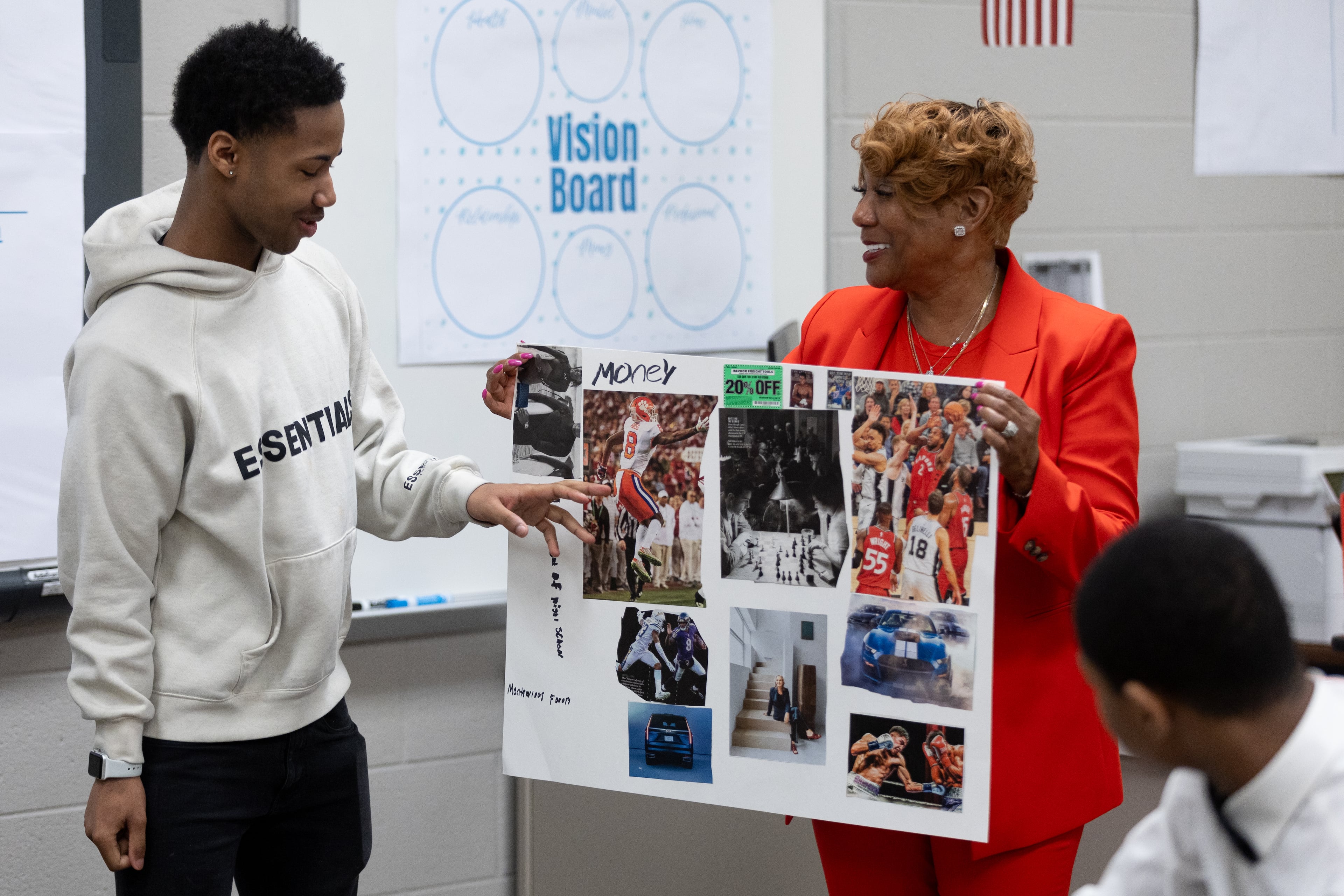

A group of Redan High students leafed through piles of magazines, trying to see their futures in the glossy pages.

The roughly 15 students — all of whom faced challenges like poor attendance, frequent discipline issues or low grades — were making vision boards on one of the last days of the academic year. They cut images and words out of the magazines and reassembled them on posters, to serve as reminders of what they’re working toward.

Leading the exercise were Melinda Adams and Gail Jones, the students’ mentors, confidants and advocates. They’re two of about four dozen new employees in the DeKalb County School District called FACE advocates. FACE is an acronym, standing for “family and community engagement.” They act as one-on-one mentors to some of the district’s most at-risk students, helping them navigate the sometimes rocky path toward graduation.

“We don’t give up on them,” Adams explained. It’s what draws the students to them and makes the partnerships so successful, several students say.

DeKalb spent more than $1 million to hire 45 advocates this school year who are at work in roughly 20 schools where students are more likely to become dysregulated.

The district preselected students for the program based on data like attendance and grades. Schools could add students based on their needs and choose who would most likely benefit.

Some of the students were recently back from stints at an alternative school after various disciplinary infractions. Others were failing almost all of their classes a few months ago.

“The teachers wouldn’t look out for me how they used to,” said 17-year-old Anton McLean, a rising senior, as he flipped through a magazine. He couldn’t even blame his teachers, he said, because he wasn’t doing what he was supposed to. “So when (Jones) came, it was just perfect timing.”

Standing behind him, Jones stepped in: “Remember, sometimes it’s not that the teachers don’t care for you,” she said. “It’s just that they have so many students they have to deal with.”

That’s what separates the FACE advocates from a lot of other adults at the school: Their focus is entirely on the 10-12 students they work with. They don’t teach classes. They work with the students to develop good study habits, make it to class on time, learn to avoid peer pressure and conflict. They also work with their families, keeping them in on the conversation and helping to connect them to resources when necessary.

And as the Redan High students have gotten to know Adams and Jones, they started to feel like they had someone to answer to. They describe standing in the hallway with their friends, then suddenly finding themselves being escorted to class. They roll their eyes as they tell the story, but they’re smiling too.

“I can talk to her any time,” said 18-year-old Keondre Walker about Adams. He’s been sent to an alternative school twice for discipline issues and said before meeting Adams, he didn’t really take school seriously. But he graduated on May 15 with plans to enroll in the U.S. Army.

“She really cares for me,” he said.

Superintendent Devon Horton has been discussing plans to hire advocates like this since he was hired last year to lead the state’s third-largest school system, which is no stranger to mentoring programs. Individual schools like Towers High have relied on members of the community to act as mentors for students, and the public safety department has hosted activities for male students during breaks to create bonds with the school district’s police department.

But the shooting deaths of two DeKalb students within two days of each other in the fall semester was evidence of how necessary the FACE advocates are, Horton said at the time. Some students needed more direct mentoring, he believes.

It’s too early to have much data about the success of the FACE advocates (Jones, for example, started working at Redan High in February). But Principal Vitella Dodson has noticed a decrease in discipline infractions and an increase in attendance. Students who worked with an advocate said their grades are up.

Their vision boards boasted photos of expensive cars and big houses, but also the logos of several historically Black colleges and universities and fraternities and sororities they wanted to pledge, or images to denote their plans to become politicians, chefs or personal trainers.

“I’ve just been cruising through life, cruising through school without a thought in mind about what I would really be doing in life,” said Khameel Williams, another senior who graduated May 15. With the help of an advocate, she figured out a plan to go to a community college on her way to becoming a veterinarian. “I plan on being very successful. That’s really my main focus.”