Gwinnett newcomer center bridges path to education for immigrants

Blanca Torres Jimenez’s first couple of weeks in the U.S. were fairly easy — “normal,” she described it during a recent visit to the Gwinnett County Public Schools’ International Newcomer Center in Lawrenceville, where she and her siblings were preparing to enroll in new schools.

Mom’s cooking is still best, but Torres Jimenez liked the Chinese buffet. The burger she tried not as much. She has enjoyed the weather and said the area feels much bigger than the part of Michoacán, Mexico, from which she moved.

Soon she’ll start classes to finish her senior year of high school, and a team in Gwinnett County Public Schools will strive to make transitioning into school as easy as possible for her and her family.

For more than 30 years, tens of thousands of immigrants who come to Gwinnett, the largest and most diverse school district in Georgia, have visited the International Newcomer Center. The staff assists students in grades six through 12 with enrolling in classes and filing transcripts. They assess students’ math and English skills, along with their literacy in their home language. Parents participate in an orientation to become familiar with the district and can also take classes if they want help with English. In some respects, the center is their Ellis Island.

The district is about as global as a school system can be, with students speaking about 100 languages and coming from almost twice as many countries.

That means demand at the newcomer center is high and likely to increase as Gwinnett grows and demographics change. Last school year was the center’s busiest, according to available records, with 2,736 students visiting. This school year, that number is already past 1,600. A team of four full-time student advisers, along with part-time staff and seasonal help for the busiest times of the year, can see up to 50 new families in a day, inevitably encountering languages that no one on staff can speak.

Gwinnett celebrates its diversity as a strength, but it brings challenges. Multilingual students are performing below district and state averages on standardized exams. A small percentage of its teachers are considered bilingual.

While the center isn’t in the classroom, its staff are often the first district representatives to greet the newcomers and play an important role in setting them up for success. The staff strives to make the families and students feel welcomed and — as much as possible — not overwhelmed.

“We have a conversation to learn about the family,” said Lynnette Aponte, director of the newcomer center. “The families have questions about how the school system works, and we bridge the gap” to their new schools.

Torres Jimenez said she felt ready for school, where her favorite subject is language arts. Her youngest sister had nerves about kindergarten. Martha Alicia Jimenez Zarco, the girls’ mother, said through an interpreter that her youngest eventually came around because she’s eager to meet and to play with the other kids.

A growing need

The center started at Meadowcreek High School about 30 years ago with help for Spanish speakers. Most of the families who visit the center continue to come from Latin America. A quarter of Gwinnett students are multilingual, and 78% of those students speak Spanish. One-third of students are Hispanic, the largest demographic in the district. Aponte said the nationalities they have seen most this year are Guatemalan, Honduran, Mexican, Venezuelan and Vietnamese.

Due to evolving needs in the community, the center added Vietnamese and Korean. Years ago, Aponte said, a need to serve Balkan families emerged, and the center hired a student adviser who speaks Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian. Just last year, an adviser who speaks Chinese joined the staff.

Other metro Atlanta districts have similar centers for international students, but Gwinnett’s is the largest, with a variety of languages and services that reflects the level of demand in the county.

Along with their work with students and their families, center staff also translate documents and provide interpretation during events and parent teacher conferences. Inevitably, families come to the center without sharing a language with any staff. In those instances, they rely on technology to translate.

Aponte said families come to the center in a variety of ways. New families often follow friends or relatives to Gwinnett or find people with common backgrounds through church or community groups. Those networks often direct families to the center. If they visit their schools first, staff will also refer them to make an appointment with Aponte’s team.

The center does not provide any different services or resources for students or families that may be undocumented. In fact, it does not even ask because the district doesn’t need that information, Aponte said: “We serve all students regardless of their status.” National figures are inexact, but it’s estimated about 23% of immigrants are undocumented.

The gaps in performance, bilingual educators

Some in the district, including school board members, have drawn attention to the importance of better serving multilingual learners and also highlighted achievement gaps for Hispanic students.

Teachers told leaders in March that standardized tests delivered in English to multilingual students produce results that reflect their knowledge of English, not what they’ve learned. They said those results can be discouraging. Just under half of all Gwinnett students in grades 3 through 8 scored proficient in English language arts on the most recent Georgia Milestones. Multilingual and Hispanic students each scored about 30% proficient.

The district has focused on hiring more diverse teachers, recently launching recruiting efforts in Puerto Rico and offering incentives for multilingual teachers. Only 371 of about 12,000 current teachers are considered bilingual. About 10% of new teachers this school year are Hispanic, outpacing the overall teacher workforce, which is about 7.4% Hispanic.

Aponte said she knows from her personal experience it’s valuable when a student sees teachers and school leaders who look like them and also can relate to their experiences. She moved to Gwinnett from Puerto Rico as a young adult and spent her initial time here improving her English. She recalled a film class at Georgia State University and not understanding much of the discussion or the movies they watched.

That experience helped her relate to many students as a teacher and assistant principal at Meadowcreek and now at the International Newcomer Center.

“You just never know the impact that you have on students,” she said, sharing a story of running into former Meadowcreek students who are now teachers in the district. “When they see someone who looks like them in a certain position, they think, ‘I can do that, too.’”

She takes pride in making the center a welcoming and reassuring place. Staff have posters in their offices in different languages and have contact info for WhatsApp, a popular communication app among many immigrant families, particularly useful for reaching relatives overseas.

Breaking barriers

While Aponte manages with the staff available and temporary employees when demand is highest, she said she would gladly hire an additional adviser. If she could add a language to the center’s roster, it would be French to accommodate a growing population of African immigrants in the county, including Yannick Mandeng.

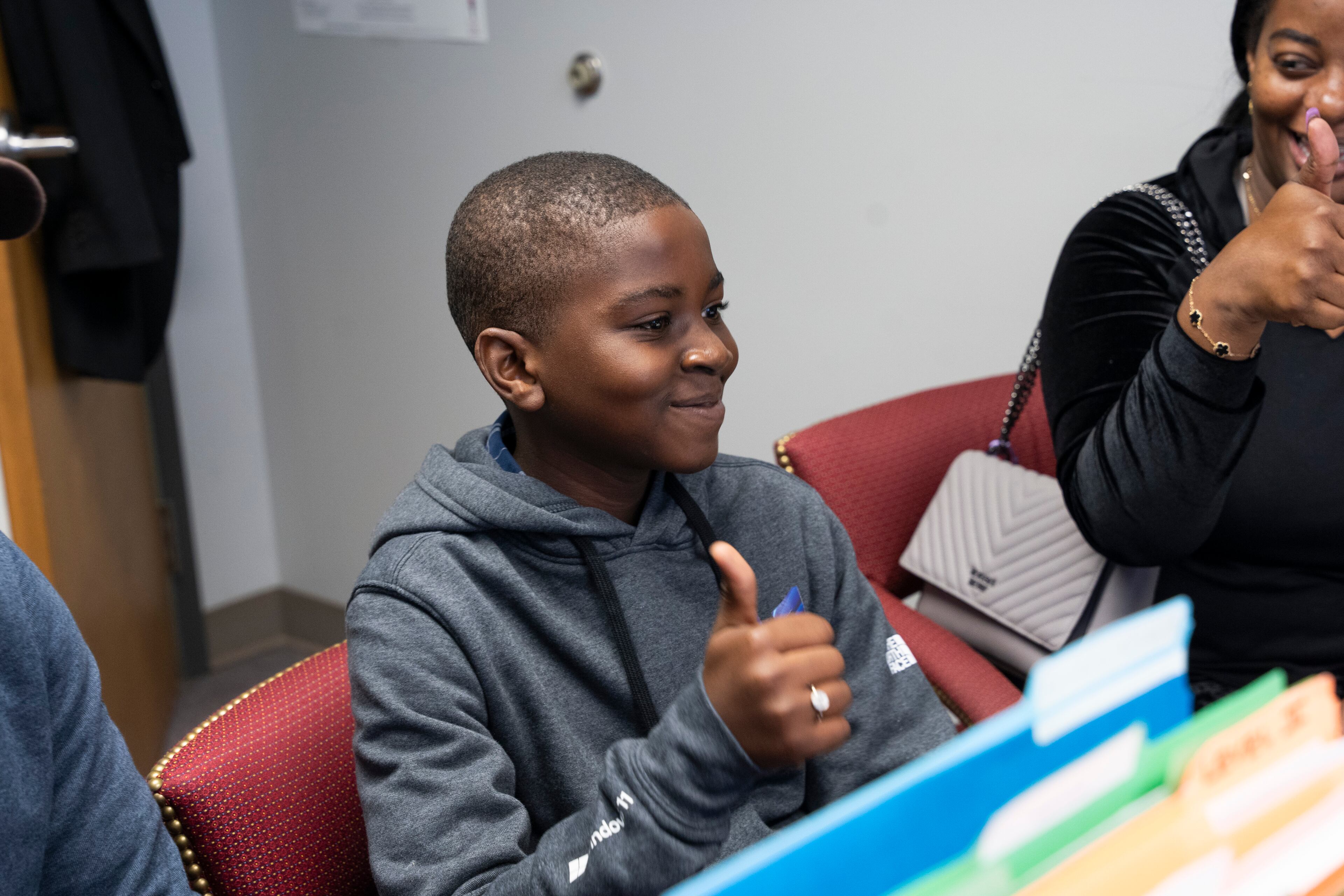

Mandeng visited the center in early October with his 11-year-old son Nathan after a week in Gwinnett and about 10 years of trying to immigrate to the U.S. from Cameroon. Mandeng’s sister, Lynda, came to the country about a decade ago. Mandeng’s mother preceded him in moving to the U.S. He hopes to bring his daughter and fiancee as well.

Most of Mandeng’s meeting with international student adviser Joseph Ruiz was conducted in English, with Lynda Mandeng translating to French as needed.

Toward the end of the visit, Mandeng noticed a parenting book about raising emotionally strong boys on Ruiz’s bookshelf.

“May I borrow that?” he asked.

Ruiz did better.

“You can have it. I’ve already read it,” he said, even adding a welcome inscription on the title page.

Mandeng said he enjoyed spending time out and about, taking in the greenery and having surprise encounters with squirrels and deer. He’s also appreciated the friendliness he’s found, both in the center and in the community. He liked how people often greet each other in passing and said Nathan’s already been playing with kids in the neighborhood, regardless of language barrier.

Ruiz didn’t worry about language differences either. He helped Nathan get ready for his assessments and assured him it was fine if there was anything he couldn’t answer: “Don’t worry. We’re going to teach you everything you need to know.”

Continuing coverage

One-third of students in Gwinnett County’s school system are Hispanic, the largest demographic in the district. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution is taking a closer look this school year about how Gwinnett is addressing the ongoing increase in its Hispanic student enrollment and the challenges they face educating those students.