Anti-maskers storming Georgia school board meetings argue that forcing students to wear a face covering infringes on the children’s “liberty and freedom.”

Have they ever read their school dress codes?

Parents hoisting “My child, my choice” signs either don’t know or don’t care about school dress codes that penalize 5-year-olds for spaghetti straps that reveal too much shoulder or 11-year-olds for T-shirts that expose midriffs.

For example, Wilcox County Schools encourages masks but doesn’t mandate parents send their kids to school with them. However, its dress code for the upcoming homecoming dance sets several rules for teenage girls, including no high slits or sheer material. And, in an unusual regulation, the district insists on prior school approval of dresses, instructing students to submit a photo of themselves in their dress.

All the Southern governors bellowing that schools can’t mandate masks because parents have the sole authority to decide what their children wear to school may have created a template to challenge school dress codes. A Chattanooga mom became a social media hero with her note last week to the school board there explaining that since Tennessee declared that parents could opt out of mask requirements, “I can only assume that parents are now in a position to pick and choose the school policies to which their child is to be subject. ... I therefore intend to ... send my daughter to school in spaghetti straps, leggings, cut offs, and anything else she feels comfortable wearing to school.”

(In a work-around, Texas school districts are circumventing Gov. Greg Abbott’s executive order banning mask mandates by adding masks to their school dress codes.)

Schools can offer a sound rationale for insisting kids wear masks: The masks save lives by preventing the spread of a dangerous virus.

What defense is there for dress codes that stipulate “2-inch minimum strap on each shoulder”?

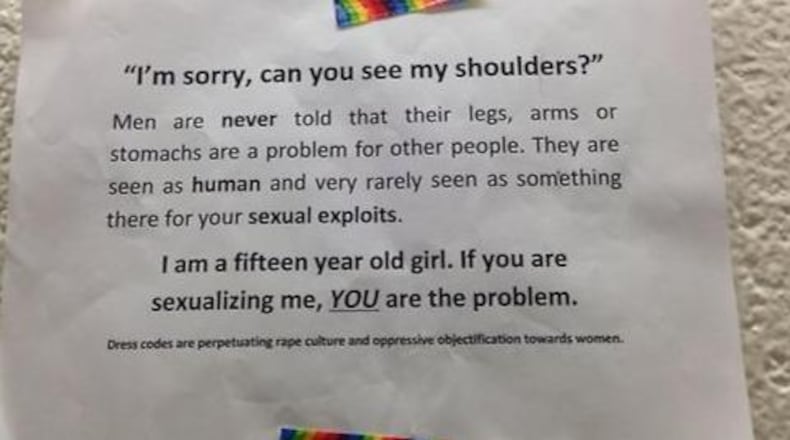

The standard argument has been female skin distracts male students, but girls, bolstered by the #MeToo movement, are shutting down that argument, adopting the messaging “I am not a distraction” and telling school boards they are not responsible for what boys think.

A current Change.org petition targeting Fayette County’s rule on shorts for girls was launched by a graduate who says her younger sister came home from her first day of school crying “because the outfit we picked out together the night before for her big day was dress coded and she was made to change and felt inappropriate and embarrassed. She was wearing soccer shorts.”

The Fayette dress code states, “Skirts, dresses or shorts hems must be at or below the fingertips or mid-thigh.” This fingertips rule is common and routinely lamented by parents who contend that the authors of school dress codes apparently have never shopped for back-to-school clothes for girls. If they did, the parents maintain they’d find few shorts that meet the fingertips test.

Atlanta therapist and parent Amy Bryant worries about the impact of dress codes on the stress levels of parents and children. “A lot of parents are talking about how much time they have had to spend finding clothes that fit dress code. They are saying that their kids are stressed out worrying about violating dress code,” she said.

Many families are worn out after a year of learning amid a pandemic. Schools should be welcoming to returning students, not adding to their stress, Bryant said.

Bryant understands dress codes are seen as a way to impose order, but says, “From the first day of school, my daughter came home and said adults were yelling at all the kids in the hallway about dress code violations. Kids are being called out of class. They are missing class. They are sent home. That is chaotic and there is nothing helpful about that to students.”

Bryant, who is organizing like-minded parents to promote equitable dress codes, believes stringent limits on what kids can and cannot wear deliver destructive messages about conformity and control. Dress codes, which typically come down hardest on middle school girls, penalize students for body size and body maturity.

For a better way, Bryant cites the dress policy enacted in Toronto schools in 2019, which incorporates three tenets: The primary responsibility for a student’s attire resides with the student and their parents or guardians. Students have the right to express themselves, feel comfortable in what they wear and the freedom to make dress choices (e.g., clothing, hairstyle, makeup, jewelry, etc.). Students have the responsibility to respect the rights of others and support a positive, safe and shared environment.

The Toronto policy earned the endorsement of educators, who were tired of being hemline police. The policy imposes a few rules; it states, “All bottom layers cover groin and buttocks and top layers cover nipples, both with opaque material.” Nor can students wear undergarments as outerwear, but undergarment straps and waistbands can show. Schools must treat dress code violations as “minor on the continuum of school rule violations.”

American schools have long micromanaged what children can and can’t wear. In the 2017-18 school year, 42.6% of elementary schools, 61.6% of middle schools and 55.9% of high schools reported they enforced a strict dress code for their students, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Students have been fighting dress codes for decades. Cobb eighth grader Sophia Trevino is leading the fight in her school after she and 16 other females were cited on the first day of school, causing them to miss their first class. (Her transgression was a hole in her jeans.)

“The school talks about empowering women,” says the 13-year-old, but then undermines the education of girls by “pulling them out of class because of a hole in the knee of their jeans.” Every Friday, her classmates wear T-shirts Sophia has been making that point out dress codes are sexist, classist and racist.

Sophia also launched a petition to change the rules, which has garnered more than 700 signatures. She plans on attending an upcoming school board meeting to point out more progressive and inclusive dress codes that Cobb could emulate. Many classmates and even some teachers have endorsed her effort. “But some people have said it’s not a problem,” Sophia said. “Most of them are boys.”

And it’s not a problem for boys. Historically, school dress codes target girls. An analysis of dress codes in Washington, D.C., public high schools by the National Women’s Law Center found the rules still largely fall on female students, especially students of color, with their focus on skirt and shorts length, bare midriffs, exposed shoulders and too-tight pants.

Earlier this month, a three-judge panel for the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Title IX, the federal law outlawing sex discrimination in schools, may extend to dress codes that are discriminatory. The case was brought by parents upset with a sex-specific dress code at a North Carolina charter school requiring girls wear skirts as part of its “traditional values.”

A school leader said the skirt requirement furthered “chivalry,” which meant “a code of conduct where women are ... regarded as a fragile vessel that men are supposed to take care of and honor.” The federal appeals panel sent the case back to federal district court.

A recent act of defiance by Norway’s women’s beach handball team drew attention to the incoherent and sexualized basis of dress codes. The handball team was censured by the European Handball Federation not for showing too much skin, but too little. The team competed in shorts rather than the mandated skimpy bikini bottoms seen as an attendance lure. Male players can wear shorts.

Women worldwide rallied around the Norwegian athletes, including pop star Pink, who tweeted: “I’m very proud of the Norwegian female beach handball team for protesting the very sexist rules about their uniform. The European Handball Federation should be fined for sexism. Good on ya, ladies. I’ll be happy to pay your fines for you. Keep it up.”

About the Author