Opinion: Starting small might aid Gwinnett’s school discipline shift

Educator Peter Smagorinsky retired from the University of Georgia at the end of 2020. His book, “Learning to Teach English and the Language Arts,” was awarded the 2022 Exemplary Research in Teaching and Teacher Education Award from the American Educational Research Association.

In this guest column, Smagorinsky dives into the discipline debate roiling Gwinnett County Public Schools.

By Peter Smagorinsky

Gwinnett County is currently in an uproar over “restorative justice” approaches to student discipline. Restorative justice, as advocated by one set of Get Schooled contributors, advocates for empathic and relationship-building approaches to addressing violence in schools. In contrast, restorative justice is viewed as soft and ineffective by what I’ll call the law-and-order approach. This perspective views punishment as the best way to teach kids how to manage their behavior and protect others from violent consequences.

Both the law-and-order and restorative justice approaches originated in the criminal justice system. Law-and-order advocates believe that they are preventing criminal lives from developing by punishing errant youth and teaching them how to act right, while also removing menacing students from classrooms.

Restorative justice advocates see a school-to-prison pipeline being built when students’ problems with relationships are treated as crimes that produce the equivalent of a “rap sheet” (Record of Arrests and Prosecutions) in their teens. Restorative justice assumes that creating a criminal past during youth is too great a penalty for an outburst; that an education should include more than the Three R’s. It should work to teach young people how to engage with others productively and nonviolently, through empathy, relationship-building and community-building.

My thoughts on this question don’t lead me to take sides on this polarizing question leading to polarized options. The last thing teachers and schools need is another outsider telling them what’s best. Especially when nobody really knows what’s best.

Law-and-order responses to disruptions are surely the simplest approach to discipline issues. Be bad, be punished. Rules are rules. Break them and pay the price. Break them again and get suspended, and possibly expelled. Such an approach is designed to make schools free of troublemakers and more likely to promote a conducive learning environment.

Unfortunately, some students are more likely to be viewed as troublemakers than others, as any school discipline statistics will easily reveal. Racial disparities and disability status data show that being an able-bodied, able-minded white student produces more generous interpretations of conduct than being a student of color or one struggling with a mental imbalance. A key premise of the law-and-order stance, then, assumes that justice is colorblind. But you’d have to ignore all statistics collected on the matter to accept this axiom.

But restorative justice has its own issues. One problem is that it’s more a set of values and understandings than a clear action plan. Its elements are interpreted and put into practice locally. Restorative justice seeks to help students find reasons to get along better, rather than imposing rules on them from above. There are some structural features — facilitators, small groups — but no single way to use them. It’s hard to say if something “works” when it inevitably varies in implementation.

Another issue in restorative justice, and I think one of its greatest challenges, is that it relies heavily on buy-in from all stakeholders. People who don’t believe that taking a “social-work” approach to discipline will either improve behavior or make schools safer will undermine the program. And in my experience, there are no schools in which the whole administration and faculty believe that punishment is ineffective and that conflict-resolution conversations will redirect students’ trajectories toward better citizenship. Meanwhile, many people in schools are cynical enough to think that students will quickly learn how to manipulate the system so that they go through restorative motions without changing how they think, feel and act.

Restorative justice thus has an idealism that may compromise its success. But law-and-order may rely on its own questionable foundations. Critics of restorative justice have argued that the recent rise in school violence follows from soft restorative justice interventions that kids don’t take seriously. Rather, it seems clear that the COVID era has made schools and society far more violent than they were before the shutdown, which has caused setbacks in socialization. Blaming the solution for the cause strikes me as inattentive to what the news reports on a daily basis: Society as a whole has gotten far more violent since 2020.

We therefore have a societal problem manifesting itself in schools, with near-identical disagreements about how to solve it in either setting. Do I have the solution? Not really. But I do recommend an approach that defies much administrative thinking. The Holy Grail of educational reform is the prospect of “taking to scale” a new program. But programs implemented from the top down rarely have that critical buy-in and tend to flop. New educational ideas tend to be so idealistic that they inevitably fail, and among the ideals is that something brand-new can succeed as planned on paper.

These innovations fail in part because they are conceived and imposed from outside the input of the people charged with implementing them. When school staff members are told that everything they’ve always done must change right now in the opposite direction, the very people upon whose actions the program’s success depends may misunderstand it, work against it, or make it a low priority. The more massive the institution, the less likely a massive change will work. And Gwinnett County is immense, enrolling more than 40,000 more students than does the state of Rhode Island.

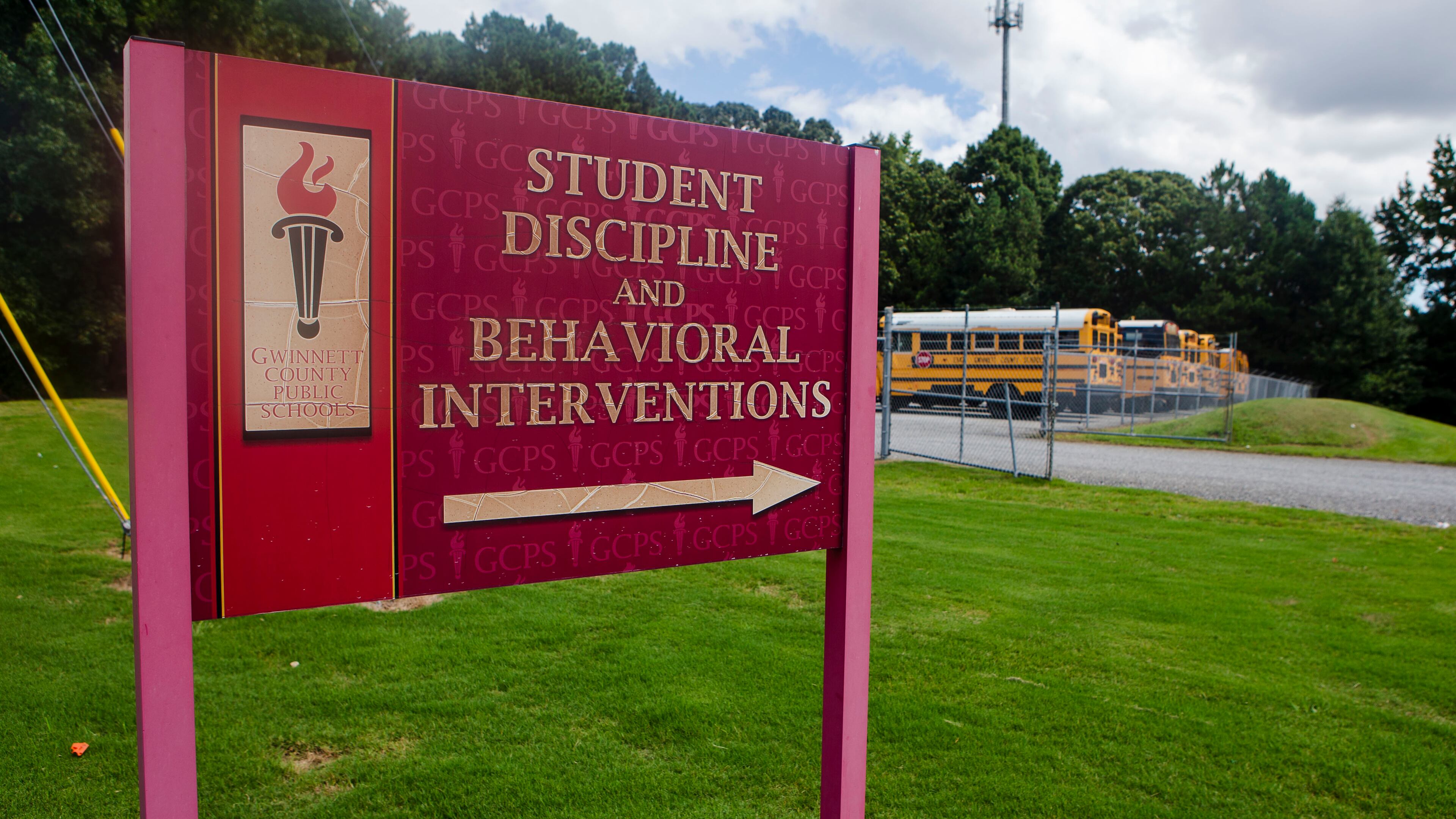

My suggestion requires a lot more patience and piloting. If buy-in really matters — and it always does — start small with people who are interested in seeing how it works. Gwinnett County has a school police department with full police powers, the opposite culture of what restorative justice seeks to develop. Going straight to scale with restorative justice seems doomed from the beginning when the institution’s structure is predicated on law-and-order.

But among the 142 schools in the district, there might be places where there’s belief in its possibilities. I think that’s where you start: with people willing to give it a good try and evaluate the consequences. Pilot the program where it has a chance of succeeding and see if it works such that others want to implement it. If they don’t, it won’t work anyhow.

Start small with volunteers, pilot and evaluate the program, see if it’s amenable to expansion; and if not, figure out why and agree on what to do next. It takes a patient administrator to give that process a try, and in a society that demands overnight results, such possibilities are limited. But since a rushed imposition of a program will likely fail anyhow and cost people their jobs, perhaps it’s worth trying.