Opinion: More Georgians get education after high school but not enough

Today, nearly 54% of working-age Americans hold college degrees, college-level certificates or industry recognized credentials. It’s still not enough to meet rising workforce demands of a knowledge-based economy, especially in Georgia, which trails the national average for educational attainment after high school.

In Georgia, only 51% of adults ages 25 to 64 hold college degrees or other credentials of value, according to the Lumina Foundation, which tracks education and training beyond high school using data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. The foundation just updated its online tracking tool, Stronger Nation, with 2021 data.

While Georgia may lag the nation, it saw growth in working adults with bachelor’s and graduate degrees in the Stronger Nation analysis. In 2019, 21.3 % of Georgia adults held a bachelor’s degree and 12.7% had a graduate or professional degree. In 2021, the percent with a bachelor’s rose to 22.1% and those holding graduate degrees and beyond climbed to 13.8%. Georgia did see a dip in adults earning short-term industry credentials, likely because the pandemic decreased enrollment in technical school programs.

Of the 171 million jobs projected in the United States by 2031, 30% will be available to high school graduates, another 30% will demand middle skills, defined as more than high school and less than a bachelor’s degree, and 40% will go to those with bachelor’s or graduate degrees, according to the Georgetown Center.

That’s why so many states are seeking to entice more high school graduates into higher education or training programs. “None of this is an overnight fix,” said Courtney Brown, vice president of strategic impact and planning at Lumina and director of the Stronger Nation project.

Georgetown has done extensive research on how education affects the ability to secure a good job, defined as one that pays at least $35,000 for younger workers and at least $45,000 for those in mid-career. At age 35, 80% of young workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher have a good job, as do 56% of young workers with some college or an associate’s degree. Among 35-year-old workers with no more than a high school diploma, 42% have a good job, and for workers who never completed high school, that share is 26%.

The state Senate Committee on Government Oversight last week advanced a bill designed to increase access to good jobs, at least those in government. Senate Bill 3 calls for an inventory of state jobs for which the educational, experiential and training requirements could be lowered. The bill, which passed the Senate 49-1 on Thursday and went to the House for more debate, seeks a reduction in jobs requiring a four-year college degree.

“What we found over time is things have changed,” said bill sponsor Sen. John Albers, R-Roswell, during the hearing. “Where we used to mandate a college degree for everything, now we’re looking at it differently through either a technical school or a certification.”

“If there was a technology job that required a bachelor’s degree and 10 years’ experience, sometimes that technology was only created two or three years ago so you couldn’t have 10 years’ experience. But someone might think I can’t apply,” said Albers, explaining the rationale for the legislation. “As an example, Bill Gates would be unqualified for that job. He never graduated from college, but arguably he is one of the most successful people in technology that has ever walked God’s green earth.”

The struggle to find workers has already led Pennsylvania, Maryland and Utah to slash the number of state jobs calling for a college degree. Those states believe talent can come from technical schools, apprenticeships, military service, workplace experience and certificate programs. And that is true, although a college education provides a skill set increasingly vital in a job market that demands adaptation and reinvention.

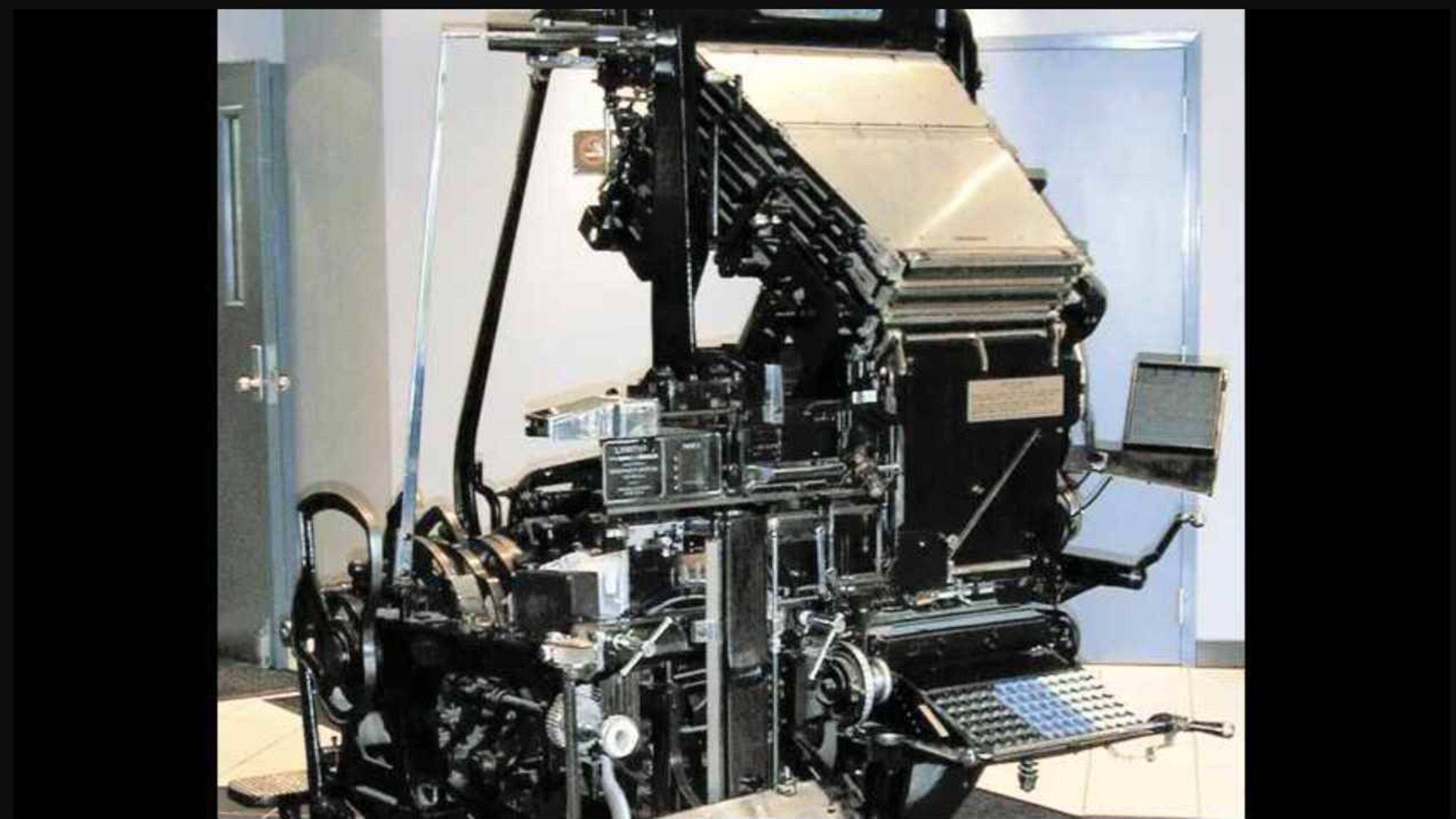

Higher education teaches people how to research and learn and think critically, abilities that can fend off knowledge obsolescence. Too often, industry-specific credentials serve a narrow focus, training workers to perform narrow tasks reliably. The problem comes when those narrow tasks become obsolete. Baby boomers who earned Wang Word processing certifications can now hang them alongside other historical family artifacts like their grandfather’s Linotype machinist credentials.

As in the state Senate hearing, Gates is often held up as proof that college isn’t necessary to succeed, but the Microsoft co-founder has long encouraged young people — including his own three children — to complete college and donated a considerable share of his fortune to education initiatives.

Gates has explained he only dropped out of Harvard because he was racing against the clock to be an early innovator in the fledgling computer software field, telling an interviewer a few years ago, “Unless you have something uniquely, amazingly time-dependent, it’s great to finish the degree.”