Educator Peter Smagorinsky retired from the University of Georgia at the end of 2020. His book, “Learning to Teach English and the Language Arts,” was awarded the 2022 Exemplary Research in Teaching and Teacher Education Award from the American Educational Research Association.

In this essay, Smagorinsky explains why schools don’t relate to children of color, who are fast becoming the majority of public school students in Georgia.

By Peter Smagorinsky

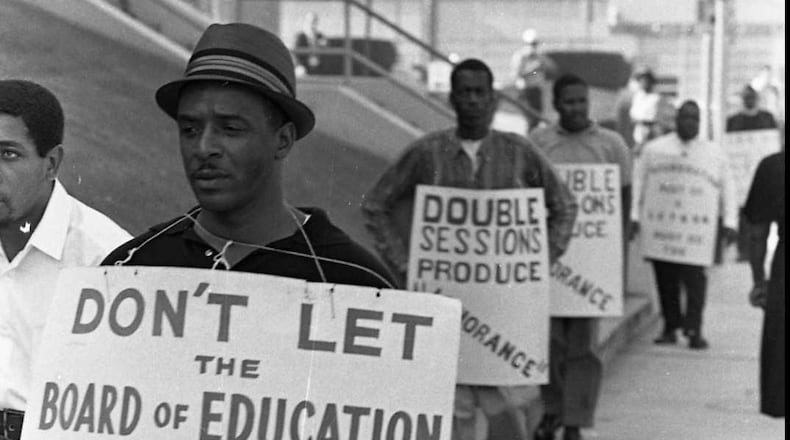

The AJC Get Schooled blog has recently published essays by Atlanta-area high school students in which they provide their perspective on the state of education. These smart young adults have done something their teachers are prohibited from doing: They are speaking out against the injustices they have experienced in Georgia schools, injustices denied by the adults who are trying to influence schools to be silent on matters of racism.

I was once a white kid in school, and for much of my education, we were legally segregated from Black kids. We studied a version of history that I think many people would love to see restored. Here is an excerpt from a Virginia history textbook from my schoolboy days in the 1950s and 1960s:

“Life among the Negroes of Virginia in slavery times was generally happy. The Negroes went about in a cheerful manner making a living for themselves and for those for whom they worked. … They were not worried by the furious arguments going on between Northerners and Southerners over what should be done with them. … The Negroes remained loyal to their white mistresses even after President Lincoln promised in his Emancipation Proclamation that the slaves would be freed.”

When you study this sort of thing in school, when it’s written in a history book and impressed on you by your teacher, such myths tend to become ingrained in the mind as the truth. This version of history then becomes naturalized as the established narrative of the past. Challenging it is often called “revisionist history.”

Yet, it was revisionist itself, a post hoc narrative designed to cover up the truth. It was the rare occasion when the losers wrote history. It remains the story that stands, that is being challenged, and that is now defended with more furious arguments about what to do with history in schools.

There’s an old aphorism in another nation now in the news: Nothing is more unpredictable than Russia’s past. Rewriting Russian history occurs every time there is a need to justify the present. It’s happened often before and is happening again in Russia. It’s happening in the United States, as well, with the version of Southern history created by the Daughters of the Confederacy that was inscribed in my schoolboy textbooks still influencing how people see race in this country.

It’s not as absurd as the versions of history I read in my schoolboy days. But the idea that there is no racism in the United States, widely and emphatically propagated by politicians and citizens and school boards, strikes me as fantastical.

An essay by North Gwinnett High School student Adunni Noibi gets at why. She points to many instances of racism she has experienced as a student and citizen. The evidence of national and educational racism is overwhelming. Yet people still deny that it exists at all, and insist that the real victims these days are white kids who might feel bad if they learn the truth.

The first time I attended schools with someone who wasn’t white was when my family moved to New Jersey in 1968, halfway through high school. Fairfax County had integrated its schools when I was in seventh grade, but my high school put most of the Black kids in special education and out of my mainstream classes.

I had to relearn a lot by listening to people talk about their experiences, by reading books by Black authors for the first time, by questioning the validity of what I’d been taught in school. It was an education about education, and it wasn’t always easy. There was a lot of anger then, just as there is a lot of anger now when it comes to whose stories are worth listening to.

It also matters who is in authority in deciding what can and can’t be talked about in school. Schools are very white places. About 80% of public school teachers are white, 78% of school principals identify as white, and 78% of school board members are white. U.S. schools were founded on the principle of assimilation to norms, with Normal Schools given the task of training teachers to enforce those norms. It’s easy to see whose values govern life in schools, and in society as well.

Noibi asserts that “when none of my teachers look like me, that’s racism.” I would like to add nuance to this belief. I worked in teacher education from 1990-2020 and taught very few students of color at two universities, Oklahoma and the University of Georgia. Consistent with national numbers, at least 80% of my students where white, probably a good many more. Districts can’t hire people who don’t want to be teachers and who don’t enroll in teacher education programs. They hire who’s available, and that’s mostly white people.

Meanwhile, there are annual appeals to recruit, train, and hire more teachers of color. Yet, the numbers remain very steady at about 80% for school personnel.

Schools were founded by white people for assimilation in the mid-1800s. They have been overwhelmingly staffed by white people teaching textbooks written by white people for much of the nation’s history. They operate in ways that fit white people better than people socialized through other traditions. Although plenty of white kids feel out of sorts in school, it’s nothing like the way students of color feel. Just ask Noibi, who by all accounts is a conscientious student yet finds school to be an alienating place, a not uncommon situation.

If a population of people feels like Adunni, then what are the chances they’ll want to invest in teacher education and then spend many decades working in schools? Here is how she describes her education: “I go to school in a place where plantations once stood, where monuments to Confederate leaders and slaveowners still stand. I didn’t have a school board that looked like me until last year.”

Her account resonates with what I found in my research: People who feel disaffected in and rejected by schools don’t want to go back and work in them. You can’t treat students of color like second-class citizens and then complain that schools don’t have enough teachers from their backgrounds. If you want to keep the teaching force white, don’t touch a thing in schools. They’re set up for reproduction and assimilation, not interrogation and change.

The current times are not promising as prohibitions against teaching the truth about race proliferate. I’m heartened to see the kids leading the protests against these suffocating efforts, something their teachers can’t do without risking their careers. For them to have an impact, the adults need to show that they respect their views and can listen and learn. We’re all still waiting for that to happen.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured