Georgia schools: More guns, more shootings, more security measures

Guns in Georgia’s public schools are on the rise.

So, too, is the debate about what to do about it.

The fall semester started with clear backpacks in some places and long security lines in others. Meanwhile, officials are pledging to spend more money on everything from more armed officers to newer, high-tech scanners and license plate readers.

But there’s still little consensus about what works and what doesn’t — and how far security measures should go.

North Atlanta High School in Buckhead, for instance, reverted to random weapons screening after long lines formed when every student was scanned. Matan Berg, a senior there, said the debate team explored how an armed student could evade the system. Berg noted his bag got only a cursory search when he got scanned.

“There’s so many loopholes,” he said. “This is not a shot at my principal in any way. It’s just, like, the reality of the situation.”

Matan and his mom were among a couple of dozen people attending a recent safety forum at an Atlanta middle school in Buckhead. Some said the security was intrusive, including a mom who complained about students standing in the rain at a middle school during a weapons check bottleneck. She wanted newer equipment. Another mother wanted more police stationed around her elementary school in the morning and afternoon when children are coming and going.

The efforts by local school districts to implement additional security measures are in part a reaction to high-profile incidents, such as the mass murder at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, at the end of last school year. The most recent action took place Tuesday, when Atlanta’s school board approved a plan estimated to cost $2.6 million to install more advanced weapons screeners in middle and high schools.

There are more guns, and shootings, in Georgia’s schools than in the past, according to official records and media reports. During the school year that ended in 2015, there were 76 incidents in which a student was disciplined for bringing a handgun to school, according to Georgia Department of Education data. By last year, new data reviewed by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution shows the number of handgun cases had nearly tripled, to 195. Counting rifles and other firearms, the number rose to 293.

Atlanta Public Schools Police Chief Ron Applin told Matan, his mom and other parents who attended that safety forum in Buckhead that school officials have been confiscating more weapons lately. There were 34 disciplinary cases for a firearm in Atlanta Public Schools in the last academic year, the second-highest in the state after DeKalb County, which had 55. The APS total is up from 15 in the 2014-15 school year.

Applin urged parents to help by snooping on their own kids — eavesdropping on their phones, rifling through their book bags and rummaging their bedrooms.

“The best response to an active shooter is to prevent it,” he said, adding that research has found that in most cases someone besides the shooter knew a mass shooting was imminent. “Safety is not just the responsibility of the police. It’s everybody’s responsibility.”

State School Superintendent Richard Woods believes the rising weapons tally is a sign of success, in part with the help of students informing authorities on their peers — their sense of self-preservation perhaps outweighing what once was seen as a stigma.

“I think we’re doing a better job of finding things,” he said in an interview.

Even so, the presence of weapons isn’t the only risk: More people are discharging them on school grounds.

Everytown for Gun Safety compiles press reports of gunfire on college and K-12 campuses, and found incidents in Georgia nearly tripled from 2015 to 2021, when there were 13 campus shootings, with three injuries and one death.

One such incident occurred last March, when Atlanta schools police shot an armed mother outside Booker T. Washington High School. She had a child at the school and was brandishing a gun during a brawl, the AJC reported. An officer reportedly told her to drop the gun several times after she waved it at students. She was shot in the hand.

Searching for safety measures

Metro Atlanta school districts have had varied reactions to the concerns about safety.

Clayton County banned book bags last school year and followed this fall by requiring clear backpacks, supplying them at a cost of $1.1 million. “We saw a precipitous increase in weapons within a few months,” Morcease Beasley, the superintendent there, said in a press briefing before the fall semester.

Clayton also plans to spend $5 million on new weapons detection equipment for middle schools and high schools and for stadiums.

Rockdale County mandated clear backpacks, too, and Atlanta Public Schools has been talking about the idea.

Cobb County’s school board recently agreed to let some non-teaching staff carry weapons. DeKalb County has budgeted to add 22 armed officers to the school police force. Fulton County will use license plate cameras and exterior door alarms, and an advisory committee is expected to recommend how to allocate $6 million set aside for safety soon.

More extreme measures have been contemplated outside Georgia, from assault-style rifles in schools to Taser-wielding drones.

One company is pushing what it describes as U.S. Army-tested, quarter-inch thick, military-grade, heat-treated steel armor.

National Safety Shelters says its units — imagine ballistic-grade, human-sized lockers with vents, installed in classrooms — can resist handguns, shotguns, even weapons like an AK-47 or AR-15.

The shelters, which can be locked from the inside, are being sold by a company in Florida, not far from where a gunman slaughtered students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland in 2018.

“It is pathetic, I’ll admit this, that we actually have to do something like this to protect our kids,” said the company’s president, Dennis Corrado.

The best lines of defense

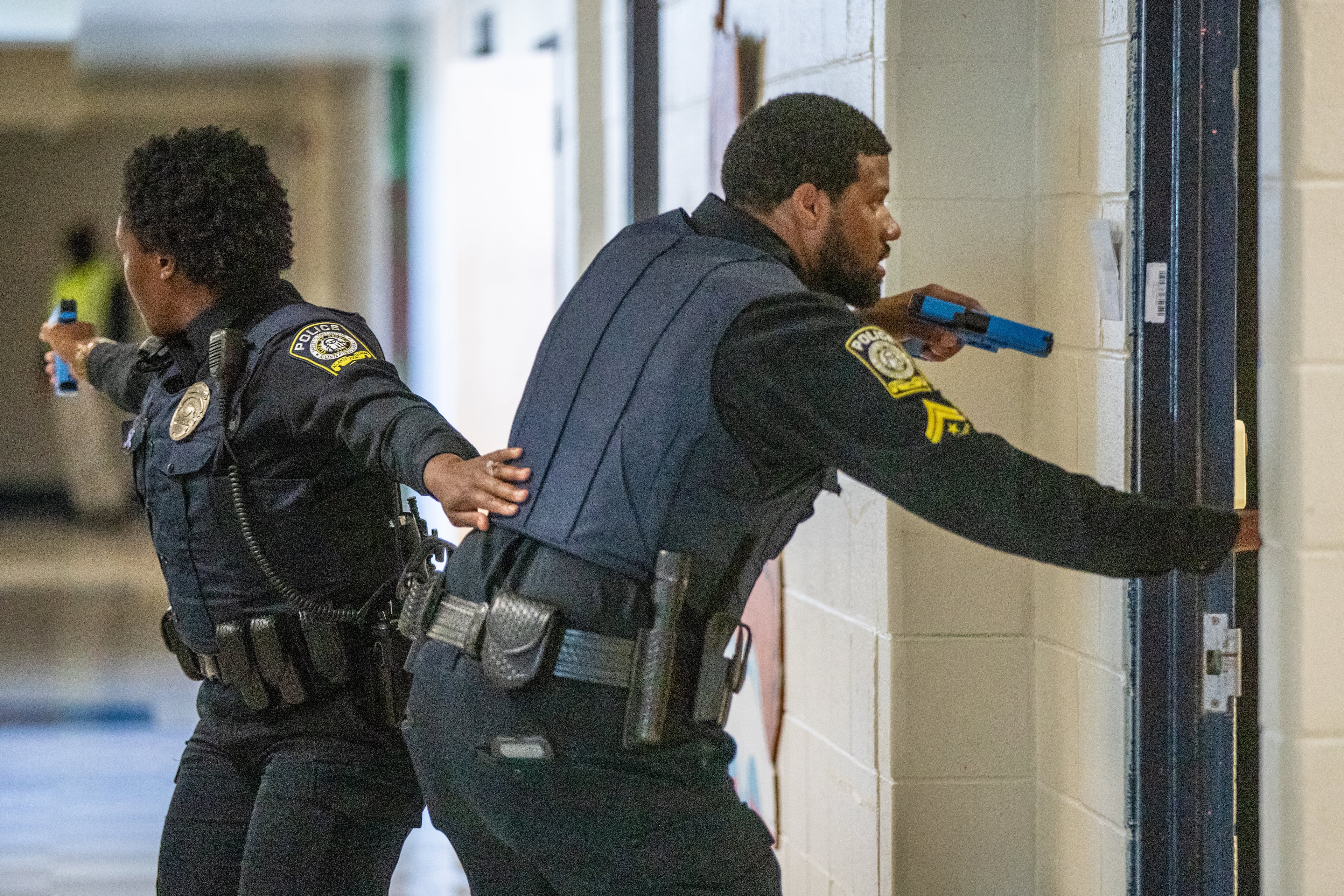

Applin, the Atlanta schools police chief, said during a late-July training exercise for his officers that he thought such shelters would be too complicated in a hectic situation. The most he hoped teachers could do is pull the classroom door shut and lock it. He said he plans to add nearly a dozen officers to his force, bringing the total to over 100.

One of them will be a gang intelligence officer who can devise a response to the more than 33 gangs in the city’s schools. “Gangs are represented in every school in our district,” Applin told parents at that Buckhead safety forum.

Applin said he also wants to hire a social-emotional learning expert who can intervene before an interaction between student and officer results in a criminal charge.

A study by researchers at University at Albany in New York and the Rand Corp. found a tradeoff with school police. They reduce violence but not gun-related incidents; meanwhile, they increase disciplinary reactions, such as suspensions, expulsions and arrests, especially with Black students and students with disabilities, said the report, “The Thin Blue Line in Schools.”

Thaddeus Johnson, a cop-turned-academic who teaches criminology at Georgia State University, said there is a role for police in schools, but he said schools should be investing more in “therapeutic” intervention. They need counselors and teachers trained to deal with trauma as much or more than they need metal detectors, he said.

Some of these expenditures make students and their parents feel safe, he said, without necessarily increasing safety. “The real question is not how many weapons we find in schools. The real question is why do kids feel the need to bring weapons to school,” he said, noting that the most dangerous time of day for many kids is between school and when their parents get home from work.

“It’s because they’ve got to protect themselves,” Johnson said. “I grew up in south Memphis, right. You’ve got to carry something because you have to protect yourself ... because you don’t necessarily believe the police can protect you ... or you’re just not confident in the police or just in government in general.”

Karen Kerness, the mother of Matan, that North Atlanta High student who expressed concern about weapons scanners, said she doesn’t fault teachers or school administrators.

“No school has the money to fund the level of advanced technology we need to deter all of the loopholes that are out there,” she said.

Some teachers think the safety concerns are overblown. Brandon Wyatt, a language teacher at Ashford Park Elementary School in DeKalb, said it’s easy to “doom-scroll” bad news on a phone and lose sight of the big picture. “But when sitting back, taking a logical look at it and looking at the statistics,” he said, “honestly it feels like you’re more likely to be struck by lightning than you are to be involved in a mass shooting.”

But Antoinette Tuff, a school bookkeeper in DeKalb, sees a risk of more violence as traumatized children emerge from the pandemic, some having lost a parent. They need intervention, and she said support staff like bus drivers and cafeteria workers know what’s happening with kids because they talk with them, yet these support staff aren’t often included in administrative decisions.

“They’re not understanding what we are dealing with on the front lines sitting in these schools,” said Tuff, who talked a shooter into dropping his AK-47 after he fired it repeatedly on the grounds of Ronald E. McNair Discovery Learning Academy in 2013. “I think when you get back to that and start putting people in these meetings and allowing their voices to be heard, you’re going to see something different.”

Peter McKnight, the head of Drew Charter School in Atlanta, said some of his staff were concerned about reopening this fall due to the “pace and quantity” of shootings. They train for safety, but he said his first line of defense is social and emotional: offer support for students so they don’t lash out with a weapon, and cultivate relationships with students and families so they report suspicious behavior.

“The supports that exist around your students and your families are going to be the best line of defense,” McKnight said.

“But,” he added, “I think we’re at a point where that shouldn’t be your only line of defense.”

Staff writers Cassidy Alexander and Vanessa McCray contributed to this article.

WEAPONS IN SCHOOLS

Here’s how many times school officials say a student was disciplined for bringing a handgun, rifle or other firearm to school in some of metro Atlanta’s largest school districts during the 2021-22 school year.

District Firearms Cases

Atlanta 34

Cherokee 1

Clayton 25

Cobb 14

DeKalb 55

Forsyth 0

Fulton 30

Gwinnett 8

Source: Georgia Department of Education