Politicians enter fray on best way to teach Georgia kids to read

In the constantly shifting world of academia, there’s a long-running debate over the best way to teach children to read.

In one camp are educators who say reading is a natural skill that students learn mostly on their own. When children are read to, and their eyes follow each line, they get the knack of it, these experts say. If they get stumped, teachers guide them by encouraging them to consider surrounding words and pointing out clues on the page, such as pictures.

In the other camp are those who argue children need to be taught how letters interact to make sounds — that is, phonics. This type of rigorous reading instruction has worked for at least a century, they say.

This past legislative session, Georgia lawmakers picked a side in the decades-long feud, passing a measure that will require all school systems to adopt teaching materials that emphasize phonics.

But critics say the politicians are wading into a complex subject they know little about.

Legislators contend they are acting to address a crisis, one brought into focus by last spring’s statewide test scores.

“Right now, between 36 and 56% of our state’s kids are not reading on grade level when they finish third grade. That is a staggering number to me,” Rep. Bethany Ballard, R-Warner Robins told fellow lawmakers.

Sen. Billy Hickman, R-Statesboro, cited similar numbers while expressing worry about the future.

“We will never create an educated workforce if our children can’t read,” Hickman said.

In addition to requiring state approval of teaching materials, House Bill 538 by Ballard mandates frequent literacy testing of K-3 students and the retraining of teachers. And Senate Bill 211 by Hickman calls for the creation of a panel to review current practices and make recommendations to the legislature.

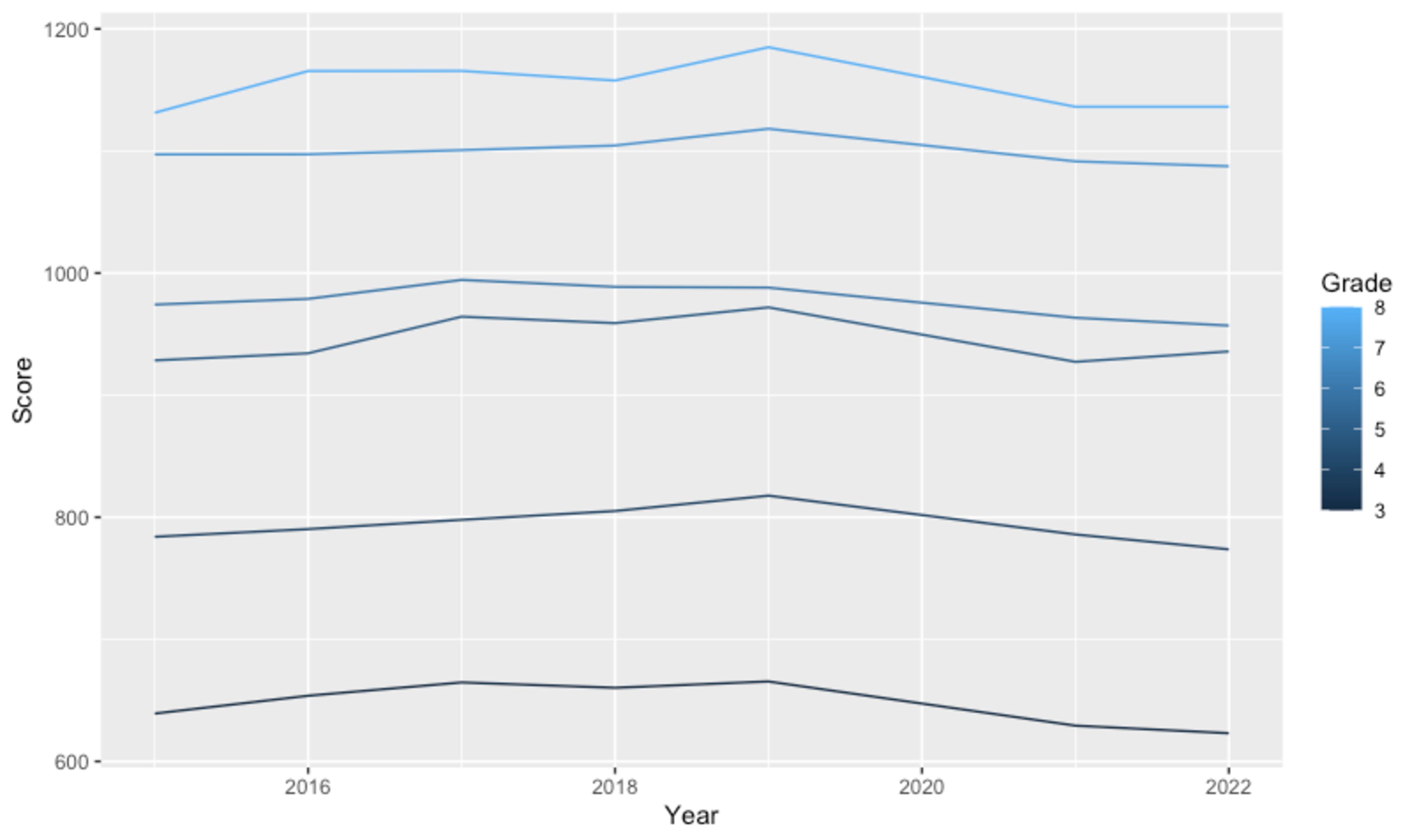

But some educators say claims of a crisis are overblown. Reading scores fell during the pandemic but have been relatively flat or rising over the decades, according to results on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, said literacy expert David Reinking.

He noted that Georgia is following numerous other states in adopting legislation under the banner of “science of reading,” which has become a movement.

That movement points to experiments done with magnetic resonance imaging — to examine the brain while a person reads — to bolster their argument that phonics is the best method for learning the skill.

But, while neuroscience may explain how people read, it doesn’t explain how to teach, said Reinking, who holds a courtesy post at the University of Georgia’s education college and is an emeritus education professor at Clemson University.

“You can’t just take the data and the information about the brain, and what it means, at face value,” Reinking said. “The study of the brain is in its infancy, and yet we’re making great leaps from that data and information to what we ought to be teaching kids.”

Even so, experts say there is plenty of research supporting phonics-based teaching. Indeed, on Thursday the Georgia Board of Education authorized new public school teaching standards for English Language Arts that were written to align with the new laws.

The Marietta way

It was reading time for Jennifer Brems’ first graders at Marietta’s A.L. Burruss Elementary, so the class broke up into small groups.

On that morning last winter, Brems had help from Katie Gaudette, a teaching coach.

Gaudette took a table with just four children, a rare luxury for public school teachers, who often must handle 20 or more students by themselves. She asked them a question: How many sounds are there in the word “sat?”

The boy to her left held up three figures, giving the correct answer. Per the rules of phonics, each letter in that word counts as one sound.

“Before science of reading, a lot of kids picked up reading because they just memorized a lot of words,” Brems said.

Some of her students didn’t know how to sound out words. Because of that, a few would get stuck on the same word for months, falling behind, she said.

She now has no doubt that systematically teaching the rules of phonics is the right approach.

Many are pointing to Marietta City Schools as a new model for literacy. Lawmakers invited the school system’s superintendent, Grant Rivera, to talk about literacy during this legislative session.

The tiny public school system, which has fewer than 9,000 students, is retraining teachers, rewriting curriculum and even sending staff into the community to help private preschool instructors learn about the science of reading.

The district has also poured money into personnel. It already had relatively small class sizes for reading when it put $7 million toward hiring another 40 reading specialists in January.

It will take time to determine whether Marietta’s new strategy is paying off. People will be watching to see whether the school system’s reading scores rise on the annual state Milestones tests.

Mississippi on the rise

In the meantime, Georgia lawmakers also point to Mississippi as a model.

That state adopted science of reading legislation in 2013, and its reading scores on that federal NAEP test rose quickly, closing the gap with the national average by 2019.

But Mississippi did a number of things the state of Georgia has not done yet: It put millions into helping schools implement the new approach. The money paid for literacy coaches, teacher training, student testing, read-at-home plans and reading camps.

Mississippi lawmakers also did something controversial. The law they passed prevents students from advancing to the next grade if they fail their reading test.

The state retained a tenth of its third graders after the 2018-19 school year, along with many students in the earlier grades. The most recent federal breakdown, for 2017-18, says the vast majority held back in second and third grade were Black.

Retained students get an extra year of teaching, and maturity, which could boost their performance on tests the next year, along with the state’s average scores. Also, scores were already rising before that 2013 law, though not always at the same pace.

“They’ve had steady progress for decades, which they should be commended for,” said Paul Thomas, a literacy expert. There hasn’t been adequate research to tease out the effect of phonics and related teaching methods from the other strategies employed by Mississippi, he added.

Thomas, an education professor at Furman University, noted that Mississippi’s eighth grade NAEP scores haven’t risen as much as those in fourth grade. “So whatever they’re doing doesn’t stick.”

He and other experts warn that phonics is no panacea.

Tim Shanahan, an emeritus professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, wrote in a blog post last winter that “plenty of kids” who adequately learn the skill still struggle with the ultimate goal of reading comprehension. Based on Shanahan’s analysis, Mississippi’s emphasis on phonics contributed only “incrementally or marginally” to reading scores after 2013.

More than a third of Mississippi fourth graders scored at the bottom of last year’s NAEP test, with 37% of them falling in the category called “below basic,” a couple percentage points better than the Georgia and national averages.

Children can grasp the “patterns” of words without explicitly being taught phonics, but a preponderance of evidence indicates more kids will get there more quickly if they are taught those rules, he said in an interview. While phonics won’t get all kids reading, he added, it’s better than memorizing words.

“This notion of ‘kids can’t learn to read without phonics’ isn’t true. You can learn to read without phonics — whole generations of kids have learned to read without phonics,” he said. “But fewer kids get there.”

__________________________________

Are you a Georgia parent or teacher or someone else affected by the state’s new direction with literacy? We’d like to know what you think of the changes and what you’re seeing in your schools now. Please also tell us if you’d like to be interviewed. Email us at: education@ajc.com

__________________________________