Does this bot care about you?

Emora is a freshman at a virtual university. She likes math and science, not so much history. She prefers one-on-one conversation, which is probably why she dreads giving presentations. Though she technically has no physical form, Emora likes to take walks at a nearby park and go to the movies.

Emora is not human, but she’s trying. She’s a chatbot designed to speak with people, in development by a team of Emory University students who hope it will help people with depression, anxiety or isolation.

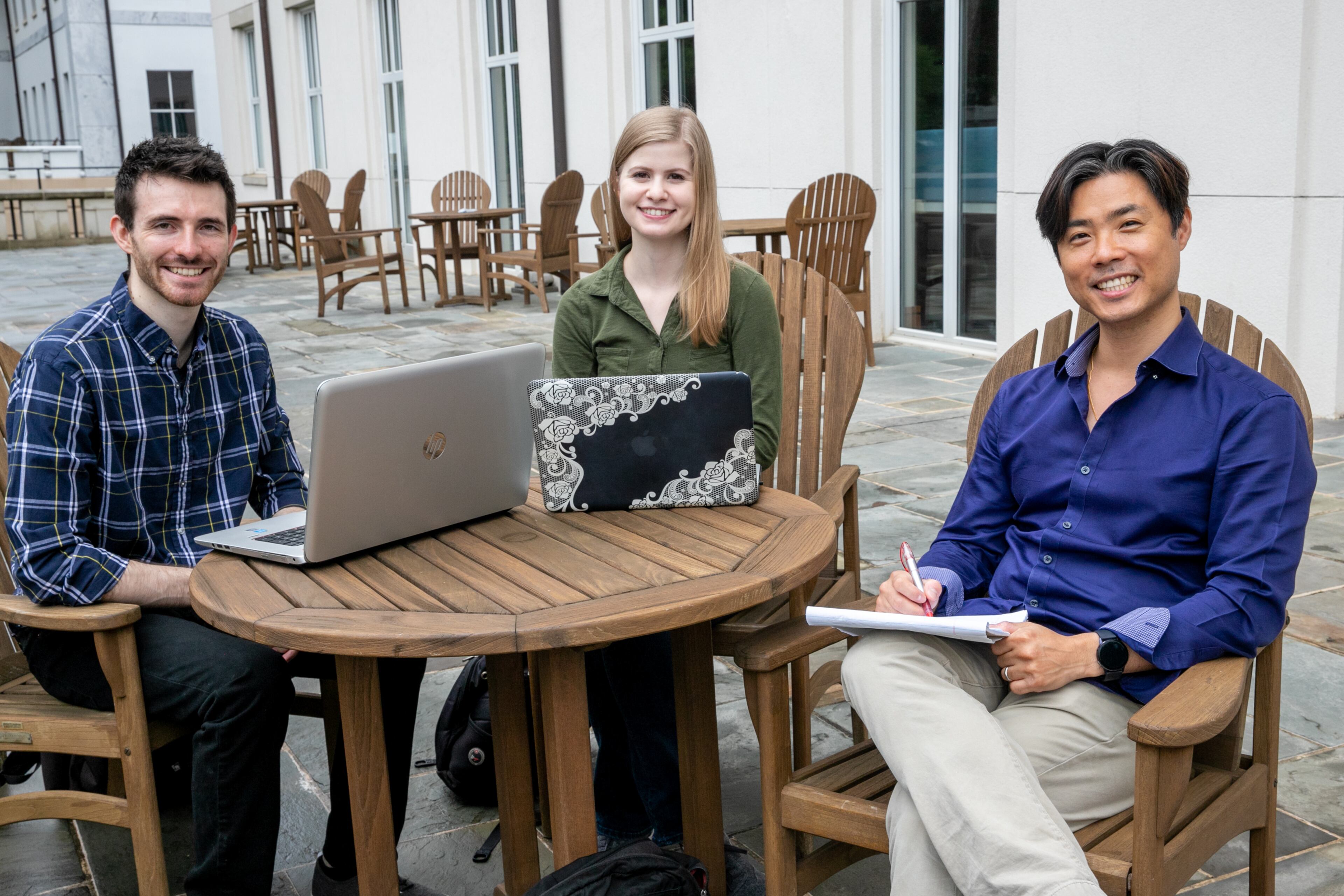

Computer science professor Jinho Choi, the imaginative and buoyant faculty advisor to the team, came up with the beginnings of the idea after worrying for his students with depression. Maybe, he thought, some would rather reveal their troubles to a computer.

A few years later, he and a team of students have won accolades and a $500,000 prize from Amazon for Emora.

The team sees Emora not as a stand-in for a person but a good alternative if a person isn’t an option, or a way to direct users to human professional contacts. The chatbot uses artificial intelligence and a pre-preprogrammed personal history to have complex conversations. Emora is being designed to operate through various devices including cell phones.

Chatbots have been in development since the 1960s, but even the most popular virtual companions on the market sometimes spew nonsense. The Emora team members hope they’ve found a combination of technology, skill and imagination to build a bot that can replicate a compassionate and helpful human with groundbreaking accuracy.

Their motto for the team: “Emora cares for you.”

Choi clarified, “It’s not like the bot is the one who is caring about you — it’s the people behind the bot. We want to use Emora as an opportunity to talk to the world and say, ‘There are people who care about you.’”

But Emora largely is the people behind her. They taught her who to be.

Until she started building herself.

A bot is born

Sarah and James Finch, the team leads, met at age 13 in math class and fell in love over computer code. The couple became fascinated by dialogue between humans and machines during their undergrad years at Michigan State University, where one class involved teaching a robot to fold T-shirts.

After arriving at Emory to study for their PhDs in 2019, they began working with Choi and found themselves becoming obsessed with conversation. The team was guided by research and intuition that told them the most engaging conversations are about the lives, opinions and experiences of those involved in the exchange.

Through late 2019 into 2020, the team of 14 students and Choi toiled side by side. Screens glowed with code. They’d turn to each other and talk about conversation: Would you ever say this? Why would you say that?

They read late into the night about how authors created characters and debated Emora’s backstory around a long table in a bland conference room.

Because characters need challenges, Emora has a tough assignment homework due tomorrow. She’s worried about what to give a friend for her birthday.

“If she’s always happy, then that’s kind of...,” James Finch said. “Hard to relate to,” Sarah Finch finished.

‘Pretty crazy time’

The pandemic sent everyone home in March 2020. They chatted over the internet instead of each other’s shoulders.

Choi found more time to work on the project as many of his students dropped off from their classes in the upheaval of the pandemic, and while working from home, he spent more time with his sons, Sam, 5, and John, 3.

The team taught Emora about COVID and programmed sentiments of sympathy and encouragement, but they made Emora and her virtual world unaffected by the virus so as not to further depress everyone.

They were working 60 hours a week or more to get ready for the Amazon competition.

The global Alexa Prize SocialBot Grand Challenge is named for Amazon’s virtual assistant, Alexa. The awards, typically held in person, were virtual.

“So it’s a pretty crazy time right now with the coronavirus going on,” Emora said to a judge during a demonstration. “Are you and your family doing OK?”

“We’re doing good,” said the woman.

“That’s good. Do you feel like it’s harder to stay connected with people these days?”

“It has not been a problem.”

“That’s good to hear,” said Emora, adding, “It is always good to remember that this isn’t permanent and it will calm down in time, so just keep doing your best.”

The judge smiled and nodded.

Team Emora won 1st place, Amazon announced Aug. 4, 2020.

With $500,000 and recognition from leaders in the field, the team decided to start over.

Learning

Choi is a reviser.

In the extra time he spent at home, he grew fascinated watching his son Sam learn. “The children are amazing creatures,” Choi said.

Choi had first imagined the chatbot as intelligent and wise. Watching Sam, Choi decided he wanted Emora to learn as easily as a child, to be as curious and inquisitive.

“I will be very happy if the bot can talk like a 5-year-old child,” said Choi. With current technology, chatbots don’t evolve even as they have thousands of conversations, as the bots in the Alexa Prize contest do. “If my kid talked to 5,000 people, I can’t even imagine.”

For this year’s Alexa Prize competition, the team reworked the programming to teach Emora to learn. They gave up a lot of control over what Emora says. It grew harder to write a script because Emora would push back, the Finches said.

Emora was helping build herself. “That’s exactly what children do,” Choi said.

The team didn’t finish the redesign in time for the 2021 Alexa competition. It may take a few more years before Emora can help people with depression, anxiety and isolation on a large scale. But Emora still got strong ratings in the Alexa competition.

The team’s short-term goal is to have Emora integrated into Emory so students can use the app to deal with day-to-day issues and navigate life on campus. After an upcoming trial, Emora could be available for all students in 2022, Choi said.

Meantime, the team keeps thinking of ways Emora could help. They think of parents who struggle to keep up with their kids with virtual learning or people with memory issues.

Lately, Choi’s been thinking of this: “After I die, if I had made myself as an avatar on the bot, my son could actually still talk to me.”

He doesn’t want Sam and John to think the bot is him, more like someone who has access to his brain. He imagines a son asking Emora for advice from his father in a hard situation.

Emora, Choi imagines, could tell the boy, “Your dad would have said, ‘Do this.’”