Debate grows over Sonny Perdue as possible Georgia system chancellor

For many, the idea of former two-term Gov. Sonny Perdue becoming the chancellor of the University System of Georgia comes down to one question.

Should someone without higher educational administrative experience lead a system of 26 colleges and universities?

The state’s 19-member Board of Regents are hearing arguments on both sides as they prepare to interview Perdue for the job, possibly on Friday, several people with knowledge of the search process told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Regents guidelines require them not to discuss personnel matters, and members have been tight-lipped about the search process. No information about the search has been posted on the board’s chancellor search page since April.

Several colleges and universities have hired former elected officials to lead their schools. University of Kentucky professor John Thelin, who studies higher education and public policy, said schools hope the person’s name recognition will draw more donors.

In Georgia, the results have been mixed. Young Harris College, a private school in the North Georgia mountains, named former Georgia Secretary of State Cathy Cox its president in 2007, a position she held for 10 years. She’s now president of Georgia College & State University. In 2016, then-Georgia Attorney General Sam Olens was named Kennesaw State University’s president. He left less than two years later, shortly after a state report found KSU ignored guidelines in its handling of a protest by several cheerleaders.

The AJC first reported in March that some regents wanted Perdue to become chancellor. The search, though, was paused last spring. Gov. Brian Kemp’s inner circle has intensified its behind-the-scenes push in recent weeks for Perdue, who has helped Kemp throughout his political career.

Perdue’s opponents have framed their argument around his inexperience running a college or university.

“Sonny is a career politician with no experience in campuses or classrooms except defunding them,” said Alex Ames, a second-year Georgia Tech student who organized the group Students Against Sonny.

The group’s critique caught the attention of prospective college students like Abeeha Bhatti, 18, a senior at the Gwinnett School of Mathematics, Science and Technology. She’s been accepted to several top University System schools, but is worried Perdue may support policies that cut the state’s college scholarship programs.

“He’s not necessarily one who wants to make education accessible to everyone,” Bhatti said.

Perdue, who was governor from 2003 to 2011, made changes to the lottery-funded HOPE scholarship program, which covers most in-state tuition for students who maintain a “B” average. This included a new system to evaluate whether students met the academic qualifications. Critics say Perdue’s changes made it tougher for students to keep the scholarship.

Joshua Gregory, 20, a third-year University of Georgia student who leads its College Republicans group, has friends on both sides of the debate. He personally believes Perdue’s connections among state and national Republicans could help with fundraising and lobbying efforts.

“I understand the response that he doesn’t have experience in higher education administration and while I do think that would be a good quality to have in a chancellor, I think that Sonny balances it out with his years of executive experience in high-level organizations,” said Gregory.

Former regent Philip Wilheit said of Perdue: “I know Sonny. I like Sonny. I just don’t feel like he’s the best qualified candidate to run what I think is the best university system in the nation.”

Thelin said there will always be “pause” among some if the job candidate has no academic background. Perdue, he said, can be effective if he works well with different groups, particularly Washington, D.C.-based education organizations who can shape opinion about colleges that could impact donations.

Erroll Davis acutely understands the debate. The longtime utility company executive became the University System’s chancellor in 2006 — with Perdue’s support — despite having no administrative experience in higher education. He recalled one challenge was working with state lawmakers, who significantly cut the system’s budget during the Great Recession.

Davis, who was in the job for about five years, learned much of the job is administrative and about relationship building.

Ultimately, Davis said, “This system is going to endure, no matter who is chancellor.”

Staff writer Greg Bluestein contributed to this article.

From politics to academia

Here are examples of some people who have made the switch.

Cathy Cox

Cox was Georgia’s secretary of state from 1999 to 2007 before becoming president of Young Harris College in North Georgia later that year. She worked there for 10 years before taking a job as dean of Mercer University’s law school, her alma mater. Cox was named president of Georgia College & State University in October.

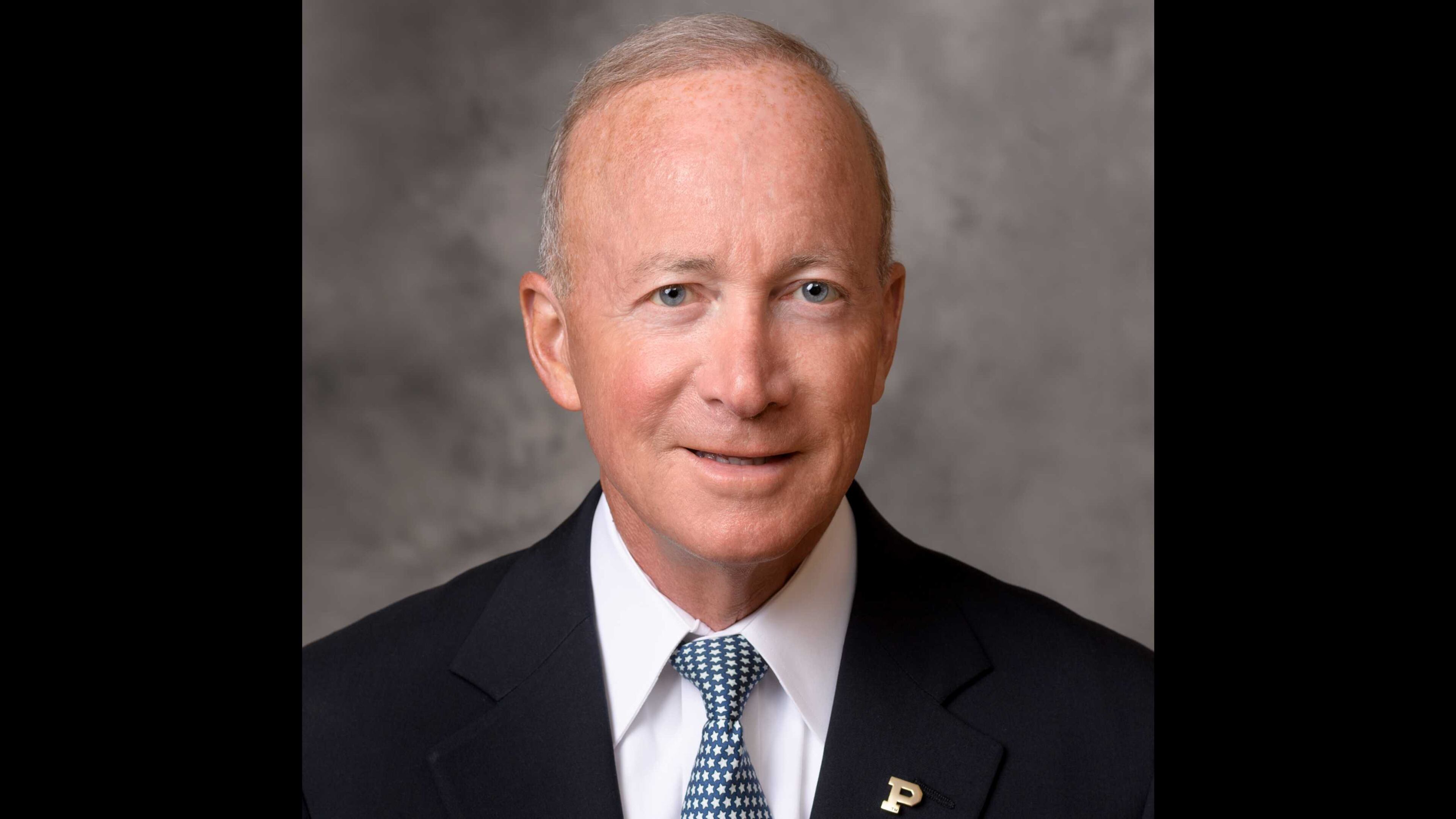

Mitch Daniels

Daniels became Purdue University’s president in 2013 after two terms as Indiana’s governor. He’s still in the position.

Janet Napolitano

The former U.S. Homeland Security secretary had no experience in higher education leadership before becoming president of the University of California in 2013. She initially received low marks for a top-down managerial style, but was praised for opening the system to more students. Napolitano resigned after seven years on the job.

Sam Olens

Olens, former Cobb County commission chairman, was the state’s attorney general when he was picked by the Georgia Board of Regents in November 2016 to be Kennesaw State University’s president. He left the job in February 2018 after a state report found Olens and other administrators ignored guidelines on its response to a protest by some cheerleaders.

Donna Shalala

The former U.S. Health & Human Services secretary was the University of Miami’s president from 2001 to 2015. Shalala was credited with expanding the university’s research capabilities. Critics note her tenure included improper benefits to some student athletes and its medical school laid off several hundred employees after it failed to meet its budget.