Cobb school district faces criticism over response to controversies

Georgia’s second-largest school district faces mounting scrutiny about how it responds to critics, including a student, and most recently about the past writings by some members of its communications team.

Amid recent debates on topics ranging from book bans to public speaker sign-ups — on top of long-standing partisan tension between the district’s elected officials — more attention has focused on how controversies are handled and who helps shape the district’s messaging.

Three administrators in the Cobb County School District had ties to the leader of an anti-LGBTQ+ group, the Cobb County Courier recently reported after reviewing writings published online before the employees served in their current roles.

The online publication’s investigation uncovered a series of essays penned in the last decade on some far-right websites by Julian Coca, the district’s director of content and marketing, about homosexuality and other topics. The websites were connected to American Vision, an organization that supports the death penalty for homosexuals, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Eric Rauch, a digital content specialist for the district, also worked for American Vision as a director of communications, and as a vice president at a related company after that, the Courier reported. John Floresta, the district’s chief strategy and accountability officer, penned essays about education for connected sites, including one titled “Does Public Education Stink?” from 2013.

In one article attributed to Coca, he wrote that homosexuality is “culturally destructive.”

The district did not dispute any of the Courier’s assertions. Instead it questioned the credibility of reporter Rebecca Gaunt and the outlet, hinting at past issues with accuracy and “doxxing” of employees. Doxxing is the practice of sharing someone’s personal information — such as addresses, phone numbers — online to incite harassment.

“It is a sad day when schools must take time away from students and teachers to comment on a freelance writer’s attempt to dox veteran teachers, stalk their families on social media and pull their children into the news,” the district wrote in a statement.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution requested an interview with Superintendent Chris Ragsdale, but did not get a response. Floresta reiterated the district’s formal statement when reached by the AJC. The Cobb County School District routinely refuses to respond to requests from Gaunt, she shares on X, formerly known as Twitter.

It’s the latest news in a series of events that paints Cobb as an increasingly politicized district, where critics say undercutting dissenting opinions — including in internal emails — seems to be the go-to move.

The Cobb school district had the same response two weeks ago when a group called the Cobb Community Care Coalition held a press conference to publicize internal messages, including one to the AJC. The emails and Microsoft Teams messages between members of the district’s communications staff, including Coca and Floresta, appeared to discuss ways to minimize dissent at public meetings. The group obtained the information via an open records request.

The district accused the group of “doxxing veteran educators” and questioned its credentials, in a statement given to the Marietta Daily Journal.

Some of the messages made public were about a student, Lily Mosbacher, who was interested in speaking at public comment. A junior at Pope High, she wrote an op-ed for the AJC in September criticizing the district’s recent moves to restrict reading materials for students. District officials heard that she was thinking about addressing the board in September, and records show they gave each other a heads-up. Her mother, Jennifer Mosbacher, serves on the Cobb County Board of Elections, which is involved in a lawsuit over the district’s redrawn school board maps, “so she probably doesn’t want to be in the limelight on this particular issue,” one message read.

“It was weird. It’s kind of creepy. It kind of freaks me out, how my administrators were probably talking about me behind my back,” said Lily Mosbacher, who thought the adults at her school and district would have been impressed that she took the initiative to get her ideas published. “I think they care because it’s giving them a bad rap in the press ... It’s kind of ironic.”

Lily Mosbacher never signed up to speak at the meeting.

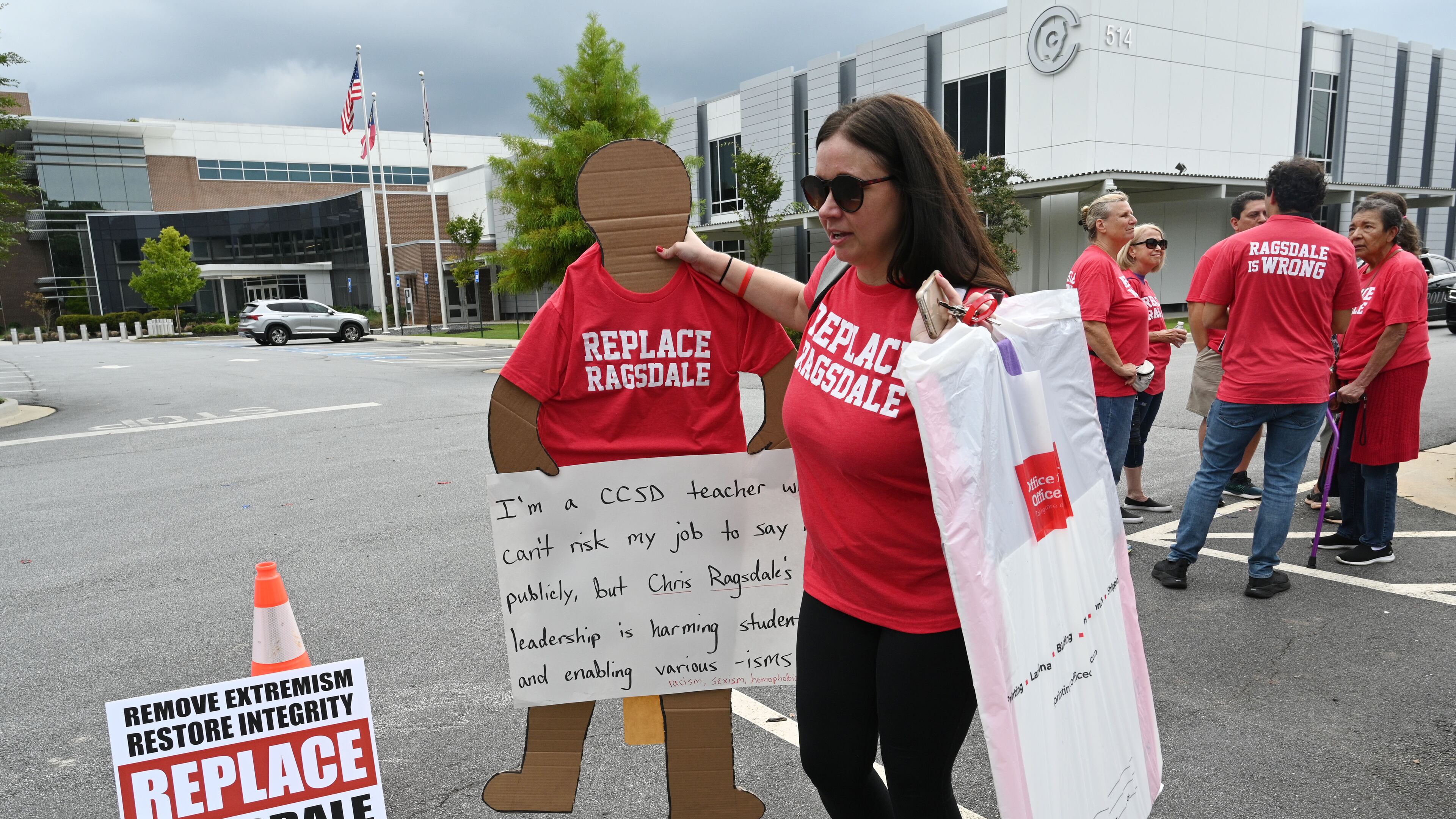

The messages were made public after a particularly contentious school board meeting in September, when district staff unexpectedly moved the sign-up location for public comment, resulting in shoving and yelling as people attempted to register for limited spots to speak. Some had taken part in a “Replace Ragsdale” rally earlier in the day or wanted to talk about the district’s recent decision to remove some books from libraries.

Whether the district was truly attempting to restrict viewpoints in September comes down to intent, said Joy Ramsingh, an attorney and board member at the Georgia First Amendment Foundation.

“But even if that intent would not be provable in a court of law, it certainly is not going to improve their standing in a court of public opinion,” she said.

That public opinion was tested in October, when the district sent a message to all families from its attorneys that decried “leftist activists” after the county’s Board of Elections settled a legal battle over the school board maps. The message sparked outrage from some local Democrats.

Typically, organizations want to get negative stories out of the news cycle as quickly as possible, some public relations experts said in interviews.

“On one hand, if they really were doxxed in how I would typically think of the word, I would be like, ‘Oh that’s a very supportive response.’ Like, ‘Good job protecting your employees. That isn’t something we should encourage.’ But if it wasn’t to that extent, then it does seem oddly hostile,” said Myiah Hutchens about the district’s response to questions about its employees’ histories. She’s the chair of the Department of Public Relations at the University of Florida whose research focuses on how communication functions in democratic processes. “They’re elevating the situation rather than just trying to put it to bed.”

Reputation is one of an organization’s most valuable currencies, said Barbara Gainey, the director of the School of Communication at Kennesaw State University who studies public relations in school systems.

“It takes a lot of time to build that level of public trust and that good relationship with your constituencies,” she said. “It’s hard to be as successful and as effective if that trust is not there.”