A year into University System of Georgia’s renaming push, little to see

Henry W. Grady III has heard and read many things about his great-great-grandfather in recent years.

Some celebrate Grady, editor of The Atlanta Constitution, as a cheerleader for the reconstruction of Atlanta and the “New South” after the Civil War. Others, after reading some of his speeches and editorials, say Grady was a white supremacist.

At the University of Georgia, where Grady’s name stands on its journalism school, and at other Georgia universities, there are passionate discussions about the appropriateness of buildings named after people with direct and indirect ties to slavery, segregation or white supremacy. Grady’s critics note he once wrote “the white race is the superior race.”

The University System of Georgia, the state’s public system, created an advisory group a year ago to review building names of its 26 colleges and universities. It held its first meeting on July 9, 2020, another in September, but no public meetings since. There’s no public timetable on when the work will be completed. Some students and activists are frustrated by the group’s pace, and that no names have been changed.

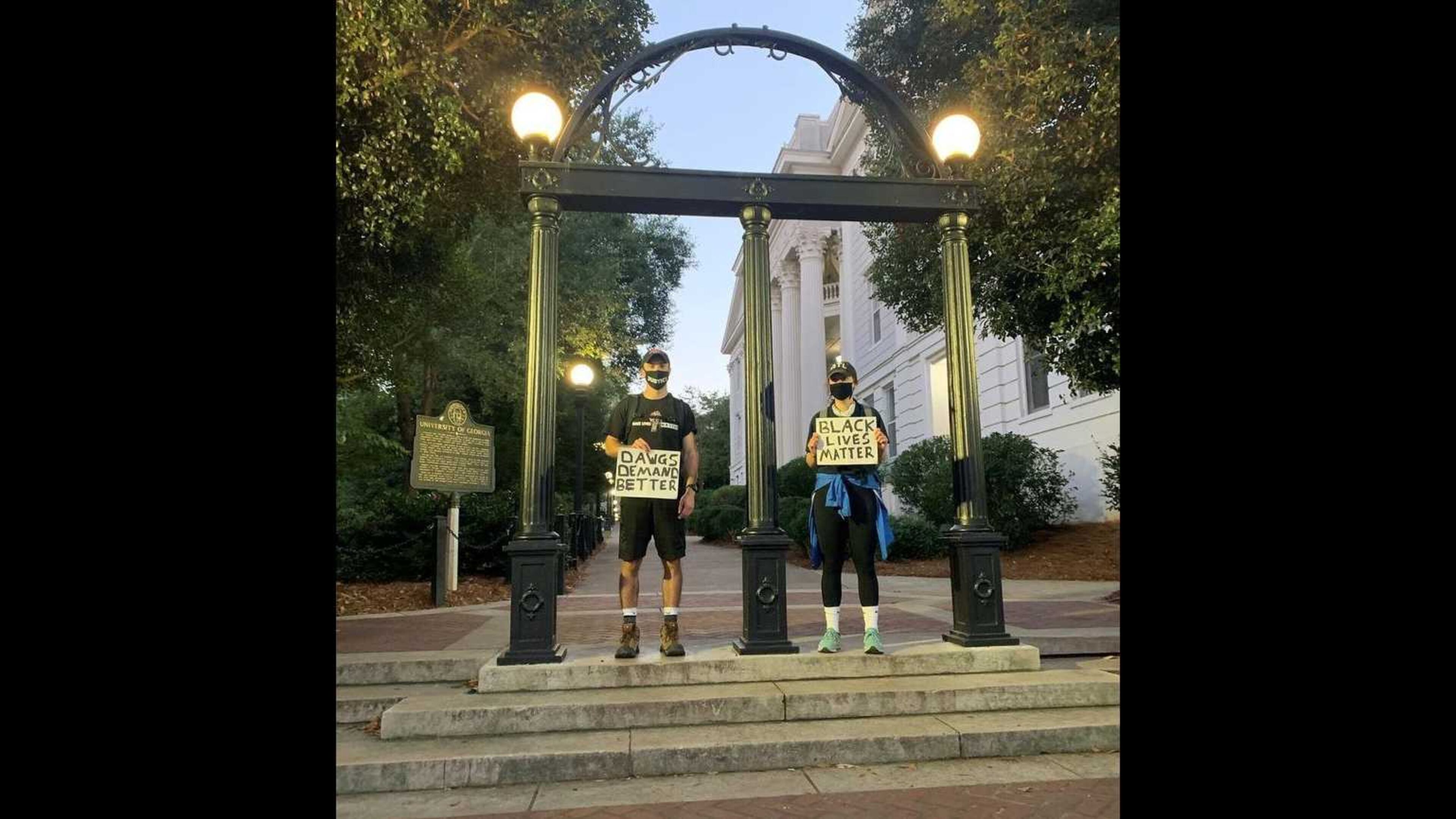

“If I had to put complicated feelings to it, I am disappointed, but unsurprised,” said Jay Mathias, a white University of Georgia graduate who helped start Dawgs Demand Better in June 2020 to address racial disparities at the school. “That said, I remain hopeful and optimistic that through USG’s work and continued advocacy, change is within reach.”

The University System, which is searching for a new chancellor, said last week no one was available for an interview. A spokesman referred The Atlanta Journal-Constitution to information on its website about the advisory group, which posted a statement in March saying it is working with historians on ongoing research and will present any recommendations to the state’s Board of Regents, which oversees the University System’s operations.

“While the group anticipates completion of the project soon, it has been focused on thoroughly reviewing the information it has been provided and therefore may take a little longer,” the statement read.

Henry W. Grady III, 58, a board member of UGA’s journalism school, said he often feels left out of these discussions, as he sat on the porch of his northwest Atlanta home last Tuesday. More than anything, he wants people to fully study his ancestor’s writings to get a complete picture of Henry Grady before making their judgments.

“These things were not named for him because he gave millions of dollars of his own money to build these institutions. They were named in his honor by people I would think were rational people for their time,” he said.

Changes come too slowly for some

Last year, several colleges and universities began taking stock of their racial history and present diversity in the initial weeks after George Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis police officer, Breonna Taylor was fatally wounded in her home by police in Louisville, Kentucky, and an Atlanta police officer was charged in the death of Rayshard Brooks, and many Americans protested in the streets against police misconduct and racial injustice.

Many schools created committees to review their diversity and inclusion practices, work on ways to enroll more students of color and help them complete their degrees, and explore whether any campus buildings or streets were named after people with racially offensive pasts. In some instances, the demands for change came from white students who are “grappling with a lot of the privilege they grew up with,” said University of Texas history professor Leonard Moore.

Changes on the renaming front in academia, often criticized for its glacial pace in decision-making, have been slow in Georgia and other states. The University of South Carolina’s NAACP chapter held a demonstration in February, saying the school was “dragging its feet” on demands to change some building names. More than 7,000 people have signed an online petition demanding the University of Florida make similar changes.

A few Southern universities have taken action. The University of Alabama voted in September to rename Morgan Hall, originally named for a former Confederate general and Ku Klux Klan Grand Dragon. The University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill is seeking input on renaming three campus buildings.

Moore served on a University of Texas committee a few years ago when its then-president, Gregory Fenves, removed statues of four Confederate leaders from the school’s Main Mall. Fenves last year became Emory University’s president. Emory, the state’s largest private university, announced two weeks ago it would rename a hall that was named after two former presidents who were slaveholders and consider other changes to address its foundation on land owned by indigenous people taken by the federal government. In making the name change, Fenves considered recommendations from a university committee and sought approval from the Board of Trustees.

Moore, who is Black, said he doesn’t believe in removing all statues or renaming buildings. He suggests providing context, perhaps with a plaque, to explain why what’s there is there.

“I really believe as an academic institution, I just don’t think we should be taking names down or things of that nature,” he said. “I think we miss out on very valuable conversations when we do that.”

The debate at UGA

Much of the debate concerning renaming buildings is centered at the University of Georgia, the “birthplace of public higher education in America.”

Several of its initial leaders were slaveholders, records show. University historians and faculty have created websites with research on the topic. UGA’s founder and first president, Abraham Baldwin, said slavery should be a matter left to the individual states, not the federal government, faculty note. A hall is named after Baldwin: It had been constructed in 1938 on top of a slave burial site, a discovery made in 2015.

Dawgs Demand Better has identified 22 campus buildings where it would like to see name changes. Its online petition seeking various forms of racial justice at the university has more than 2,500 signatures. Prominent Black UGA alumni such as pro football Hall of Fame member Champ Bailey signed the petition, Mathias said.

UGA history professor Claudio Saunt, author of the 2020 book “Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road to Indian Territory,” believes it’s important for the “community to come together and kind of hash it out and figure out what they want to prioritize and who they want to commemorate.”

Saunt is particularly curious about places named after Wilson Lumpkin, a former governor, U.S. senator, UGA trustee and commissioner to the indigenous Cherokees.

“Lumpkin, in his words, said it was his life’s mission to ‘expel the Cherokees from Georgia,’ " Saunt said.

An Athens street and campus building bear the Lumpkin name.

The Grady name

The University System’s advisory group reported receiving more than 1,500 submissions in an Aug. 13 update. Mathias believes he’s submitted about a dozen comments. He wants more transparency about the process. The name changes, he said, should include UGA’s Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication; he described Grady as a “white supremacist.”

Some have suggested a name change to Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, the public medical facility he pushed for that opened in 1892, three years after Grady died.

Atlanta school board members voted in December to rename Grady High School as Midtown High School, effective this fall semester. Henry W. Grady III said he had no real input in the discussions. In some ways, he’s become a spokesman for the family name.

The lack of outreach by critics frustrates him. The family mausoleum, he said, has been desecrated twice since April 2020 with profane words calling the Gradys “racists.”

“I don’t understand the venom,” he said.

Grady III learned about his great-great-grandfather from his father, who proudly told him stories about Henry Grady. Grady III said Henry Grady occasionally said different things to different audiences, but the goal was to help Atlanta and the entire South.

“He wanted the South to be rebuilt and rise again. And it was lift the tide of all boats, not one over the other,” Grady III said.

Grady III said he’s OK with changes, such as hyphenated names to any buildings, as long as it’s done with thorough deliberation.

“If you change it, change it for the better. But do it consciously, not reactively,” he said.

Saunt said many of the people who named these buildings decades or even a century ago were committed to slavery and segregation. They also had an inaccurate history of these individuals based on little input and research from people of color, he said.

Moore added the problem is many buildings are named after people who’ve made financial contributions to a school. Georgia State University announced plans in 2017 to name its football field after entrepreneur Parker “Pete” Petit, who donated more than $15 million to the school. Petit was charged by federal prosecutors with fraud in November 2019. The university last year reached a 15-year, $21.5 million stadium naming-rights deal with Center Parc Credit Union.

“If I ever become a college president, this is going to be Building A, Building B and Building C,” he said.