In the eye of the housing storm: An interview with Atlanta developer Egbert Perry

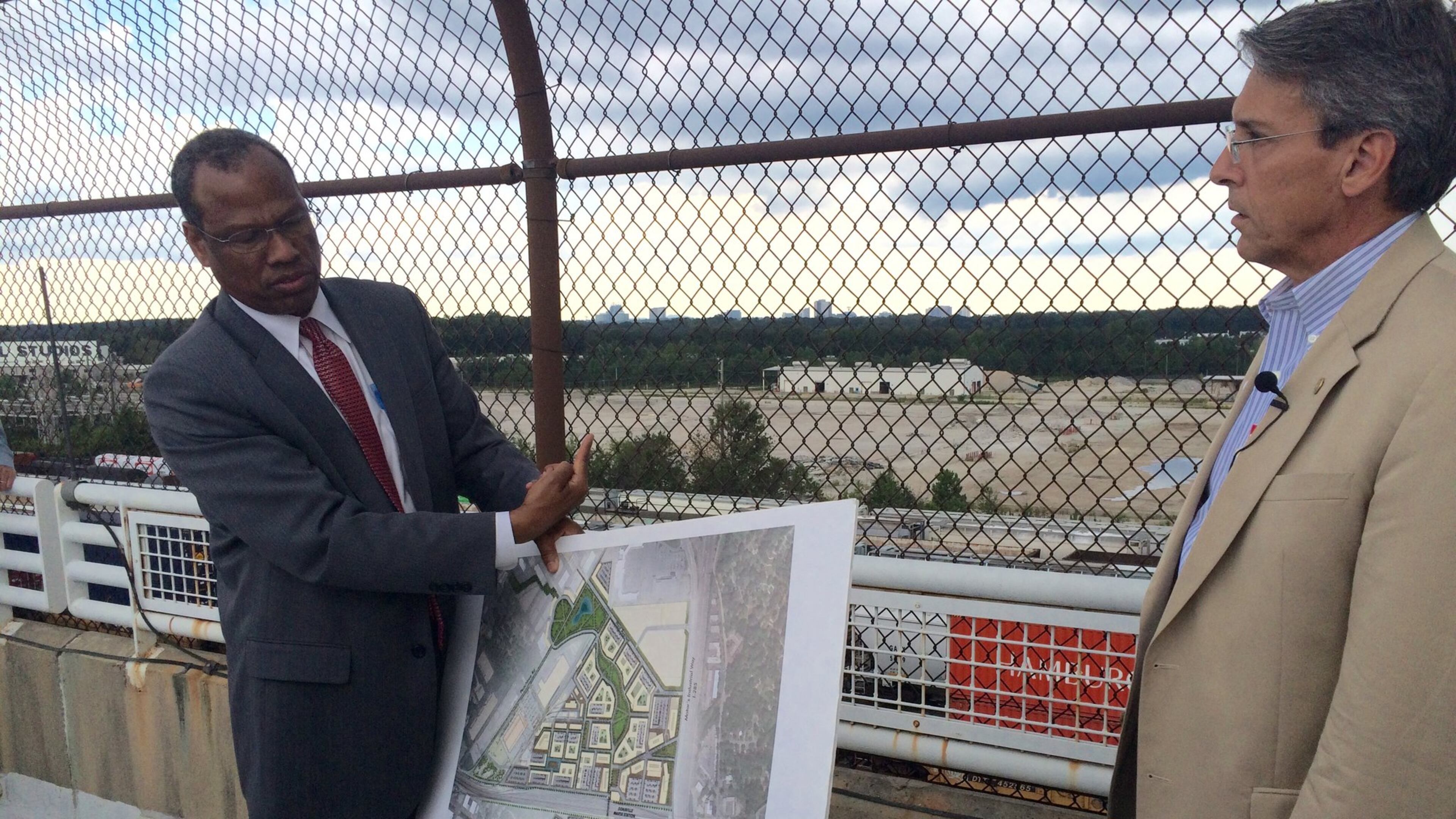

Egbert Perry, one of Atlanta’s better-known chief executives, runs the development firm Integral Group that is redeveloping the old GM plant site in Doraville. For the past 10 years, he had a bird’s eye view of the broader economy as a board member and later as chairman of home mortgage giant Fannie Mae.

In December, Perry stepped down as chairman of Fannie and sat down with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution to discuss his time on the board of the government sponsored entity. Fannie, which along with Freddie Mac, guarantees mortgages and helps ensure that the housing market can function.

The two “GSEs” went through conservatorship following the financial crisis. Perry and fellow board members who joined the Fannie board in 2008 had to help right the ship. He said Fannie and Freddie were vilified unfairly for their roles in the housing crisis, and since the financial collapse have been vital cogs in revitalizing the housing industry.

Perry was born in Antigua and immigrated to the U.S., attending the University of Pennsylvania and obtaining an MBA from the Wharton School of Business.

He also discussed his views on the overall economy and on Atlanta. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q: When you stepped onto the Fannie board in 2008, what was going through your mind watching the stock market crash and job losses rising?

A: You definitely had a sense that you were in the middle of something very scary. …I wish I could say we went in there and we did X, Y and Z because we just were so great. The truth is the first year we were trying to understand how the place worked, what was wrong, how we got there. I sort of put the life of Fannie Mae into three stages: The first stage was freefall. 'OK, what the hell is going on and what do we need to do to stop this from crashing? Let's turn over every rock and find out what's wrong and what we need to do to stop it or fix it.' That was Stage One and that probably lasted two-and-a-half or three years.

Then it was, ‘OK, we understand what’s wrong and we handled a lot of the low-lying fruit,’ but then you went into that next stage which was, ‘OK, let’s start to repair some of the fundamental infrastructure in the place and put in place some control systems … that focus on making sure this can’t happen like this again.’

Q: More than 10 years since the start of the Great Recession, there have been many reforms, but is there a risk of us forgetting the lessons of the Great Recession?

A: There's always the risk that memories get short, but the bigger risk – there's two risks – greed kicks in, and you start ignoring some of the things and you think you'll be in and out before the crash. That's one thing. And remember, there will be a new minted group of MBAs in 10 years that for whom this period was just something they read about in a book, and didn't live through it, so they won't relate to it as first-hand knowledge and hard-earned experience. They'll think, 'I'm smarter than the next guy. Here's what we can do.' Same time they're coming out some of their colleagues are going to work for banks, investment banks and commercial banks, so the question is, 'Do we have durable regulatory controls that will put a limit on how far outside the box you can go in a regulated enterprise?'

Q: What’s your view on where the housing market is today?

A: I will start by qualifying that there are a lot smarter people who are economists who study the data all the time who are probably more qualified to answer that question. …I would say there are a number of problems that are headwinds. The lack of supply of housing, because we are at a fraction of what we used to be in production.

We’re not building a lot. And there are a number of reasons. …Our (construction) workforce, a lot of the production capacity that was in place before the crash was never put back into place. Lumber mills and drywall plants and concrete — a lot of the production was never built back to the levels it was before and for good reason. So all of that means there’s a scarcity of finished product — houses — and the scarcity is driving prices up. At the same time, wages don’t grow like that.

You have two things competing that are making housing costs more and more unaffordable. What you can do to change the overall cost of money (lowering borrowing costs), is somewhat small in relation to the other issues. The largest exposure is, what can you do to lower the cost of the house itself?

You need a lot more state of the art ways of building housing. We still build houses the way we built houses 100 years ago.

Q: Does that mean more advanced manufacturing?

A: Modular construction, yes.

Q: Is it changing zoning?

A: Absolutely. The fact is we are very inefficient in the use of our land. It's great that everybody aspires to have a big yard …and this mansion but the truth is the urban centers are now becoming more efficient in the use of land and you're seeing smaller townhouse units being a more common product. That's a result on the continued pressure to optimize the use of land and it makes sense. The reality is we really don't need these big houses.

The challenge isn’t trying to get everyone living in small units in urban centers and densely populated areas, it’s a matter of having a resilient city and that’s one that offers choice. Some people want to live way out and they want to be on a big spread with either a big or small house and that’s where they want to be. That option should exist, but it’s just that you are finding a lot more people want to be connected. They want to be connected to roads, transit and internet. There’s a different way of living and as time is passing it’s moving to those preferences in a greater proportion.

Q. Did metro Atlanta miss an opportunity coming out of the downturn to try to tackle some of its affordable housing challenges?

A: Most cities did and Atlanta did as well. …There's a saying, 'You don't learn in times of success you learn in times of failure.' When we were doing well we weren't building for the bad times. We weren't investing in those things. The thing that makes more livable places, communities where you have – everybody thinks we have an affordable housing crisis. I've said repeatedly. everywhere, every chance I get, we know it's not just an affordable housing crisis. I could take 500 acres of land in a place nobody wants to be and build nice low-cost housing and I bet there won't be a long line of people waiting to go there. It's not a housing issue, it's a matter of housing affordability in place where people live or would choose to live. And that's more community development issue than a housing issue.

You have to be able to have what you want as a family. You want to be near decent schools, you want services, you want parks, you want quality of life infrastructure. If you’re not addressing quality of life infrastructure at the same time you are locating housing you are not solving the problem.

Q: The Serta Simmons Bedding headquarters is well underway at your Doraville project at the old General Motors plant. What’s next there?

A: We have a few announcements we hope to be making in the late first quarter or second quarter. We're largely working in a portion of the site known as the Yards, over by Chamblee and Peachtree Road because when we started there was a lot of demand for that authentic feel in that part of the site.We have some uses and users that we are going to announce and other developers doing other projects on the site.

Q: Is this still in your mind a 10-year project?

A: Yes. And if you forecast in there somewhere two or three-year period of slower growth because we hit a recession that just adds to it. But I think because of our transit connectivity and road connectivity and the airport there are reasons we think we are less vulnerable than other sites.