The bald and the beautiful: Black women need to get real about hair weaves

BY DEBRA SHIGLEY/ FOR THE AJC

August is National Hair Loss Awareness month. For the past ten years, experts in the field have used the time to focus on ways to prevent and treat hair loss. The following essay is by Debra Shigley, founder of the Colour app -- a hair styling service for women of color. Shigley, an author and former attorney before venturing into the beauty business, says we are long overdue for a candid conversation about the hair loss epidemic among women of color and one of its main causes -- hair weaves. Visit Debra at www.getcolour.io or email her at debra@getcolour.io.

At any given time, 50 percent of black women are hiding their real hair with fake hair.

Despite the natural hair movement of the past decade which has led black women to abandon chemical straighteners, for some women, dealing with curly and tightly coiled hair feels like a daily chore.

One of the options for managing our hair is to sew another woman’s hair into our own. This process is clinically proven to cause permanent hair loss, yet as a community, we have spent decades minimizing the effects of this particular hair practice to seem inclusive and not self-pathologize what we’re doing to meet white beauty standards. But if white women were permanently losing their hair, somebody would be screaming from the rooftops.

This isn't a question of who is selling out more—the naturals, straight-naturals, the relaxed, or the weave-wearers. It's a question of baldness, and it needs to be addressed.

Like many successful consumer products, hair weave is addictive. My friend Alice* remembers her first hit. She saw her from across the room, and it was love at first sight. It was long, blonde and Barbie-like, swishing with every step as her colleague strode through the hallway.

“That was the first time I had met someone in my every day world that had a weave,” recalls Alice. “Before, weave seemed inaccessible to me—something only models, entertainers or strippers did.”

A few weeks later, she found herself at a celebrity stylist’s shop plunking down $1,500 for her new locks. That’s $700 for the hair, and $800 to have it put on her head. When she saw the long hair flowing down her shoulders, Alice felt it was worth every penny. “I got more attention from men of all races. I felt like I’d been upgraded,” she said. “My market value had gone up."

Alice is a good friend and full disclosure, I recently asked her about her love of weave as part of a customer discovery exercise for my business, a hair care app called Colour. If you think it’s self-serving of me, as the founder of a hair styling business to write about this topic, maybe you’re right.

I’ve never worn a weave, myself, and am not theoretically against it. Every woman partakes in activities to look and feel beautiful, from plumping her lashes to shaving her armpits to painting her toenails.

It wasn’t until I started seeing the damaging effects of weave among our clients and community —contrasted to the total unwillingness of most thought leaders in black hair to speak out about the paradox (that a great solution to manage our hair is to hide our hair) or acknowledge the health implications of the practice—that I needed to dig deeper and better understand.

A SKEWED STANDARD OF BEAUTY

The debate over whether Colour should install sew-in weaves (we currently don’t) has caused me to question the entire purpose and mission of our company.

When we were undergrads at Harvard 17 years ago, my friend, Shanya Dingle, was one of my interview subjects for a story about beauty standards that caused a firestorm on campus.

My roommate and best friend, Jennifer Hyman (founder of Rent the Runway) and I, over the span of four days, interviewed dozens of women on campus from different ethnic backgrounds about their feelings on being left out of the ideal Harvard beauty.

The Harvard beauty ideal, students said, was that of an ultra-petite, long blonde haired, sweater-set girl. As a biracial woman who is half Jamaican, half Jewish, the sentiments Black women shared haunted me.

Shanya argued that we can’t forget that beauty is socially constructed; that the beauty “ideal” is a function of the power structure.

“I wonder what it would be like if blackness were the standard . . . while white women sat in the hair and tanning salons trying to look like me. Can you really imagine white women en masse, going to a salon to try and have afros?” she asked. I couldn’t really, at the time.

My experience writing the story stayed with me over the next decade. I felt a personal mission and over time, saw an economic opportunity to solve the specific problem of black hair.

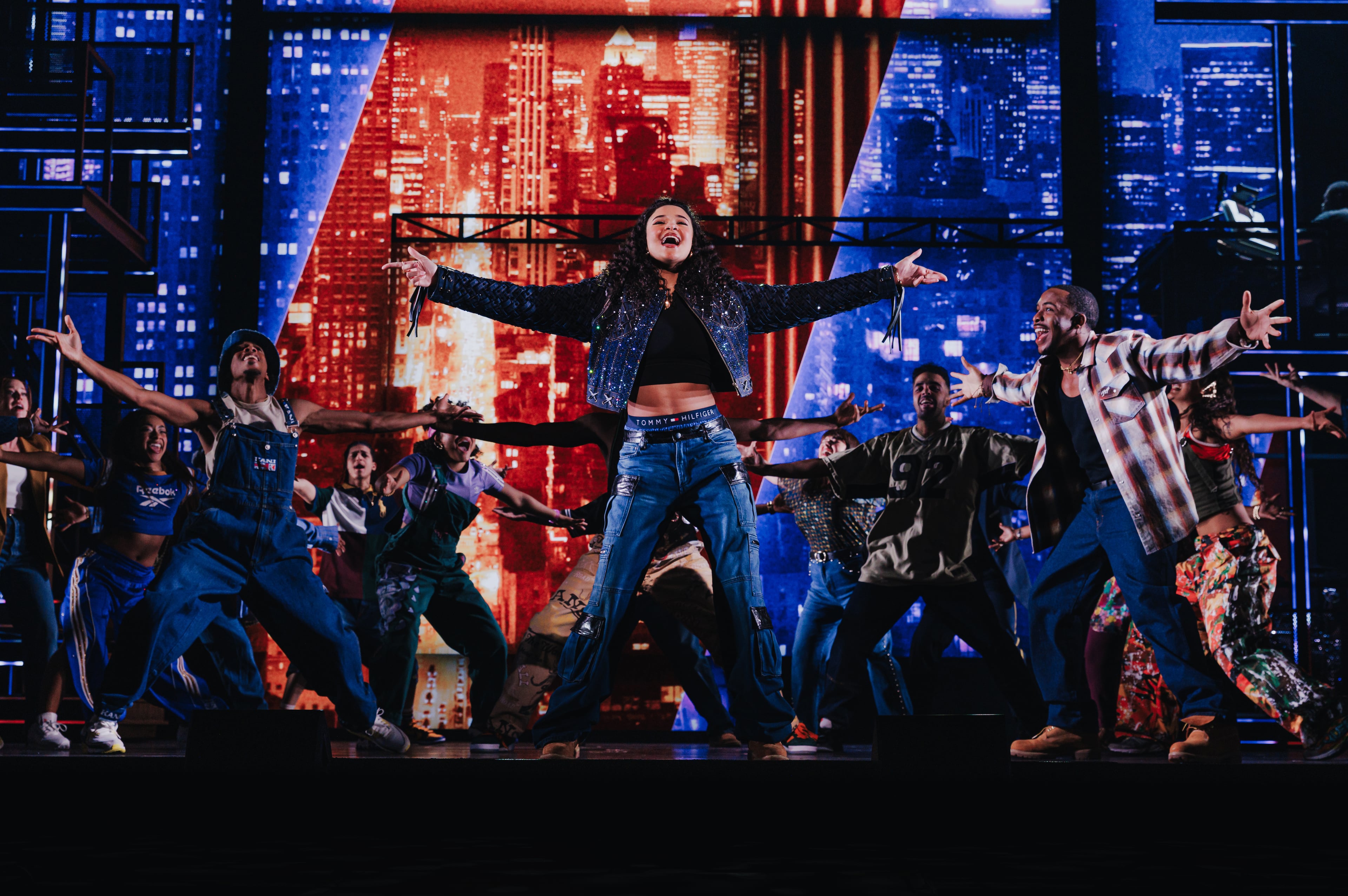

VIDEO: The state of the Black Hair business with Debra Shigley and Lois Hines

As I moved through a career trajectory as a journalist, author, television commentator and lawyer, my personal hair story got more complicated. It was really inconvenient with a corporate job to deal with my ultra curly, chemically straightened hair.

When I was a lawyer in Washington D.C., I remember spending all day Saturday at a Dominican salon (the original blow dry bars), sweating under a hooded dryer, and thinking there has to be a better way. Later, I would leave during my lunch break to sneak in a hair wash at a salon near my office, only to return five hours later.

For the unacquainted, styling black hair itself can be an hours-long process, and ethnic salons are notoriously inefficient operations. It's common for stylists to double book, run behind, or never even show up for appointments. This phenomenon of poor customer service even inspired a hashtag #blacksalonproblems that garnered 150,000 tweets in just hours when it trended last year.

After I stopped chemically relaxing my hair and let my natural coils grow out completely, I felt that in spite of the countless blow dry salons that had popped up nationwide, there needed to be an option for women who wanted to embrace their hair texture.

We had entered a space where Afros were literally sprouting up everywhere, from celebrities like Solange, to Youtube hair influencers, to the Curlfest conference in New York. It seemed like everyone I knew was going natural, dawning a potentially new era in hair freedom and acceptance.

BLACK HAIR ROOTS RUN DEEP

Obsessed with a vision to shake things up and offer my dream hair styling experience, I went to beauty school when I lived in Mexico City, found a great co-founder, and built an app, which launched last year.

At first, I felt the urge to keep our marketing light —maybe Colour is a service where we just do hair, all bubbles and roses, and no political implications— but lately I feel that we can’t ignore the elephant in the room. We can’t just talk about making hair styling convenient without addressing why black women choose certain hair care practices and styles to begin with.

In the endless discussions of good hair vs. bad hair maybe we haven’t adequately addressed, as feminist scholar bell hooks recently posited, how we are all complicit in white supremacy in beauty.

At a recent panel discussion posted on the website For Harriet, hooks said she's argued "somewhat unsuccessfully," that we are implicated in our positioning Beyoncé as the most beautiful black woman.

“Sometimes I see her and I’m just awed by her beauty,” hooks said. “But then I’m thinking, if this is the most beautiful black woman and she has this false, straight blonde hair and this super light skin, I think, how far have we gone? How can [young girls supporting her] feel that their natural hair is in any way beautiful?"

The flipside of the argument is that it’s about survival. For African-Americans, historically your hair texture reflected and determined your life status: are you a slave working in the field (bad hair ) or privileged to live in the Big House or even “pass” for white (good hair). That’s where the tension lies.

One could argue, if a Eurocentric beauty ideal still exists, anyone who wants to come up can and should get long hair and see how that changes her position. But shaming black women for using tools like weave sends an equally painful message suggesting black women stay in their place and not aspire to the ideal.

TO WEAVE OR NOT TO WEAVE?

To put some numbers to the appetite for weave in the black community, Mintel reported in 2015 that 44 percent of black women have worn a weave or wigs in the past six months. The stat is probably much higher in Atlanta, aka the weave capital of America.

Paula Lundy is a master cosmetologist in Atlanta, who started her career as a schoolteacher before transitioning to her first love, hairdressing. She’s built a following on Instagram of more than 60,000 fans, partially through great photos of her sassy short styles, and her passion against extensions, using the provocative hashtags #wearyourhair and #idareyou.

She's part of a growing chorus of stylists speaking out against what they see as an epidemic of sew-ins, including Atlanta-based Jasmine Collins aka Razor Chic , who has more than 500,000 followers on Instagram and rose to fame posting shocking "before" videos of her balding clients without their weaves.

“Black women have become so dependent on [weave],” says Lundy. “They’re bald all the way back to ears and continue to get weave. Their edges are being ripped out. You feel like you’re not pretty or attractive if you don’t have Asian or Malaysian [hair] sewn-in.”

One justification women use for weave is that it is convenient, especially when it comes to working out. You don’t worry about sweating out your hair when you have a weave, for example. Lundy is unconvinced.

“With weave, you’re not able to shampoo your hair. You can’t touch your scalp. You have a net. The braids [underneath] are full of dirt and dandruff,” she says. The convenience rationale is all b.s. she says. “It’s a smokescreen for ‘I don’t feel cute without this weave.’ There’s nothing ‘protective’ about these so-called protective styles!”

TAKING A WEAVE-CATION

Earlier this year, we launched a small “Weavecation” campaign, as part of a playful way to speak to the issue of taking a weave break. One of the health issues is that women are wearing back-to-back weaves nowadays, instead of taking a break between installs.

Dr. Yolanda Lenzy, a board certified dermatologist and leading expert on weave-related alopecia, recommends following at least a one-to-one rule: two months with weave, two months without.

One Colour client, Ebony Hillsman, volunteered for a weavecation and shared her story of losing a permanent patch of hair on the crown of her head. Her experience with weave started innocently enough.

“My stylist started me off almost like a drug dealer will give you a little taste,” she jokes. “I had been very conservative with my hair, and one day she suggested we can try this little quick weave. Before I knew it, I was all the way across town buying the 20 inches!”

One day a particular hairstyle was ready to be removed, but her stylist couldn’t squeeze her in to take it out, so Ebony tried to remove the glued-on hair herself. “Suddenly, I couldn’t see any hair on the top of my head. A patch of hair came away,” she remembers. The loss is basically permanent. She’s seeing a dermatologist, who prescribed an oral and topical medication, but it’s $60 for two ounces of medication. Ebony is not sure the “soft fuzz” growing in is worth the financial cost.

Lundy has seen dozens of women over the past year looking to escape weave, but they come into her salon with unrealistic expectations. They will show her pictures of a post-weave hairstyle they want, but all the models have full heads of hair, whereas these clients often have significant hair loss around the hairline and throughout the scalp.

Model Naomi Campbell has been the poster child for the cycle many black women experience with hair weaves. Images surfaced of Campbell in 2008 and 2012 with major hair loss from decades of wearing hair extensions, yet after more than 25 years in the spotlight, she has never been seen without them.

Lundy remembers one client, who wanted to try a different look and went short after taking out her weave. “She looked in the mirror, and was devastated. She didn’t want to see herself without that hair. I used to feel very sorry for clients but it’s like a drug addict: You keep doing something that’s bad for you. It’s a real addiction,” Lundy said.

Lundy specializes in short hair techniques, and the majority of her clients use chemical relaxer, which is also somewhat taboo in the current natural hair moment.

Though the research is mixed on relaxer’s role in hair loss, she and other pro-relaxer / anti-weave stylists are quick to emphasize that anecdotally, most black women who have used relaxer for 20 years or more still have full heads of hair. With weave, Lundy feels she’s seen too much permanent damage to participate in the practice. “I might make more money if I installed weave, but I can’t bring myself to do it.”

Another friend of mine, Alliah* runs a family weave and wig business and says the business is taking an emotional toll. Alliah hasn’t worn a sew-in herself for six years due to experiencing a bald patch. She feels the product isn’t bad and has had to talk to her staff about not judging the women who patronize the business.

“It’s no different from selling cigarettes or a weed dispensary. A lot of women who come to us have made a series of bad decisions that made them lose their hair,” she said.

There have been times over the years when she has refused to sell to a client, like the time a mother was looking for pageant-ready sew-in hair for a seven-year-old. When we chatted about the ups and downs of the hair business late one night, Alliah sighed, “For years I’ve wanted to write an open letter to black women encouraging our community to love ourselves as we are.”

HOW THE HAIR WEAVE DAMAGE IS DONE

By the time women are ready to seek treatment for hair loss, many are emotionally ready to change their hair care practices, but it’s often too late. Several dermatologists I spoke with for this story said women arrive in the office somewhat desperate for a solution; they don’t really have to be persuaded to stop wearing a weave.

There are two common types of alopecia that black women experience: traction alopecia, caused by chronic pulling and tension on the roots, and a condition called central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), a disorder in which inflammation and destruction of hair follicles causes scarring and permanent hair loss.

In both cases the hair follicle becomes inflamed, damaged, and ultimately gets replaced by scar tissue. These types of balding are different from female pattern baldness (androgenic alopecia), which is largely genetic and involves a shrinking of the hair follicle.

Like many health issues affecting African-Americans, there is no history of research and it is hard to have baseline data as to whether the hair loss numbers are greater than ever, or just that more women are becoming aware and seeking out.

In survey research presented at the American Academy of Dermatology's 74th Annual meeting, Dr. Yolanda Lenzy, found that 47.6 percent of African-American women reported hair loss to the crown or top of the scalp. A Johns Hopkins review of 19 studies caused a bit of buzz last year, estimating that one-third of African-American women experience traction alopecia.

Experts agree that genetics play a role, and they said a strong association exists between certain scalp-pulling hairstyles and the development of traction alopecia-- including sew-in weaves, braids, dreadlocks—and even roller sets.

“When you see pustules forming from the tension of braids, for example, that’s a clear sign of inflammation,“ Lenzy says. The infamous “edges” are particularly at risk. “The temple follicles are very delicate. You can look at the follicles under a microscope, and they’re much smaller. The hairline will fall out with same tension that’s applied elsewhere on the scalp.”

Less clear in the causation debate is the compounding effects of years-long practices such as relaxers, hot combing, or haircolor. Some people just have more resilient hair and can do all of these hair practices and never have issues, says Crystal Aguh, M.D., author of the Johns Hopkins review.

Dr. Lenzy says she diagnoses about five African-American women per day with different types of hair loss. Treatment options are not great. The treatment protocol is to try to halt the progression of the disorder. In the early stages, the goal is to stop the inflammation through anti-inflammatory drugs, including antibiotics such as Doxycycline, Topical cortisone, or cortisone injections.

Off-label, many doctors prescribe Rogaine. For patients with later stage alopecia, the results are permanent and the only solution is to cover up with weaves and wigs forever. That's how the slippery slope begins: You notice a balding patch, freak out, and the anxiety and shame causes you to depend on wearing weave even more.

Lenzy believes there may come a day where we think of weaves like we did sunbathing or smoking, practices at one time considered safe before eventually the whole medical community agrees the health risks weren’t worth the beauty or social benefits—at least not without a warning.

CHANGING THE FUTURE OF BLACK HAIR

The state of black hair now is almost the complete opposite. There is very little regulation and consumer protection around styling practices like braiding hair and weave installation (which usually requires braiding the natural hair to contain it under a weave.)

In most states you’re required to have a cosmetology license to shampoo, cut, or dye hair in a salon, but occupational licensure around braiding varies widely. Georgia is one of roughly 20 states that require no specific license for braiders. Here, any person who braids by hair weaving; interlocking; twisting; plaiting; wrapping by hand, chemical, or mechanical devices does not fall within the Georgia Board of Cosmetology governance.

Nationally, there’s a movement to further deregulate braiding practices in the states that have requirements—led in part by the Koch-affiliated law firm the Institute for Justice, which has been lobbying to eliminate braiding licenses in more than a dozen states.

They recently scored a victory when two women Aicheria Bell and Achan Agit – two Institute for Justice clients—filed a civil lawsuit against the state cosmetology board in Iowa. Braiders in the state were originally had to have a cosmetology license, which required 2,100 training hours and could cost up to $22,000 to obtain.

Their argument? Going to school wouldn’t teach them how to braid natural hair anyway, because the beauty schools mostly included training on Eurocentric hair styling. In the end, Governor Terry Branstad exempted braiders from the requirements, and now braiders merely need to register with the state.

Some argue that it’s an economic win for the braiding community: fewer barriers to entry in the profession mean more jobs and more people working. But you have to wonder why are cosmetology schools allowed to focus only on Eurocentric beauty standards—and not required to teach healthful braiding and natural hair practices—when tens of millions of women in America don’t have Eurocentric hair?

Dr. Yolanda Lenzy thinks this is a disservice to consumers and stylists alike. “Even if you’re not relaxing and coloring hair, you need to learn infection control,” she says. “What does ringworm look like? How do you spot early-stage CCCA? If you have a client in your chair, the stylist is the first line of defense.”

As black women, our hair is our crown, but increasingly it feels like the joke is on us. It’s problematic that our society encourages black women to literally go bald to chase an ideal, so that we are permanently purged of the exact symbol of femininity we are chasing.

When it comes to beauty, for me, it always comes back to the daughters. As mothers we constantly ask ourselves what is a healthful practice for our daughters. I want to see my daughters learn to define their beauty and their self-esteem in a manner that is unattached to their hair.

Mentally and physically, weave reinforces the idea that who we are is not enough. I would ask myself, what guidelines exist around safe weave practices? How young is too young to start a weave? How many years are too long to wear one? If she starts as a preteen, will she be bald by the time she is age 30? Right now, no one is asking or answering these questions. Let’s bring some light to this issue, instead of hiding the truth.

*Name has been changed to protect the privacy of individuals