The rocky, wacky origin story of CNN in book form

Nearly 40 years ago, Ted Turner stood on the steps of his Techwood campus in Midtown Atlanta and confidently launched what was then an audaciously quixotic concept: Cable News Network, news 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

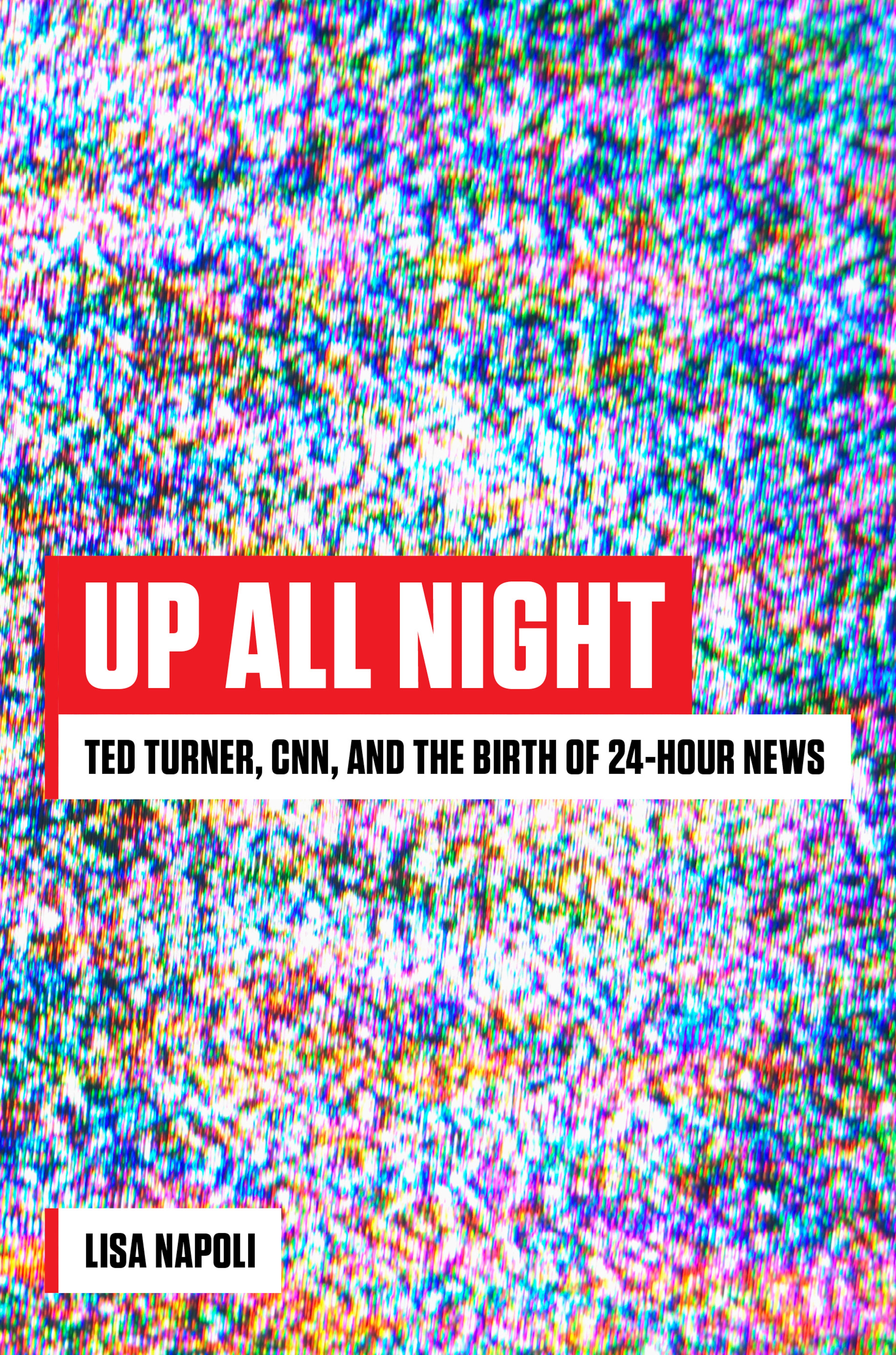

While CNN itself has been mocked, studied and picked apart ad nauseam for decades, journalist Lisa Napoli decided to go back in time to chronicle how CNN came into existence in her new book "Up All Night: Ted Turner, CNN and the Birth of 24-Hour News." (Abrams, $27). It comes out Tuesday, May 12, 2020. (You can buy it here on Amazon.)

The book, at 246 pages minus the index and bibliography, is a breezy, tightly-written origin story which bookends two events: the first “live” TV event in 1949 of a girl stuck in a well and the comparable baby Jessica in a well story in 1987, covered wall-to-wall by CNN.

PHOTOS: CNN, HLN's memorable anchors and faces through the years

Napoli worked at CNN Headline News for a couple of years in the mid 1980s but does not consider herself a true CNN insider, more a curious reporter whose resumé includes the New York Times, NPR and MSNBC. She had just written a bestselling book about Joan and Ray Kroc, who turned McDonald’s into the fast-food king that it is today. This struck her as a worthy follow up.

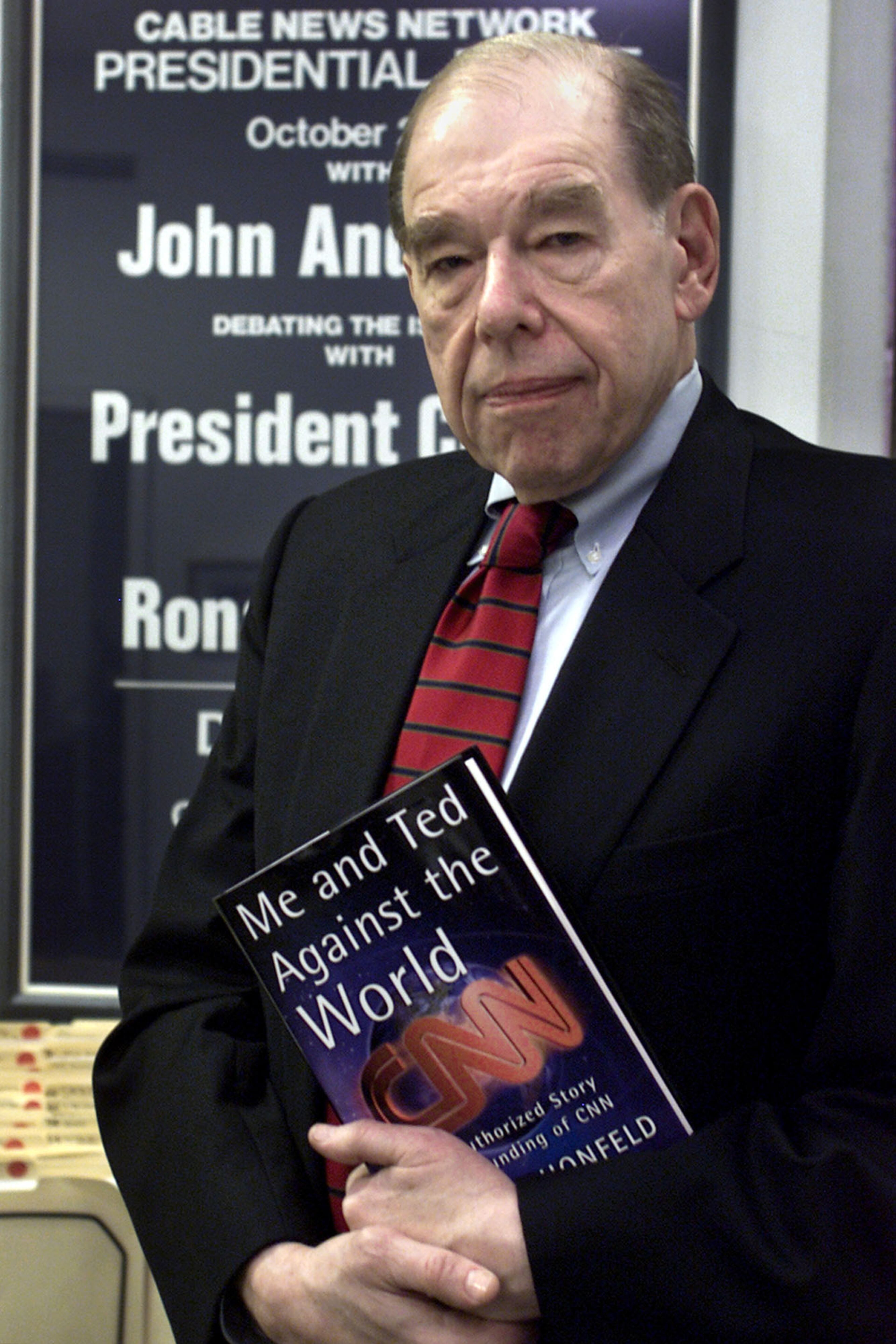

Starting in 2017, she read every book she could find about CNN, Turner and the early years of cable TV and interviewed dozens of players who were still around, including two key people featured prominently in the book: former WTBS newsman and humorist Bill Tush and Turner’s first CNN president, Reese Schonfeld.

Nonetheless, Turner is the star of the book, the raison d’etre, so to speak. Napoli recounts his wild, womanizing, carousing ways, his infectious personality, his innate desire to do things bigger and better.

“How Turner got into the business was interesting,” Napoli said. “The obstacles he faced and the people he assembled were interesting as well. I also merged the history of Channel 17 with CNN. I don’t think anybody thought to do that. Bernie Shaw wouldn’t have happened if Bill Tush hadn’t happened. It was a progression.”

Long before CNN came to be, Turner was not a fan of news, Napoli discovered. He didn’t watch Walter Cronkite. He found the nightly news too depressing. He preferred scripted fare, old movies especially. And he loved sailing. His 1970s yachting exploits are intertwined with his rise in the media world.

When Turner purchased the independent station WTCG (which would become Superstation WTBS), he cobbled together classic films, ancient sitcoms and wrestling as cheaper counter-programming to the big three networks. Because the Federal Communications Commission required “community service” type programming, he gave Tush a chance to do an overnight news show with nearly zero budget.

Tush, one of Turner's early WTCG employees, turned the show into a news farce instead, bringing in Rex the Wonder Dog as his co-anchor and "Red Neckerson" as an analyst. And once Turner was able to beam WTCG to the entire country via satellite, Tush became the first star of the cable universe, fan mail flowing in from all over the country.

As Turner sought ways to expand his empire, he considered sports and music, but he ultimately chose news.

Though CNN’s top brass and talent is now based in New York, Turner at the start “pushed to have CNN in Atlanta, not just because it was convenient for him,” Napoli said. “He felt it was important to have a news source outside of New York and D.C., to be able to provide a wider point of view.”

Turner didn’t pretend to be a newsman. “I don’t know a thing about journalism,” Turner told his new CNN staff before the launch, according to the book. “But I’m betting $100 million that you all do.”

Napoli detailed the crazy nature of the hiring process — a blend of experienced journalists and newbies — and the difficulties of using new technology in a new location from scratch. One joke that went around in 1980: “What’s the difference between CNN and the Hindenburg? At least the Hindenburg got off the ground.”

She noted the challenges of attracting talent from New York to come to Atlanta at the time and the natural skepticism from other journalists and Wall Street about this rag-tag operation working in a basement of a converted country club.

PHOTOS: CNN Center and Turner Broadcasting through the years

For all his bluster, Turner on the day of the launch had an idealistic vision for CNN and even hoisted a flag of the United Nations next to flags of the state of Georgia and the United States.

“We hope that the Cable News Network,” he told the word that day at the dais, “with its international coverage and greater-depth coverage, will bring both, in the country and in the world, a better understanding of how people from different nations live and work together, and within the nation work together, so that we can perhaps, hopefully, bring together in brotherhood and friendship, in kindness and peace the people of this nation and the world.”

Off script, though, Turner loved taking shots at the three networks, calling ABC, NBC and CBS an “oligarchy” propagating sleazy sex and violence, calling the executives a “greedy bunch of jerks” worse than the Nazis.

Surprisingly, the critics were relatively kind about the initial launch of CNN. Tom Shales, the curmudgeon of a TV critic for The Washington Post, said the premiere showed “that CNN means business and that it is anything but the plaything of a playboy. A new day dawned at dusk.”

Still, CNN struggled for a long time. Napoli recounted those fraught early days when reporter Daniel Schorr’s pants caught on fire when a studio light exploded and a switching error transmitted a porn channel instead of CNN for, as she wrote, “a painfully long few seconds.” In its early years, the network was bleeding $2 million a month, subsidized by Turner’s more successful TBS Superstation.

And Napoli spent several pages on Turner’s visit to Cuba in 1982 to meet Fidel Castro, who had become an early fan of CNN by stealing its signal. Bizarrely, Turner asked Castro for a testimonial, which Castro agreed to.

She did not interview Turner for the book but said Turner’s office was helpful in getting her information when she requested it. She also had archives of hundreds of colorful video and print interviews Turner did in the 1970s. “Every newspaper of any size back then had a feature reporter who went out and interviewed Turner,” she said.

Napoli, who is now working on a book about the founding women of National Public Radio, makes it clear this is a straightforward book with no political agenda even as the network today has become a lightning rod for the right and the current president as well.

“People are so polarized about media now,” she said. “I wrote it so people can see what happened and decide for themselves.”