Why Brian Kemp may need some time to find the right words

Brian Kemp is the first governor to have come of age in a post-segregated Georgia. He takes office during one of the most polarized periods – racially and culturally – in our nation's history.

Those two facts formed the basis of the new governor’s inaugural speech on Monday. They are likely to underpin his next four years at the state Capitol, too.

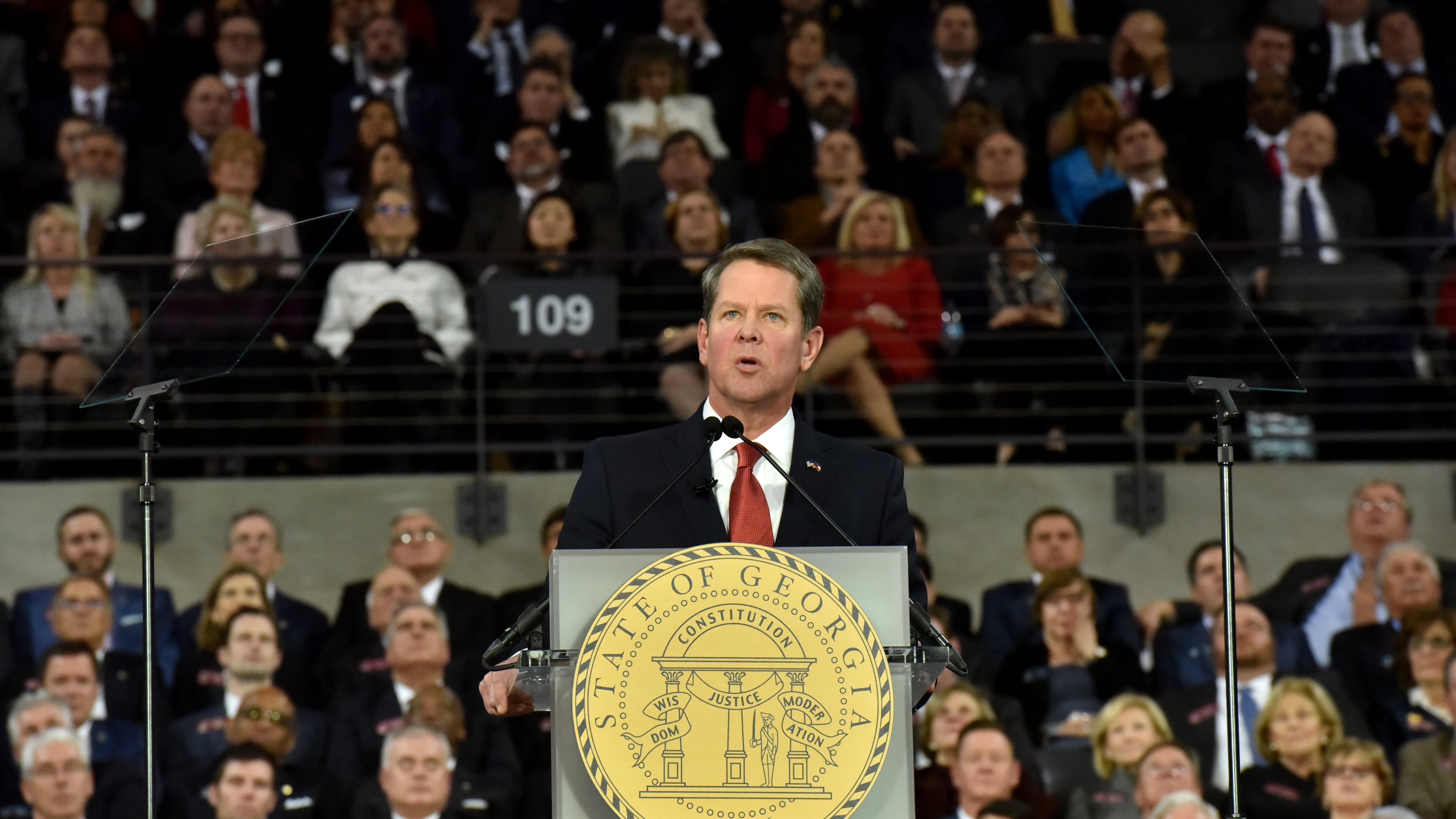

The 55-year-old governor accurately assessed the situation he faces. “Through the prism of politics, our state appears divided. Metro versus rural. Black versus white. Republican versus Democrat. Elections can rip us apart,” Kemp said.

His own part in aggravating that division with a campaign that cleaved rural and urban Georgia went unnoted. Nonetheless, Kemp willingly assigned himself the job of pulling the state together. “We will keep our schools, our streets, and our kids safe. And put people ahead of divisive politics. We will be known as a state united. It can be done,” he told a Georgia Tech arena dominated by older, white Republicans

Where and how he grew up in Athens can guide Kemp toward what needs to be done. But how to do it – how to speak to and touch, in large numbers, that part of Georgia that isn’t Republican – may be something that has been outside his previous political experience. The man needs some time to develop his vocabulary. And we need to give him time to do so.

The opening lines of Kemp’s address were a paean to the “men and women…who poured the foundation for us” – the phrase a self-conscious nod to his own home-building past.

And then he gave us a list. “People like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, Hank Aaron and Herschel Walker. Entertainers like Ray Charles, Otis Redding and Gregg Allman.”

Six of those seven are African-American — so you know where Kemp was trying to go. On the other hand, save for King, none of those names are likely to be on the tongues of anyone under 35. And perhaps including the name of at least one Georgia woman might have been helpful.

Yet, another omission probably did Kemp some good: The name of President Donald Trump was left out of his address.

As mentioned above, Kemp graduated from Clarke Central High School in 1982. Integration and busing had arrived in Athens in 1969, with a few demonstrations and one or two outbursts, but little to no violence — thanks in large part to the influence of University of Georgia faculty members who were also parents, a 1970 Southern Regional Commission report indicated.

If there was a chronic hot spot in the Athens fight over integration, it was high school football. “One Monday, late last October, after the integrated Clarke Central team had lost its only game of the season, a group of black players refused to practice. They claimed that the head coach had unfairly blamed them for losing the game,” the SRC report noted.

At the time, three private schools operated in Clarke County. There was a Catholic parochial school that accepted black students. Two other schools were all-white: Athens Academy, which was described as a K-12 “college preparatory” school in the SRC report, and Athens Christian Academy. The latter, the report implied, was one of more than a hundred private “segregation” schools that opened in response to judicial desegregation orders.

Kemp went to the Athens Academy until the ninth-grade, when he shifted to Clarke Central – presumably to play football for Billy Henderson, the coach who would become the hero in Monday’s inauguration speech. Henderson had arrived in 1973.

“Coach realized quickly that the Gladiators football program had talent. But they weren’t a team. In the wake of desegregation, Clarke Central was still divided on racial lines,” Kemp said. “Coach took the football team to Jekyll Island for pre-season camp. They came back as brothers.”

In case you missed the 2000 movie, that’s also the plot line for “Remember the Titans” — but with Denzel Washington as the coach.

This is where Kemp says he would like to take us, metaphorically speaking. Unfortunately, we can’t all fit on Jekyll Island. So the governor must come to us — and this is where Kemp’s talent for adaptation will be tested.

Kemp may be the first Georgia governor to grow up in an integrated South, but he is something else, too. He is Georgia’s first pure-bred Republican governor.

To Sonny Perdue and Nathan Deal, Republicanism was a second language. When the situation called for it, they could speak fluent Democrat. Kemp’s political career began with his election to the state Senate in 2002. It coincided with the collapse of the biracial coalition that had kept Georgia Democrats in power far longer than in any other state in the South.

Since Perdue’s victory in the 2002 contest for governor, Georgia has been governed through the prism of a Republican primary. Like many other of his fellow Republicans who now hold the reins of state government, Kemp has never had to speak Democratic.

But when you win the Governor’s Mansion with 50.22 percent of the vote, it may be time to become bilingual. Which will require effort on Kemp’s part, and patience on the part of those whose outrage still simmers.

On Monday, after the new governor had left, a UGA wind ensemble played the crowd out of the Tech arena. Word quickly spread that some had heard the tune “Dixie” – which has been barred from Georgia football games since the early 1970s.

Well, it was true.

A solo trumpeter had indeed played a few bars of “Dixie.” Seven or eight at most. But the air was a very small part in a large composition – the dominant melody of which was something entirely different: “As We Were Marching Through Georgia.”

That was the tune sung by Billy Sherman’s troops as they walked from Atlanta to Savannah, putting the Confederate war machine to the torch.

In other words, context is important. It may be time to sit back and listen to the larger tune that Kemp is about to play.