Gov. Brian Kemp's order to begin reopening a state economy battered by the coronavirus is set to take effect Friday, the same day that Operation Gridlock, a Fox News-endorsed protest against shelter-in-place policies, intends to wrap its arms around the state Capitol.

The vehicle-based parade– call it a white version of Freaknik — now has an opportunity to become a victory celebration by a group of (presumed) voters whom Georgia Republicans will need in November.

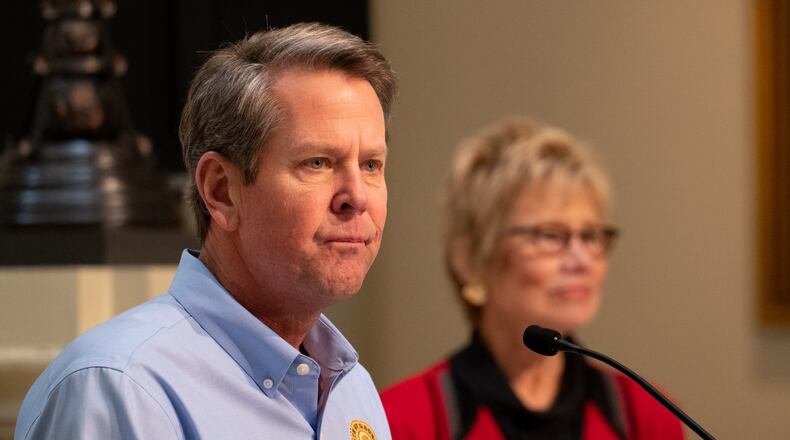

On Monday, sharing the microphone and endorsing the Kemp plan were the two other top Republicans in the state Capitol, creating a united GOP front: House Speaker David Ralston and Lt. Gov. Geoff Duncan. Missing was the governor’s most prominent Democratic (and African American) partner in pandemic policy, Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms.

And yet Governor Kemp declared this to be his politics-be-damned moment. I will not contradict him. The facts will have to carry that burden.

Gyms, fitness centers, bowling alleys, body art studios, barbers, cosmetologists, hair designers, nail care artists, estheticians, and massage therapists – all occupations dealing in shared equipment or intimate human-to-human contact – will be allowed to operate as of Friday. Per the governor’s order, restaurants and movie theaters will be allowed to open Monday. And yet the mayor of the state’s largest city was not worth consulting. It’s clear why.

“I’m extremely concerned about the announcement the governor made. I hope that he’s right and I’m wrong, because if he’s wrong, more people will die,” Bottoms said during a shelter-in-place interview Monday night.

Possibly, the governor is right. Perhaps this is not a political occasion. But if not, then it is an intensely philosophic moment writ large. In 72-point type. And to be fair, it is reflective of the man Brian Kemp said he was when he applied for the job of governor.

His 2018 contest with Democrat Stacey Abrams was largely about health care. That September, at a gathering of the state’s business community, Abrams endorsed an expansion of Medicaid, which would give health insurance coverage to hundreds of thousands of Georgians, as necessary for the rescue of rural Georgia. Jobs won’t go where there are no hospitals, she said.

Kemp took the opposite tack. “If you don’t have a tax base in rural Georgia, if you don’t have people that are working there, it’s going to be hard to support a local hospital,” he said. If you read Candidate Kemp’s words carefully, you will see an acknowledgement that the sacrifice of a certain amount of human capital is necessary to bring the economic engine up to speed.

Jobs first, and only then health care. A coronavirus pandemic merely puts these brushstrokes on the largest canvas possible. At the heart of this approach is the preservation of an employee-based health insurance system – which was leaving more and more people without coverage well before the pandemic struck.

But the alternative is government coordination, and that’s where our governor blanches, even now.

Last week, even as he bemoaned a lack of testing that would show us the extent of infection in Georgia, the governor said the ultimate solution wouldn’t be found at the state or federal level.

“We can definitely do more than we’re doing,” Kemp told reporters. “We can definitely help, but we need the private sector to step up. We need to have a test where people can basically immediately test themselves before they leave the house and go to work.”

“The government, in my opinion, is not going to be the answer,” he said.

On Monday, the governor showed the appropriate deference to the social distance and sanitation demands of public health officials.

“I think our citizens are ready for this. People know what social distancing is. They’re learning what mitigation was when we went through it.” Kemp said. “And they’re fixing to learn a lot more about contact tracing, which is a big part of the next step.”

But the governor saved his passion for one particular group. “I don’t give a damn about politics right now,” he said. “We’re talking about somebody who has put their whole life into building a business, that has people that they love and work with every single day – working in many of these places.”

Of course, there are other people who have put their whole lives into their whole lives. They will have to be judicious, even as experts now tell us that the virus lives asymptomatically in far more people than they once thought. Even the governor acknowledges this now.

“Listen, the private sector is going to have to convince the public that it’s safe to come back into these businesses. We’ve seen some very innovative people out there making those changes to their business practices,” Kemp said. “That’s what a barber’s going to have to do. It’s what a hair salon is going to have to do. It’s going to have to be what a tattoo parlor is going to have to do.”

Possibly a tattoo artist will invent a six-foot needle. In any case, the all-clear signal apparently won’t come from our governor, but from a business owner looking to make the month’s rent.

In the midst of all this, I put in a phone call to Bill Custer, an associate professor at Georgia State University and well-known expert on the nation’s health care system.

I asked him about Kemp’s idea to put the testing onus on businesses. Custer worries about higher premiums to come, which would mean even fewer workers with insurance coverage. And about lawsuits.

“Everybody is guessing what the end game is going to look like – exactly how things are going to look coming back together,” the academic said. “It’s hard to imagine that many small businesses are going to be able to risk coming back too soon. They’re going to be subject to an incredible number of lawsuits if people get sick.”

And putting testing in the hands of businesses – for both workers and customers? “That’s a non sequitur — because it’s the government that’s subsidizing and helping produce these tests and certifying that they’re accurate enough,” Custer said.

Privatizing pandemic detection would make test kits the objects of bidding wars and raise questions about quality and accuracy.

“The premise is that if we’re in a war-time footing, you need to have basic ammunition, and that can only be provided on a national level by a national effort,” Custer said. “Jane’s Software Co. simply is not going to be able to bear those costs directly. I understand the impulse — if you think the private market’s always better. But it’s not always better, in many situations.”

Pandemics being one of them.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured