There is nothing like a global pandemic to underline a community's dependence upon the strangers in its midst, regardless of status.

The numbers are a bit dated, but in 2016 the Pew Research Center put the number of unauthorized immigrants in Georgia at 400,000 — with 275,000 in metro Atlanta. They have provided much of the labor behind the region’s construction boom, yet spend their off-hours in the shadows.

Shadow-dwellers become a problem in a pandemic. These are people who will be slow to seek out tests or medical treatment. They have gone unmentioned in outlines of Gov. Brian Kemp’s coronavirus task force. Possibly, outreach to unauthorized immigrants will fall under the purview of Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottom, whom the governor has assigned to lead the “Committee for the Homeless and Displaced.”

On the other side of this coin are the authorized visitors. In 2018, Georgia agriculture employed 32,364 workers here on temporary H2-A visas — more than any other state, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. Last week, it was announced that the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City and all U.S. consulates in Mexico would suspend routine immigrant and nonimmigrant visa services.

If you’re a South Georgia farmer, there are two beads of sweat on your forehead. One is for the coronavirus and what it might do to friends and family. The other is a drip, drip, dripping worry that the next weeks and months could see crops rotting in fields.

In this new age of social distancing, journalism has become a series of phone conversations and Facebook Live chats. Let me walk you through the ones I made on Monday and Tuesday.

My first call was to Charles Kuck, one of the more prominent immigration attorneys in metro Atlanta. He pointed to a recent change in immigration policy by the Trump administration that’s likely to affect local efforts to control the pandemic. The “public charge” rule, published in August by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, establishes a test to determine whether an immigrant is likely to end up accepting public benefits. It’s meant to discourage low-income immigrants.

Acceptance of any public assistance could jeopardize an application for a green card or later, citizenship. President Donald Trump said in a press conference Sunday that unauthorized immigrants could have free access to tests for the coronavirus. Kuck has assured his clients of the same. But “free” is not the point.

“They’re not going to get tested. Because of the public charge rule that Trump put in, they’re all afraid to use anything that would reflect negatively upon them in the future,” Kuck said. “It’s a nightmare. It’s a public health nightmare. When you marginalize people, then you have all the consequences that come from that.”

Something the coronavirus hasn’t changed is the implacable effort by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to sort through those claiming asylum or otherwise disputing federal efforts to deport them. Other courts, at the federal and local level, may have suspended activity.

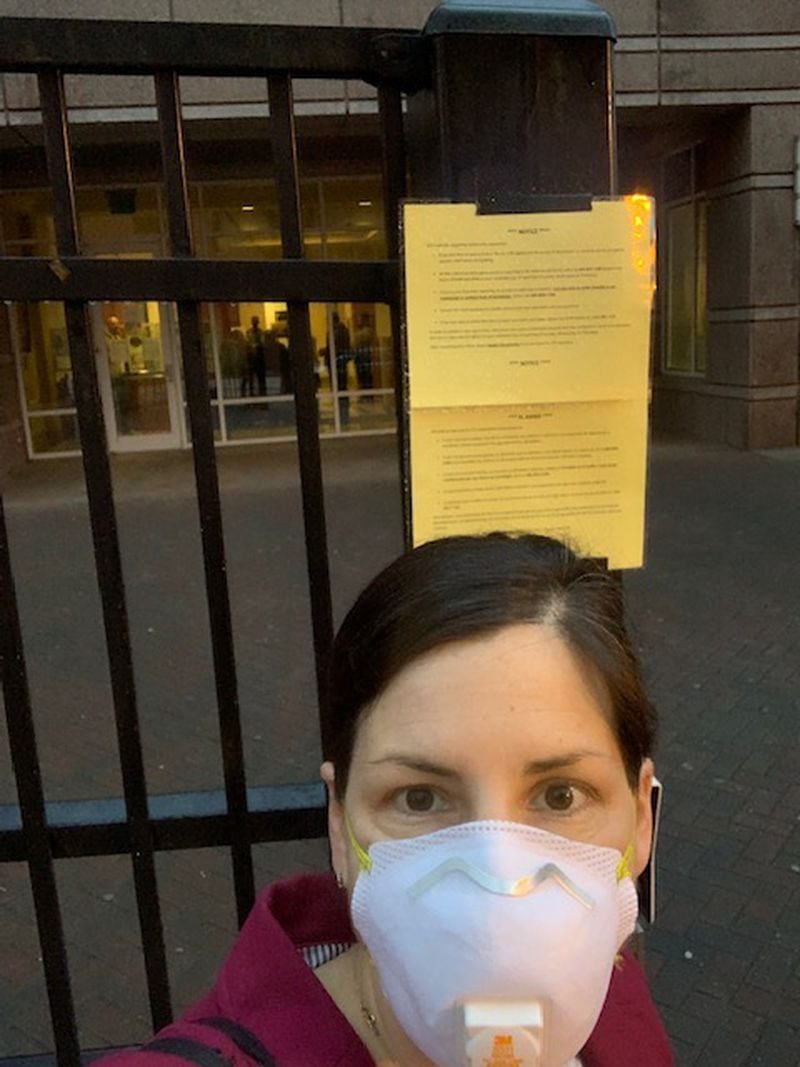

“The immigration courts in our detention centers are still operating,” Kuck said. “But if you as a lawyer want to appear on behalf of your client, you have to come in your own personal protective gear — including eye shades, a mask, gloves and a gown. If you don’t dress like that, you can’t come in and you can’t object to any documents introduced against your client.”

Kuck later sent the selfie of a masked law partner, Danielle Claffey, about to enter an immigration courtroom in Atlanta.

My next phone call was to Rebekah Cohen Morris. She was recently elected to the Doraville City Council but is also housing director for Los Vecinos de Buford Highway, an organization that gives voice to apartment dwellers along that road.

“Ninety percent are undocumented,” she said. “There’s a constant conversation happening. People are obviously scared. A lot of the men are still working.”

The good news, from her point of view, is that ICE strikes have declined. “A lot of immigration officers aren’t out doing raids at this point,” Cohen Morris said.

The bad news is that April 1 is fast approaching. That’s when the rent is due. “We have a rent assistance fund. We opened it — and within one hour we had 27 applications. And we only have, like, $3,500,” she said.

None of these people live in federally subsidized apartments. None are eligible for any public services at all. So Cohen Morris expressed appreciation for DeKalb County CEO Michael Thurmond’s emergency declaration that puts a lid on evictions.

Call No. 3 was to U.S. Rep. Austin Scott, R-Tifton. Last week, Scott and U.S. Rep. Doug Collins very politely wrote Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to express “concern over inadvertent delays in processing H-2 agricultural guest workers.”

The delays, they wrote, could have a “negative impact” on the nation’s food supply — never mind the damage that it could do to a South Georgia economy still reeling from Hurricane Michael’s visit to the state in 2018.

Scott doesn’t want to pick a fight with the Trump administration. He understands that U.S. diplomatic workers in Mexico are overwhelmed by the effort to bring U.S. citizens back home.

“Things that would have been very simple a month ago are very hard right now. It is simply because of the amount of work exceeding the capacity,” Scott said. “But I do think if delays continue, we’re going to see crops rotting in the field.”

It’s a paperwork issue, the congressman said. “They have to renew these visas every 12 months. The farmers know these people. The same people come to work these farms every year. There’s a process here that’s followed,” Scott said. “There’s a timeline that gets them here to pick the vegetables. And that timeline has been disrupted.”

And it is vegetable farmers who would be hit first and hardest. “On vegetables, they really don’t have a crop insurance program — not like cotton or peanuts,” Scott said. “So it’s just a loss.”

Squash is being picked now.

The congressman gave me the phone number for Bill Brim, a local farmer. He was my last call.

Brim farms 6,500 acres of vegetables, 1,000 acres of cotton and peanuts, and 85 million pine tree seedlings. (He did not explain how he counts that last crop.)

Over the course of a year, Brim will employ 450 seasonal out-of-country workers. All on H2-A visas. Workers are recruited by brokers, but as mentioned earlier, many are repeat visitors. Between 30% and 40% of his workforce is in jeopardy.

One group of 145 or so workers has arrived, but two of the workers were found to have bad paperwork. They’ve been sent home, but a U.S. agency wants all the others returned home, too. Brim has so far declined, and he has asked members of Congress, including U.S. Sen. Kelly Loeffler, to intercede.

But wait, there’s more. “I’ve got 57 people down there on extensions, that went down there to see their family," Brim said. "They can’t get back.”

They are wrapped up in the coronavirus chaos at the border. Which means Brim is, too. Along with you and your grocery store.

About the Author