Opinion: That time when a governor’s friends didn’t respect his U.S. Senate pick

Once upon a time, there was a newly elected governor of Georgia who picked a wealthy political novice from Atlanta to fill a sudden U.S. Senate seat vacancy.

Lo and behold, and to much wonderment, one of the governor’s friends did not consider this choice a sacred thing, and at the first opportunity attempted to undo what the state’s chief executive had wrought.

You can be forgiven for thinking this to be the tale of U.S. Sen. Kelly Loeffler, U.S. Rep. Doug Collins, and their quest for President Donald Trump’s love and favor. But it’s not.

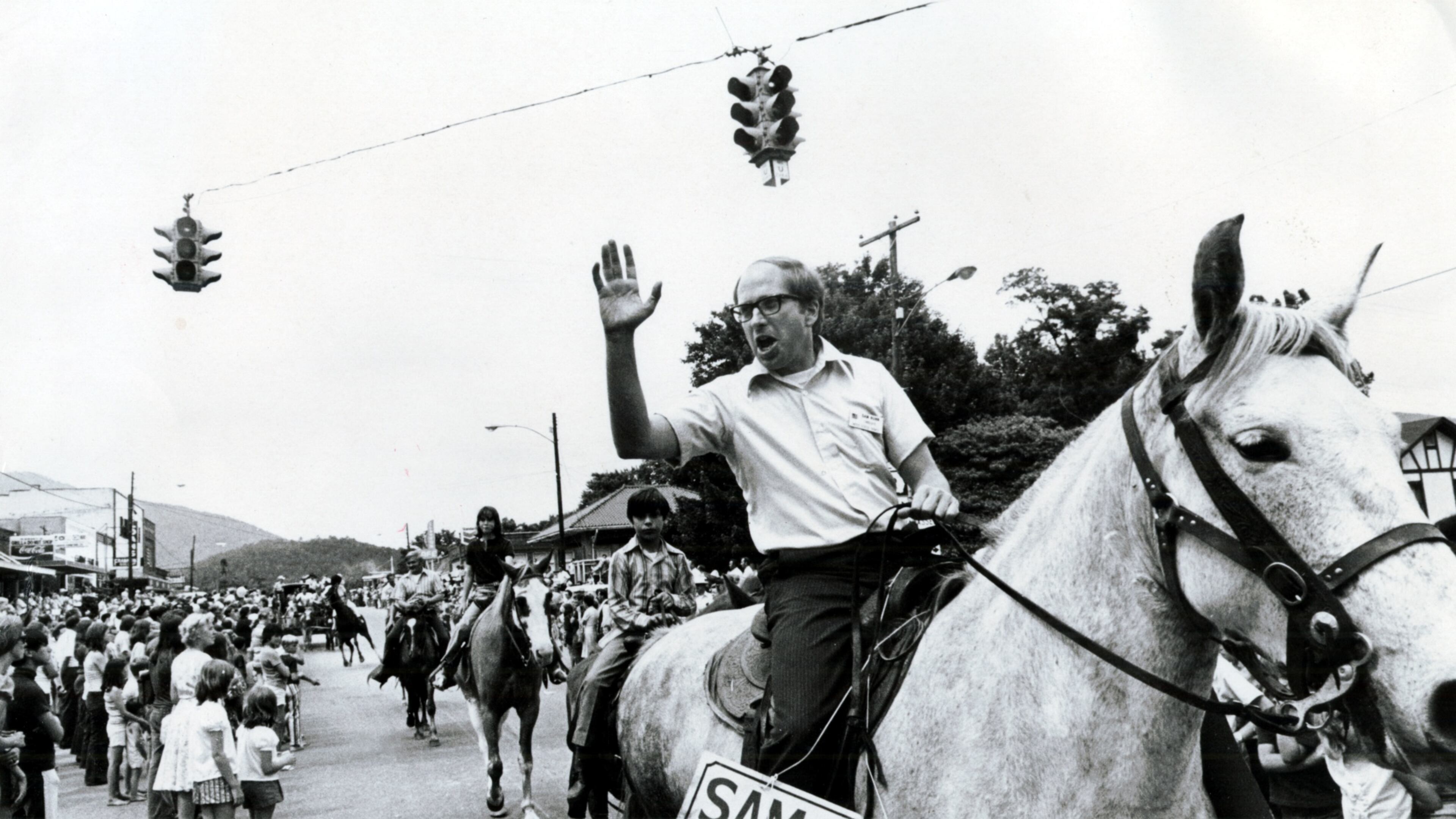

This is the story of how, nearly 48 years ago, state Rep. Sam Nunn became U.S. Sen. Sam Nunn. It doesn’t match perfectly with the current situation, but there are similarities worth pointing out. And a few interesting nuggets that may or may not have relevance.

For instance, in the archives of the University of West Georgia, we found a 28-year-old confession from the man whom a governor had picked, and Nunn had defeated.

“This is one of the problems with being appointed,” he said. “I knew this from the beginning – that the casualty rate among appointed senators or appointed anything was very high. And my chances of being elected in the election were poor.”

On Jan. 21, 1971, nine days after Gov. Jimmy Carter had been sworn into office, Richard B. Russell succumbed to emphysema at age 73. He was the most senior member of the U.S. Senate, and had long served as leader of the South’s congressional bulwark against integration.

There was no internet, and so no three-month contest for the job like the one Gov. Brian Kemp held last year. Ten days after Russell breathed his last, David Gambrell was sworn in as the junior U.S. senator from Georgia – joining Herman Talmadge in the chamber.

Gambrell had served as Carter’s campaign treasurer in the recent campaign. He was well-connected, a graduate of Harvard Law School and a former president of the state bar, but Gambrell’s appointment to the U.S. Senate was still something of a surprise — given that he’d already been rewarded with the chairmanship of the state Democratic party.

He had never held office before, but the next year, Gambrell was required to stand for election to a full six-year term. There would be no all-comers election, as Loeffler faces on Nov. 3 – in which all Democratic and Republicans challengers will appear on the same ballot.

But the rhythm of 2020 could have much the same feel as 1972 – a first vote that will involve a large slate of candidates, and a final vote that pits a rising Southern party against the one in power.

In 1972, the two biggest Carter critics of the day, on opposite sides of the political spectrum, were former Gov. Carl Sanders and Lester Maddox, the former segregationist governor who was then lieutenant governor. Both stayed out of the Democratic primary.

Fourteen others did not. They included former Gov. Ernest Vandiver, who thought the U.S. Senate job had been promised to him, and overt racist J.B. Stoner, who would later be convicted for the ’58 bombing of a black church in Alabama.

And there was Nunn, then an obscure state House member from Perry.

Many of those involved in that campaign are still active, including both Nunn, 81, and Gambrell, 90. Nunn was out of pocket, and Gambrell, who still maintains a law office, demurred. But we were able to tap a nearly four-hour videotaped interview with Gambrell, conducted in 1992 by the late Mel Steely, a University of West Georgia political scientist.

“There were so many people in it, it was hard to tell exactly how it would come out,” Gambrell said. “When it was first announced that Nunn was going to run, the reaction I got from some of our staff people was, ‘What in the world does he think he’s doing?’ And ‘why is he butting into this?’”

Gambrell said he told his staff that he considered Nunn his most dangerous opponent. “Because he’s supposed to be our friend,” he said.

In fact, Nunn and Carter had been tight, and Nunn’s decision to enter the race created a great deal of turbulence. “Nunn had been very close to Carter, and had been involved in [Carter’s] early campaigns, in ’66 and in ’70. In fact, people thought Nunn was too closely associated with Carter,” said Roland McElroy, who was then a 27-year-old radio journalist from Valdosta.

He would join Nunn’s campaign staff, and would later serve as the senator’s press secretary.

But there were limits to the punishment that Governor Carter could mete out to any challengers faced by Gambrell, and that is one of the key differences between 1972 and 2020. Carter was limited to a single four-year term. As soon as he was sworn in, he was a lame duck.

Brian Kemp is at the front end of what could be eight years as governor. His ability to protect Kelly Loeffler, to persuade supporters of Doug Collins to think twice, is far greater.

The summer primary resulted in a runoff between Gambrell, who came in first, followed by Nunn. Vandiver finished third. Civil rights leader Hosea Williams came in fourth, and Stoner, the racist, was fifth.

The South was changing, and many voters in the runoff campaign were nervous. The Democratic National Convention had chosen George McGovern to run against an incumbent President Richard Nixon.

Gambrell didn’t attend the gathering, but was nonetheless pegged as a moderate. Lester Maddox, who endorsed Nunn, referred to Gambrell as a “liberal” and “aristocrat.” (Julian Bond endorsed Nunn as well.)

Gambrell called himself an “aggressive pragmatist.”

“People were uncomfortable with someone who was different. I wasn’t like Russell, I wasn’t like Talmadge,” Gambrell said. But experience – the ability to put together a campaign and a message — was also a factor.

“[Nunn] had a lot of friends in the Legislature, and he wound up with a better political organization. He had most of the enemies of Carter. He had a bunch of my friends who were his friends, that preferred him over me,” Gambrell said. “The real difference between him and me on most issues was very slight. I think the fact that he was a country boy and I was a city boy made some difference.”

Again, it’s worth pointing out differences between then and now. The 1972 campaign was strictly regional, a reflection of the racial turmoil of the time. Georgia voters put a heavy emphasis on Senate contests, where Southern Democratic power had been lodged for better than a century.

Current U.S. Senate contests have a more national cast. President Trump and Fox News set the message for Republicans, MSNBC and (for now) Nancy Pelosi do the same for Democrats. The Russians do their best to confuse everyone.

The sums of money that float modern contests would appall anyone from 1972, as would the language.

One of the tools that Nunn used to defeat Gambrell was a TV ad that implied that Gambrell had purchased his U.S. Senate appointment. “That ad did the job. It established [Nunn’s] independence from Jimmy Carter,” said McElroy.

But it ran only once. That’s because Nunn’s mother called her son to express her disappointment. The ad was quickly pulled.

In the Democratic runoff, Nunn beat Gambrell with 54% of the vote. This is where the real lesson for modern Republicans might lie.

One outcome of the all-comers U.S. Senate race in November could be a Jan. 5, 2021 runoff between Loeffler and a Democrat – perhaps the Rev. Raphael Warnock, pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church. Or Collins and a Democrat.

Nearly 48 years ago, after the Nunn upset, Gambrell, Carter, and the entire Georgia Democratic establishment quickly buried their differences and backed him in the general election.

Nunn faced Republican Fletcher Thompson, a congressman who had become the leader of anti-busing forces in Atlanta. And President Nixon was implementing his Southern strategy to lure white voters into the GOP camp.

The ticket posed an existential threat to Georgia Democrats then. Many Republicans think the same of Stacey Abrams and her friends today.

Nunn beat Thompson with 54% of the vote – not bad, given that Nixon carried the state. But in the process, Nunn also became the first Georgia Democrat elected statewide without majority support from Georgia’s white voters.

It was an important clue that pointed to where this state was headed.