Gov. Brian Kemp postponed an annual trip to Los Angeles to promote Georgia's film industry on Tuesday as a growing number of movie executives and celebrities criticized his decision to sign the anti-abortion "heartbeat" bill into law.

Abortion rights activists had threatened to protest the May 22 event, and Georgia film executives were worried that tepid turnout and no-shows from studio chiefs could do lasting damage to the state’s movie-making business.

Kemp spokesman Cody Hall said that the trip would now take place in the fall, and that the governor plans to soon tour Georgia film production firms and meet with employees to show support for the industry.

The delay is the latest sign of how quickly the fallout over House Bill 481, which outlaws most abortions as early as six weeks, has rocked Georgia’s film industry since the Republican signed it into law a week ago.

The annual event in Hollywood is usually a cause for celebration, drawing the state’s top officials and big-name film executives to a ritzy hotel. In past years, Gov. Nathan Deal used the occasion to thank studio chiefs and actors for their business.

The relationship between conservative state leaders and left-leaning Hollywood elite has persevered through other rifts, including threats from major studios to ditch Georgia over the “religious liberty” measure that Deal eventually vetoed.

But Kemp’s support for the abortion restrictions has sparked slow-boiling outrage.

Several film production companies have vowed not to shoot anything in Georgia, and dozens of actors including Alec Baldwin, Don Cheadle and Sean Penn signed a protest letter saying they won't work in Georgia because of the law.

One of the first to call for a boycott, “The Wire” creator David Simon, said shortly after the law was signed he will “pull Georgia off the list until we can be assured the health options and civil liberties of our female colleagues are unimpaired.”

Others have taken a different tack: Jordan Peele and J.J. Abrams will shoot an HBO horror drama in Georgia but will donate fees to the ACLU and the Fair Fight Action group founded by Stacey Abrams, the Democrat defeated by Kemp in November.

The Motion Picture Association of America, which represents Netflix and other leading studios, is taking a wait-and-see attitude. In a statement, the group pointed to similar legislation adopted by other states that was blocked in the courts.

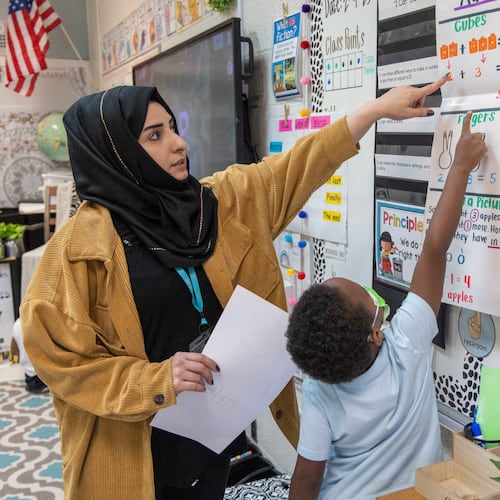

Credit: Emily Haney

Credit: Emily Haney

A timely delay?

A legal challenge in Georgia, too, is inevitable. The ACLU and other opponents plan to file a lawsuit this summer, and conservative backers of the law hope it will wind up in the U.S. Supreme Court to test the Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion.

Georgia film boosters hope that when the “Film Day” event is held in Los Angeles later this year, the legal challenge helps cool the heated debate over the law.

“Oddly, I believe the governor will be better received in Hollywood once the ‘heartbeat bill’ moves to another branch of government for judgment,” said Kris Bagwell, chairman of the Georgia Studio and Infrastructure Alliance.

Lee Thomas, the deputy commissioner of the Georgia Film Office, said in a memo to local production executives that the event was delayed due to “numerous factors” and likely would be held in November.

Georgia has become one of the leading locations for movie and TV productions thanks to a lucrative incentives signed into law in 2005 that allows film companies to earn tax credits for up to 30 percent of what they spend here.

In fiscal year 2018, 455 productions were shot in Georgia with an estimated economic impact of $9.5 billion. The state celebrated "Film Day" in March, and state leaders routinely attend premieres of movies shot in Georgia.

The industry has become so influential in state politics that even the fiercest fiscal conservatives see the tax credits as untouchable. That includes Kemp, who said during the campaign he would review every tax incentive except for the film breaks.

Still, the governor said in a recent interview he would not be deterred from supporting socially conservative legislation by threats from the movie industry.

"I can't govern because I'm worried about what someone in Hollywood thinks about me," Kemp said.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured