COOPERSTOWN, N.Y. -- John Schuerholz took an established Atlanta business and made us – and not just us; everyone who followed baseball – care about it in a way nobody ever had. Before he showed up, the Braves were a civic joke. He arrived in October 1990. For the next 15 years, nobody laughed at Schuerholz's Braves.

Speaking to this reporter on April 11, 1991, Schuerholz said: “It was fairly evident that there was no pride in the organization. ... There was an apathy here, and from the outside there was the view that what was going on was acceptable. That’s a belief that has changed dramatically.”

If Schuerholz hadn’t accepted Stan Kasten’s repeated offers – it took several; the guy kept changing his mind – to be the Braves’ general manager, the sport would still remember him as one of its best and brightest. Under Frank Cashen, Harry Dalton and Lou Gorman, he helped make the Baltimore Orioles, his hometown club, into the first colossus of the post-Yankees empire. In Kansas City, he worked to turn an expansion team into a perennial playoff qualifier and, as GM in 1985, World Series champs.

What he did with the Braves remains a source of awe. Over his first 14 completed seasons, Schuerholz’s team finished first without fail. Fourteen times running, the Braves left spring training and played beyond the 162nd game. No team had done that. Maybe no other team will. “The significance of that, the uniqueness of that, it separates itself,” Schuerholz said Saturday.

The team changed over time – not one Brave played in all 14 postseasons – but the greatest pairing in the history of baseball kept doing its voodoo. Schuerholz built the roster; Bobby Cox won with it. The latter was enshrined in baseball’s Hall of Fame three years ago. The former will have his moment Sunday.

Memory lane: The first scheduled game of Schuerholz’s first Braves team was rained out. Their opener was set for April 10, 1991. A crowd of 46,000 – the non-game was announced as a sellout – gathered. It would have been the Braves’ biggest gate since July 4, 1986, and it would have come on an opening night for a team that had, over its past five seasons, finished last four times and next-to-last once.

That would become the giddiest season in the history of Atlanta sports, but nobody had any inkling of worst-to-first on April 10. The Braves’ offseason signings had been prudent – Terry Pendleton, Sid Bream, Rafael Belliard – but none was a splash on the order of Bruce Sutter (signed in 1984) or even Nick Esasky (November 1989). Those 46,000 folks came to Atlanta Fulton-County Stadium that rainy Tuesday because of Schuerholz, who wasn’t just the new sheriff in town, but a sheriff wearing a tie and suspenders.

From his moment of arrival, it was clear he hadn’t said yes to Kasten just to make a few trades and take early retirement. Schuerholz came to Atlanta to set right an organization gone wrong. True, Cox-as-GM had collected some young pitchers and drafted Chipper Jones, but nothing about the Braves filled anyone with confidence. When the team held a night of appreciation for the beloved announcer Ernie Johnson Sr. in 1989, the Braves were so shocked by the turnout that some ticket-buyers spent the first five innings in line at will call.

Enter Schuerholz (and suspenders, which were featured in offseason print advertising). Enter a guy whose message from Day 1 was, “We are a professional franchise and will comport ourselves as one.” He learned from gifted men in Baltimore and K.C., but Schuerholz was never anything less than painstaking. (Heck, he’d taught junior high English.)

When Cox, whose 1976 season as manager of the Triple-A Syracuse Chiefs had ended, was assigned by the Yankees to scout the Royals in September – the two would meet in the ALCS – he asked what to do. “Talk to John Schuerholz,” he was told.” Schuerholz was then K.C.’s director of scouting. The first time these two Atlanta titans met, one handed the other a stat pack and a media guide and led him to his seat at Kauffman Stadium.

For the record, the two Hall of Famers played golf together here Saturday morning. “Horrendous,” was how Schuerholz described his front nine, whereupon Cox coached him up. The back nine? “Spectacular.”

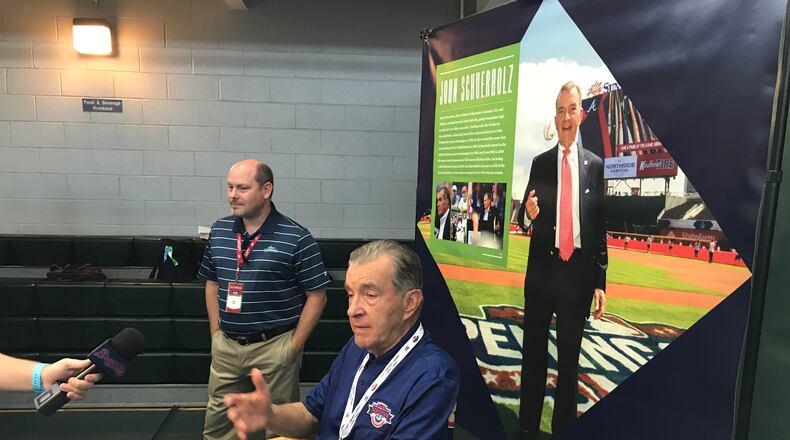

Schuerholz arrived for his scheduled media briefing wearing loafers without socks. (He promised not to go sockless for the induction.) He sat in a canvas director’s chair, saying he felt “like Cecil B. DeMille.” He said he had been here for more than dozen HOF inductions and loves Cooperstown: “It looks like Norman Rockwell designed it.” Still, he conceded, this did feel different. This time he’s the inductee.

Asked about that rained-out sellout in 1991, Schuerholz said: “It rained like it was the end of the world. It was rain above your ankles.” (He remembers everything about everything.)

Did the about-to-be-inducted Hall of Famer ever view that surprising crowd as something that happened because of him? “The fans were ready,” he said. “They thought we had an opportunity to be better. That proved to be right, though the second half (of the ’91 season) was better than the first. That was the starting point … (The fan response) might have been about my style, my background. It was different from what might have been the case before. But it was not about me.”

Wrong. It was. A man came from Baltimore and Kansas City and taught Atlanta how to win, how to keep winning, how to act as if winning was your birthright. John Schuerholz changed the Braves from an amateurish aggregation into the envy of baseball. People saw his haircut and his suits and especially those suspenders and said, “This guy means business.” And he did.

For Sunday’s ceremony, he was asked, would he wear suspenders? “Not unless I make a trip to the department store tonight,” Schuerholz said. “Suits today are not made with buttons inside the pants. And I refuse to wear the clip-ons.”

Of course he does. Clip-on suspenders are for Bozo the Clown. John Schuerholz has never been anyone’s clown. He always carried himself like a Hall of Famer. On Sunday it becomes official.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured