Ga. lawmaker: KKK made 'people straighten up'

State Rep. Tommy Benton is an unapologetic supporter of Georgia's Confederate heritage.

He flatly asserts the Civil War wasn't fought over slavery, compares Confederate leaders to the Founding Fathers and is profoundly irritated with what he deems a "cultural cleansing" of Southern history. He also said the Ku Klux Klan, while he didn't agree with all of their methods, "made a lot of people straighten up." (Read the AJC's latest coverage here.)

Benton's views are why for years he has pushed legislation that would protect the state's historical monuments from being marred or moved. This year he is stepping up his efforts with two newly introduced measures, one of which seeks to amend the state constitution to permanently protect the carving of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Gens. Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson at Stone Mountain.

House Resolution 1179, which Benton, R-Jefferson, dropped in the House "hopper" Wednesday, assures that the "heroes of the Confederate States of America ... shall never been altered, removed, concealed or obscured in any fashion and shall be preserved and protected for all time as a tribute to the bravery and heroism of the citizens of this state who suffered and died in their cause."

It also requires the park around the mountain to be kept as "an appropriate and suitable memorial for the Confederacy."

If passed, the resolution would go to voters as a statewide referendum before it could be added to the constitution.

Benton also is behind a second bill, House Bill 855, requiring the state to formally recognize Lee's birthday on Jan. 19 and Confederate Memorial Day on April 26. State employees have long received these as paid vacation days, but this year Gov. Nathan Deal had them listed on state calendars as generic holidays.

Benton said his bills are a direct response to Senate Bill 294, which would forbid the state from formally recognizing holidays in honor of the Confederacy or its leaders. Benton described the bill's sponsor, Sen. Vincent Fort, as "a fanatic" and the bill's intent as "cultural terrorism."

"That’s no better than what ISIS is doing, destroying museums and monuments," he said in an exclusive interview this week with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. "I feel very strongly about this. I think it has gone far enough. There is some idea out there that certain parts of history out there don’t matter anymore and that’s a bunch of bunk."

Fort declined to respond directly to Benton's characterization of his bill as terrorism.

“For him to degenerate into that kind of name calling is beneath a response from me,” Fort, D-Atlanta, said. “That kind of hyperbole does not allow for anything approaching a debate. It’s unfortunate that he would use that language.”

Fort defended his bill, saying the state shouldn't be in the business of formally "recognizing people who were slave owners or fought to protect slavery."

"That’s it. Beginning and end. Slavery was a crime against humanity," he said.

If someone wants to privately honor the Confederacy with their own memorial or flags, that's fine, he said. "But I don’t believe that taxpayer funds should be used to commemorate people who stole the freedom of other human beings."

Benton, a retired middle school history teacher, equates Confederate leaders with the American revolutionaries of the 18th century -- fighting a tyrannical government for political independence.

"The war was not fought over slavery," he said. Those who disagree "can believe what they want to," he said.

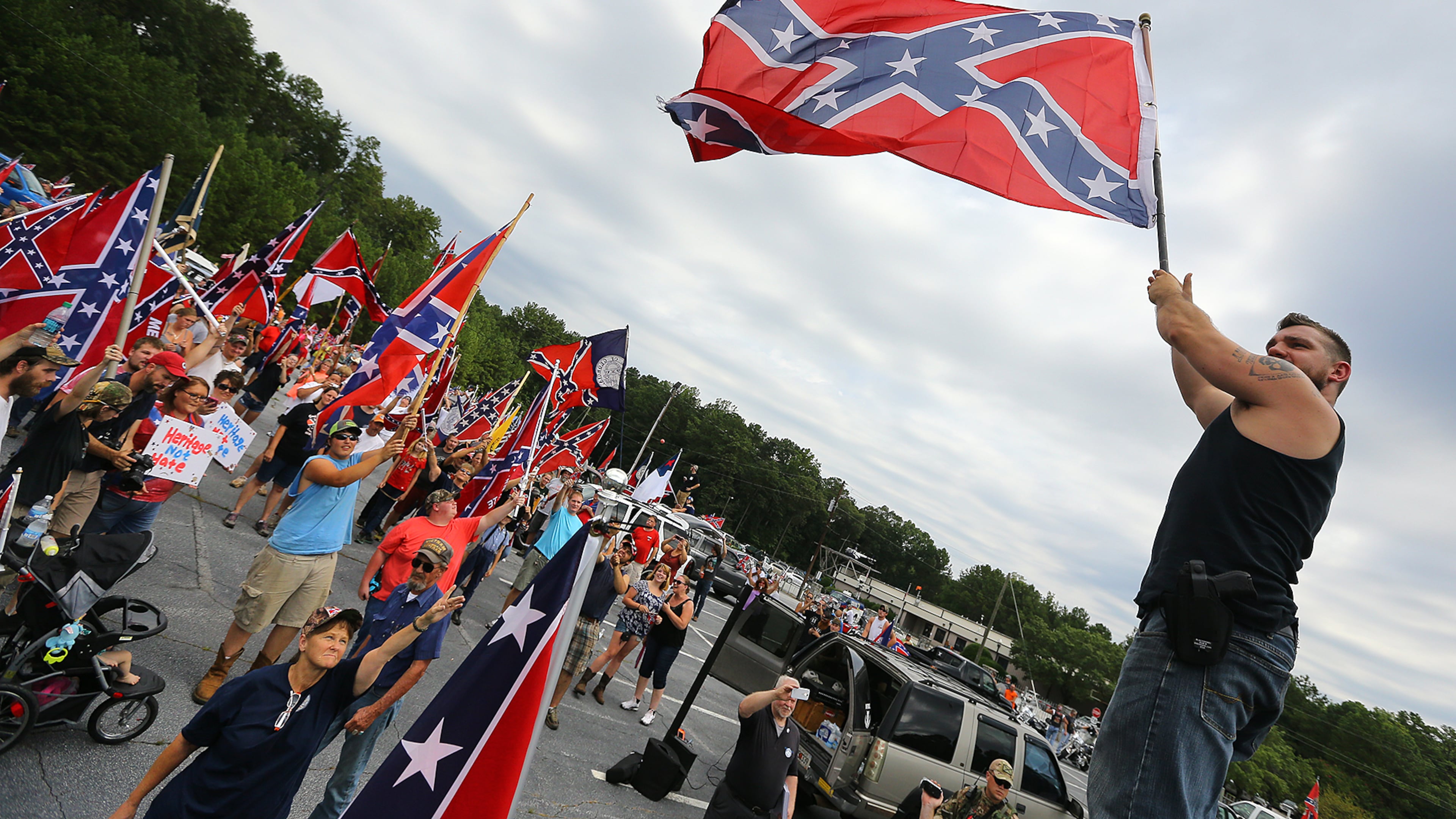

The debate over Confederate symbols is rooted more in present-day concerns, sparked by last summer's mass shooting of African-American members of a church in Charleston, S.C., by avowed white supremacist Dylann Roof. Roof posted pictures of himself with Confederate flags on social media prior to the shootings, helping to reignite a debate over the public display of such symbols.

In an interview last summer with the AJC, Benton said he saw the concern over the flag as a distraction from problems within the black community.

“That flag didn’t’ shoot anybody and when I was growing up I had a couple of those flags. In fact I still have a couple of them. It doesn’t make me a racist,” he said. “Nobody said anything about black-on-black crime, and that’s about 98 percent of it. Nobody said anything about family life and who's in the home and who's not in the home. It’s always something else that is the problem."

Stone Mountain's iconic carving has been a target since the Charleston shootings, with the Atlanta chapter of the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference both calling for it to be removed. Opponents of the carving cite the fact that the mountain was the site of the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915 and the Klan held cross burnings at the mountain for decades.

Benton said there are two sides to that story as well. The Klan "was not so much a racist thing but a vigilante thing to keep law and order,” he said.

“It made a lot of people straighten up," he said. "I’m not saying what they did was right. It’s just the way things were.”

He also said that Klan membership shouldn't be an automatic reason to dispense with a historical figure.

“A great majority of prominent men in the South were members of the Klan," he said. "Should that affect their reputation to the extent that everything else good that they did was forgotten.”

Benton said Wednesday he stands by those statements. Fort, a history professor, called Benton's comments "unconscionable."

“What he’s doing is acting as an apologist for the Ku Klux Klan," he said. “He’s right about elites like (past governors) of the state of Georgia being in the Klan, but just because it was the elites with the bullwhip doesn’t make it right.”

Benton has another bill, House Bill 854, which would require streets named in honor of veterans that have been renamed since 1968 revert back to their original names. That bill has no cosponsors and -- for both political and practical reasons -- is unlikely to get a hearing, but were it to pass it would result in a portion of Martin Luther King Boulevard revert back to its original name, Gordon Road.

Gordon Road was named in honor of Gen. John B. Gordon, a highly decorated Confederate officer who later was governor and and a U.S. senator from Georgia and was an early leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia. A statue of Gordon, in Confederate uniform and astride his horse, occupies a prominent place on the Capitol grounds.

King is not mentioned in the text of the bill, but the civil rights leader was assassinated in 1968.

More Stories

The Latest