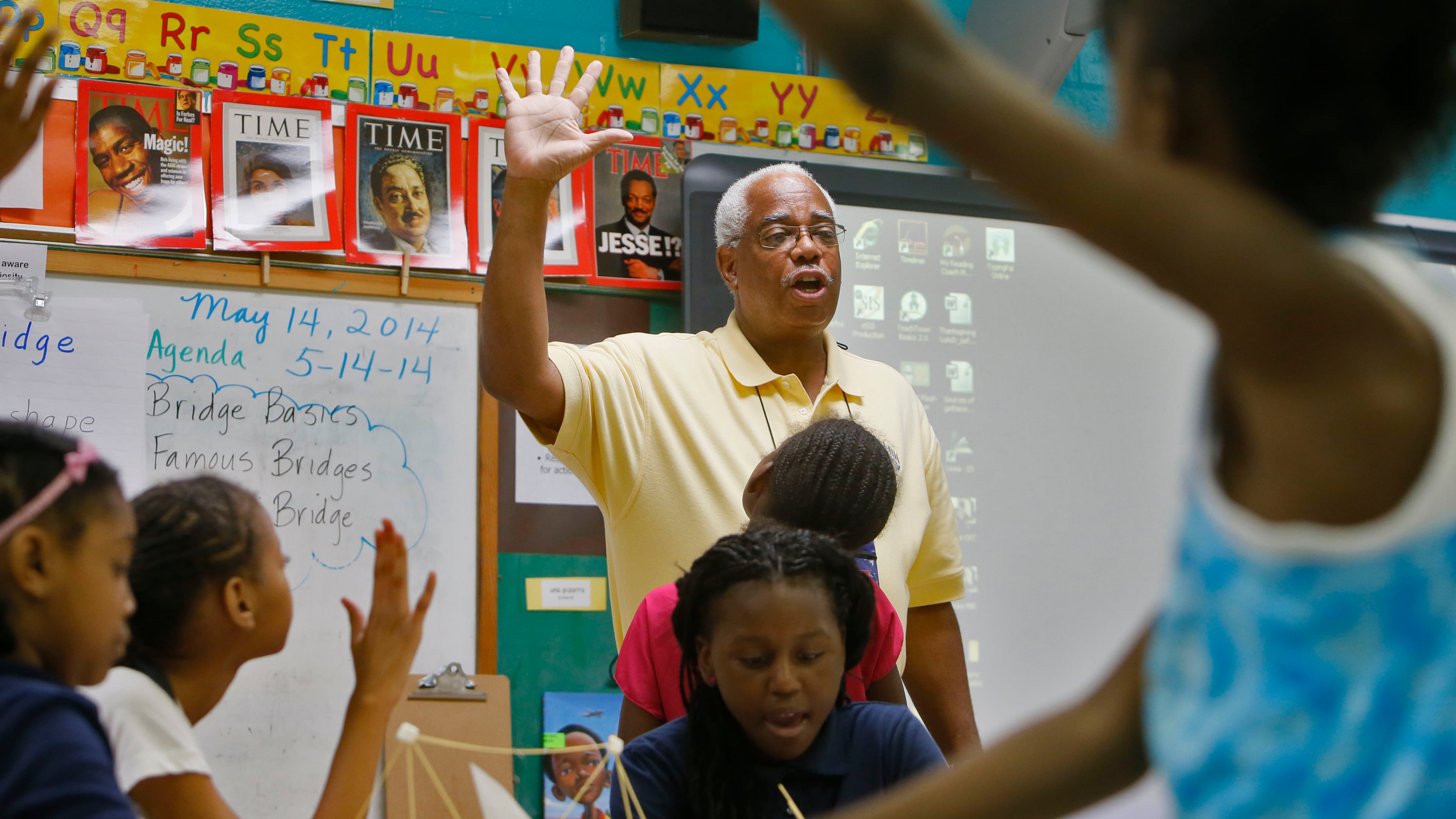

‘You can’t be what you can’t see.’ Black teachers benefit black kids

Earlier this week, I shared this Marian Wright Edelman quote: "You can't be what you can't see." That may explain why another study finds black students benefit from having black teachers.

A Johns Hopkins working paper found that if a black student has one or two black teachers in elementary school, the student is far more likely to enroll in college. One black teacher by third grade, black students are 13 percent more likely to enroll in college, two black teachers and the students are 32 percent more likely, according to the findings.

But the authors of the paper circulated today by the National Bureau of Economic Research cite several caveats with campaigns to increase the number of black teachers in front of students: Diversifying the teaching ranks so every black student could have at least one black teacher requires doubling the number of black teachers. That would entail 8 percent of all black college graduates becoming teachers rather than lawyers, IT professionals or bankers. While that may seem an admirable goal, the researchers note, in view of the salaries in education, routing that many black grads into teaching would cut about a billion dollars from the already low cumulative black income.

The researchers conclude:

“…it is likely that, for the foreseeable future, most teachers of black students will be white females. An important question is thus whether the lessons we learn here help us to harness the power of black teachers given the teaching workforce we have. Evidence on role model effects and, broadly, the idea that a single black teacher can have a large impact on a student’s educational pathways, is helpful. It suggests that scarce black teachers could be creatively allocated to face more black students. It also opens up the possibility that black teachers and other black professionals can serve as role models without teaching students for a full year, but could work through more limited exposure: for example, a recent experiment finds that one-off, one-hour visits from female scientists in high-school science classes increases the likelihood that female students apply to selective science majors in college. Another possibility is to reduce implicit bias and otherwise train white teachers to embrace a culturally relevant pedagogy, growth mindsets, and a culture of high expectations for all students. ”

In a release on the study, Johns Hopkins said:

Relatedly, another working paper by the same team titled Teacher Expectations Matter, also published today by NBER, found teachers' beliefs about a student's college potential can become self-fulfilling prophecies. Every 20 percent increase in a teacher's expectations raised the actual chance of finishing college for white students by about 6 percent and 10 percent for black students. However, because black students had the strongest endorsements from black teachers, and black teachers are scarce, they have less chance to reap the benefit of high expectations than their white peers.

Both papers underscore mounting evidence that same race teachers benefit students and demonstrate that for black students in particular, positive outcomes sparked by the so-called role model effect can last into adulthood and potentially shrink the educational attainment gap.

"The role model effect seems to show that having one teacher of the same race is enough to give a student the ambition to achieve, for example, to take a college entrance exam," said co-author Nicholas Papageorge, the Broadus Mitchell Assistant Professor of Economics at Johns Hopkins. "But if going to college is the goal, having two teachers of the same race helps even more."

The paper, titled "The Long-Run Impacts of Same-Race Teachers," appears to be the first to document the role model effect's long-term reach. The researchers previously found that having at least one black teacher in elementary school reduced their probability of dropping out by 29 percent for low-income black students – and 39 percent for very low-income black boys.

The latest findings are based on data from the Tennessee STAR class size reduction experiment that started in 1986 and randomly assigned disadvantaged kindergarten students to varied sized classrooms.

Researchers found that black students who'd had a black teacher in kindergarten were as much as 18 percent more likely than their peers to enroll in college. Getting a black teacher in their first STAR year, any year up to third grade, increased a black student's likelihood of enrolling in college by 13 percent.

Black children who had two black teachers during the program were 32 percent more likely to go to college than their peers who didn't have black teachers at all.

Additionally, students who had at least one black teacher in grades K-3 were about 10 percent more likely to be described by their 4th grade teachers as "persistent" or kids who "made an effort" and "tried to finish difficult work," the researchers found. These students were also marginally more likely to ask questions and talk about school subjects out of class.

Although enrolling in college effect is a positive outcome, one concern, according to the researchers, is that the main enrollment effect is driven by students choosing community college, where degrees aren't as lucrative as those from four-year colleges. It's also unclear because of incomplete data how many of students from the study who enrolled in college eventually graduated.

The researchers replicated the findings with similar data for North Carolina students.

"That we find similar patterns in two states — that black students, especially boys, exposed to even one black teacher in elementary school are significantly more likely to graduate high school and aspire to college —highlights the pervasiveness of both the underrepresentation of teachers of color and of the importance of role models," said co-author Seth Gershenson, an associate professor of public administration and policy at American University.

Regarding teacher expectations, Papageorge and Gershenson previously found that when evaluating the same black student, white teachers expected significantly less academic success than black teachers. Now the researchers show compelling evidence that these biases affect whether students make it to college, graduate and begin their adult life focused on a career.

The findings on expectations are based on data from the Educational Longitudinal Study of 2002, an ongoing study following 8,400 10th grade public school students that asked two teachers who each taught a particular student in either math or reading to predict how far that one student would go in school.

All teachers are overly optimistic about the college potential for all students, but the researchers found white teachers are systematically less optimistic about black students, which creates a self-fulfilling prophecy that keeps black children from considering college and perpetuates racial achievement gaps.

Higher teacher expectations from 10th grade teachers led to a 5 percent better chance of being employed, a 7 percent drop in students using the social safety net as adults, and a lower chance of students getting married and having children 10 years removed from an on-time high school graduation, suggesting these young adults are postponing starting a family in order to focus on their education and career.

"Both studies underscore the importance of gaps in information, expectations and thus aspirations," Papageorge said. "Many black students from low-income families encounter few college graduates who look like them. They may conclude college isn't something to strive for. Black teachers can counteract that view, acting as role models that provide a clear example that black students can go to college."