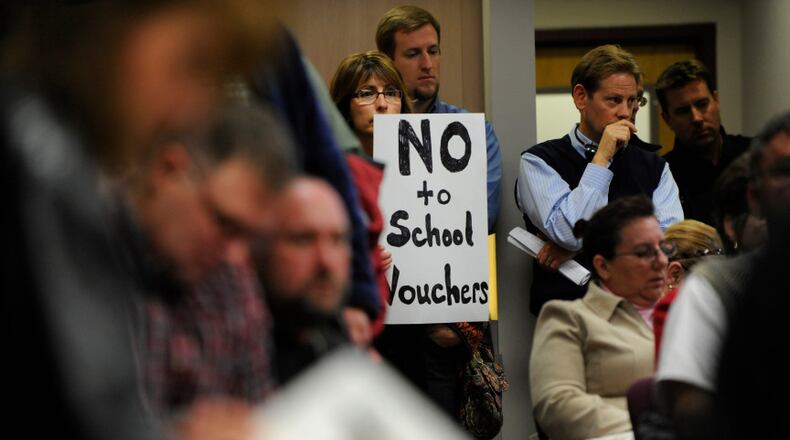

A new wave of Republican legislators in the General Assembly is falling back on an old excuse to defend a new call for school vouchers: They are duty-bound by their conscience to offer parents options.

How come they don’t feel bound to fulfill the key duty demanded of them by the Georgia constitution – provide an adequate education to the more than nine out of 10 children attending our public schools?

While the 2018 state budget increased education funding, Georgia ranks 38th in spending per student and invests $1,965 less per student than the national average. Since 2003, schools endured a cumulative cut of more than $9.2 billion.

Yet, Senate Bill 173, which would divert millions of dollars to private schools without any accountability, sprang back to life last week after it failed earlier this month.

Sponsor Sen. Greg Dolezal, R-Cumming, performed a Frankenstein-like operation and grafted the language of his defeated legislation onto House Bill 68, an unrelated education bill that survived the crossover deadline and is still viable.

Dolezal is a freshman legislator, and his legislation, packaged as an education savings accounts bill since the v-word doesn’t poll well, reflects the mistaken belief that education dollars belong to the parent.

Under that rationale, parents should be able to direct those tax dollars -- $5,500 a year on average -- toward a private school, books, tutoring or therapy, according to Dolezal’s bill.

The reality is few Georgians pay anywhere near enough in taxes to cover the cost of a child’s schooling for a year. The tax dollars that Dolezal deems the parents’ money represent the collective pooling of all the community's resources, including taxpayers without children.

The resurrected legislation -- which now has a lower cap on the number of students who could use the vouchers -- passed the Senate Education and Youth Committee Wednesday and may reach the Senate floor this week.

It has the backing of Gov. Brian Kemp and other newly elected GOP leaders who seem dismissive of the value of public education.

In endorsing vouchers, Georgia lawmakers point to Indiana and Louisiana, even though neither state has seen any academic leaps from sweeping privatization efforts.

(For another view on this issue, click here.)

It’s unclear why lawmakers cite states with debatable results when Massachusetts offers an unambiguous record of success. It’s the nation’s highest performing state, and, like almost all the countries that outperform the United States, Massachusetts excels by concentrating on improving teaching and curriculum, not by offering vouchers.

Stephen Owens, a former research and data analyst for the Georgia Department of Education and now with the Georgia Budget & Policy Institute, told the Senate Ed committee, "Even at the lowered cap, this is a huge investment in a program shown to fail in other states across the nation. In Indiana, Washington, D.C., and Ohio, we see scores go down once students take these vouchers in their new private schools. Arizona found, in one year, persistent fraud of these funds, upwards of $700,000 in 2018 alone. In Louisiana, we found that vouchers propped up failing private schools that have zero accountability compared to their public school counterparts."

The Arizona Republic reported that almost none of misspent educational savings account or ESA funds were ever recovered. There has been a lot of finger pointing with lawmakers blaming state agencies for lax oversight and agencies blaming insufficient funding to properly monitor how parents use the tax dollars.

Among the misuses of the Arizona tax dollars by parents reported by the newspaper:

The Auditor General found some parents used the ESA cards for transactions at beauty supply retailers, sports apparel shops and computer technical support providers. Auditors also found repeated attempts by some parents to withdraw cash from the cards, which is not allowed and can result in getting kicked off the program.

The audit also concluded education officials did not properly monitor parents' spending, even after questionable purchases were denied, including on music albums deemed noneducational, Blu-ray movies, cosmetics and a transaction at a seasonal haunted house.

Some parents pocketed the ESA money and sent their children to public schools. Others bought materials using their state-issued debit cards and then immediately returned them and put the refunded money on gift cards.

In 2014, a payment to a health clinic led education officials to believe ESA money had been spent on an abortion.

"Any voucher program should include accountability measures, including financial and policy transparency, performance evaluation measures and consequences for poor performance. As I look at this, I don't really see that," said Angela Palm, director of policy and legislative services for the Georgia School Boards Association.

Until recently the chair of the Senate Education and Youth Committee, Sen. Lindsey Tippins, R-Marietta, told his less experienced colleagues, "In 20 years of being involved in the public policy arena for education, one thing has always been consistent, that is the public's concern over accountability, both financial or academic. I don't believe this bill lends itself to either. And, I think in that case, it is very, very deficient."

He’s right.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured