A University of Georgia education professor today responds to a recent interview I did with Stanford economist Eric Hanushek about his new study on the achievement gap.

Peter Smagorinsky, a frequent contributor to the AJC Get Schooled blog, challenges Hanushek's comments on the role that teacher quality plays in student performance. He believes Hanushek underplays the effects of poverty on student performance.

By Peter Smagorinsky

Get Schooled recently ran an essay titled "New study: Achievement gap persistent and resistant to reform." The story summarized economist Eric Hanushek's dismal view of what is called the "achievement gap between low and high income students in the United States."

The study relies on four sets of standardized test scores over a 50-year timespan, concluding that “A stark opportunity gap persists between America’s haves and have-nots, despite a nearly half century of state and federal attempts to provide poor children with extra resources to catch up. Yet, the gap hasn’t budged.”

To Hanushek, whose thinking is typical of policymakers, tests tell everything we need to know about teaching and learning, and by extension teacher education. Hanushek has a villain or two to account for the differences between the test scores produced by students from the lowest and highest SES levels: “a lack of meaningful reinvention of high school,” and “a decline in teacher quality,” which to Hanushek and colleagues “fell as women gained access to career opportunities outside of the classroom…We are shirking the issue of teaching quality. …There is no direct effort on a national scale to enhance the quality of the teaching profession.”

Hanushek concludes, “Scores in these achievement tests are actually good measures of expected future incomes, so, if kids are unprepared for life, or at least for jobs and college, as seen by these test scores, they are going to have their own families of poor kids. That is the tragedy.”

What I find tragic is the specious logic that drives this argument.

Poor kids, according to this reasoning, don’t perform nearly as well as wealthy kids on standardized tests. Standardized tests predict future outcomes, which makes improving test scores the primary purpose of education in order to close gaps in affluence. Because the test scores continue to produce gaps, teachers are doing a poor job of preparing students for their futures, and teacher educators are to blame for not preparing teachers to teach poor kids to do better on standardized tests. Teachers and teacher educators are thus responsible for poverty.

That is some bizarre thinking.

I would interpret the problem quite differently. Poor kids live lives of uncertainty. They may move frequently, eat less nutritious and regular meals than affluent kids, have insufficient access to health care, have difficulties with transportation, attend schools that are unsanitary and decrepit, lack clean clothing that fits, and face innumerable other challenges. These conditions are associated with struggles to succeed in school and are a consequence of social policies that are designed to keep poor people in poverty.

Growing up poor predicts an adulthood of poor health, unstable emotional life, low income, and other challenges. These general, cross-population statistics elide the problem of racism in discouraging and preventing people of color from having access to opportunities to change their economic and health-oriented prospects in life.

In other words, if low-income children end up being low-income adults, it's not because teacher education programs are producing a second-rate teaching force that has been diluted by opportunities to earn more money in careers outside education. It's not because these teachers are doing a poor job with test preparation. It's because historically, in nations like the United States that promote personal selfishness over national solidarity, the Matthew Effect has prevailed: The rich get richer, and the poor get poorer.

It has nothing to do with standardized test scores. It has everything to do with how society is structured. I have taught in wealthy communities outside Chicago, where everyone went to college. The kids were well-fed, had access to health care, had tutors when they needed them for both regular classes and standardized tests, got cars when they turned 16 (and not the little compact models driven by teachers), attended school in well-maintained facilities, didn’t need to work after school, and had countless other privileges and advantages.

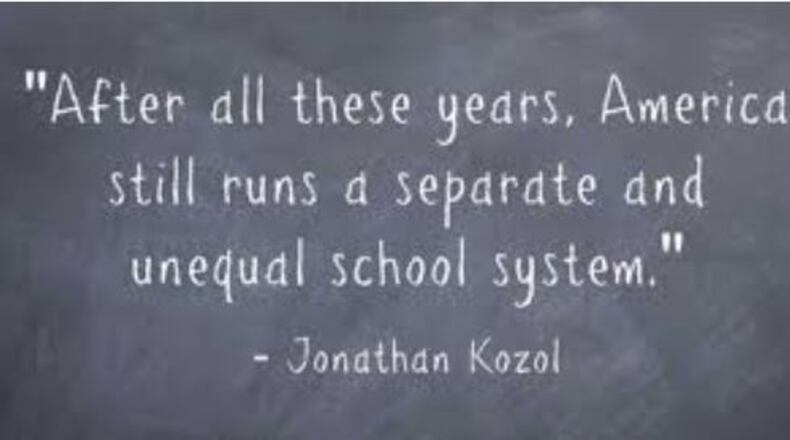

I've also spent a few years as a substitute teacher in Trenton, N.J., and Chicago. The condition of school buildings in Trenton has been well-documented as dangerously unsanitary. Atlanta's schools aren't much different in many cases. In many ways, schools today are not much different from those studied by Jonathan Kozol in "Savage Inequalities" several decades ago, with affluent people giving advantages to their children and poor people stuck with the worst living and educational conditions imaginable. And the poor still have trouble escaping poverty, for the same reasons.

Yet to Hanushek, the problem is that weak teachers aren’t preparing kids—who may not know where they’ll sleep that night—for standardized tests. That, and not intergenerational poverty within the confines of an inequitable society, is the problem.

Perhaps Hanushek should look at the sorts of economic policies promoted at the Hoover Institute, where he is a Paul and Jean Hanna Senior Fellow, to explain why poor people have trouble escaping poverty. Neoliberal economics are devoid of compassion, reducing everything to economic impact and numeric indicators. It’s much easier to box people into limited lives and then blame them for not being able to climb out than it is to walk a mile in their worn-out shoes and understand the obstacles they face to reaching a happy destination.

No, that’s too hard. It’s much easier to say that test scores, which are associated with wealth disparities, are actually causes of problems rather than symptoms of deeper problems. But simplistic thinking like Hanushek’s is what informs policy. Everything else is too complicated. And people wonder why these problems are so persistent, and their solutions so elusive.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured