Humanities classes can rewrite life script of incarcerated Georgians

This is a remarkable essay by Dr. Sarah Higinbotham about a recent philosophy class at an Atlanta prison. She discusses the power of literature, writing, history, art, and philosophy to electrify and engage students, regardless of the setting.

Higinbotham teaches Shakespeare and early modern literature at Oxford College of Emory University. She writes about the violence of the law in early modern England and human rights in literature.

Along with Bill Taft, she co-founded and co-directs a nonprofit called Common Good Atlanta that has connected Georgia's colleges with Georgia's prisons since 2008.

By Sarah Higinbotham

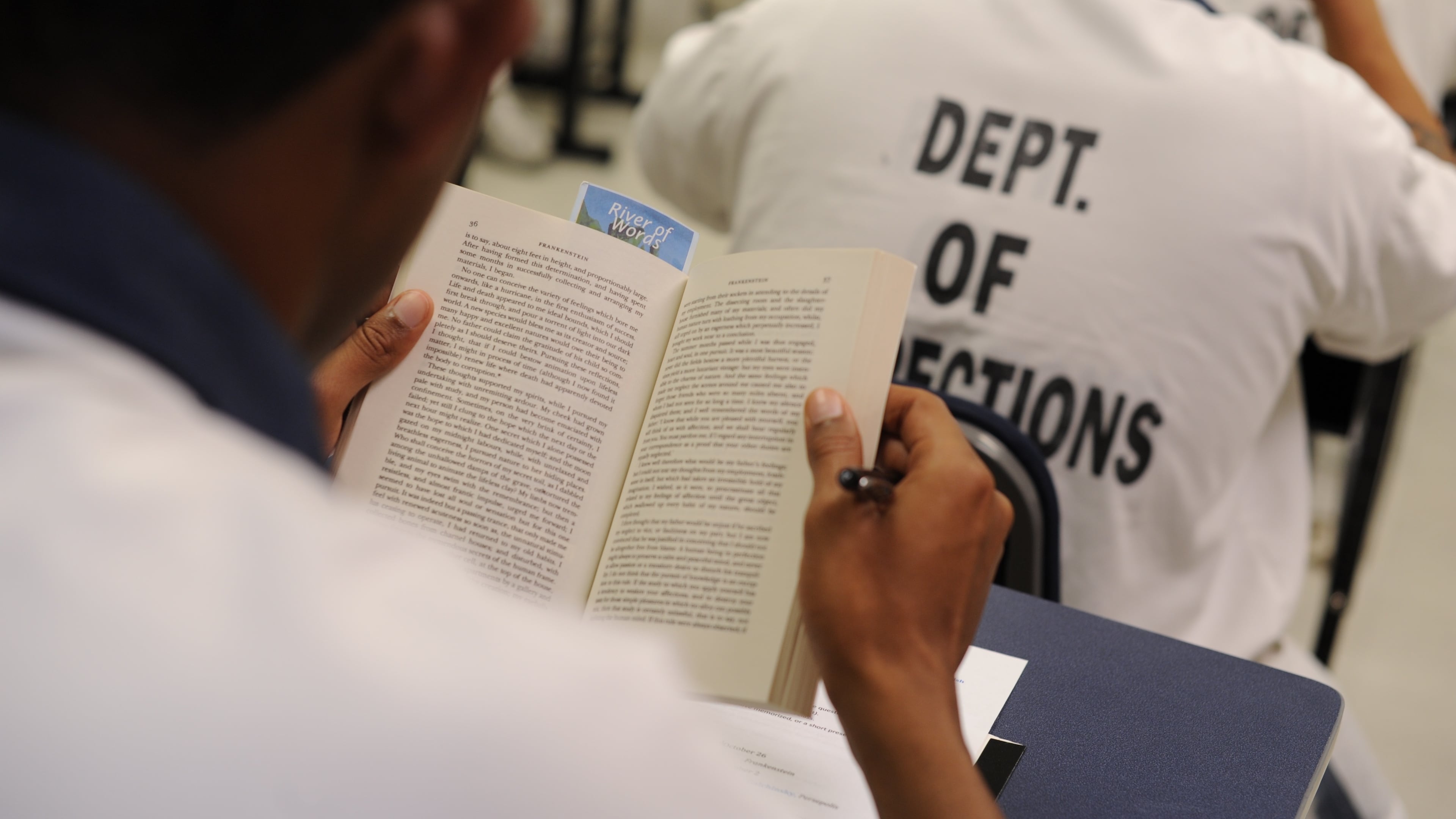

Last night I joined a philosophy course taught at an Atlanta prison. The 19 men had already studied Greek stoicism – they cited Epictetus when discussing universal ethical standards – but on the evening I visited, they were examining Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics. What does it mean to be part of a community? What makes a life worthy? What does it mean to be ethical, to be responsive to others, to be oriented toward the good?

These are questions that Aristotle, the scholars at Metro Reentry Facility, and their professor John Lysaker asked of each other. Each man had Aristotle's Ethics open in front of him, heavily annotated and underlined in anticipation of the discussion. I didn't have a book, and when one of the men behind me noticed, he moved next to me in order to share his copy:

“Every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action as well as choice, is held to aim at some good.” Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book 1

For two hours, the men and their professor engaged in a relentless dialectic. Their inquiry of each other, of the text, and of “the good” ranged from relativism, to wisdom, to samsara, to capabilities theory. But the through-line was eudaimonia -- happiness, or human flourishing, or blessedness – a concept instantiated in that very prison classroom on a hot July evening.

When Dr. Lysaker paused to ask the time, and someone answered “7:15,” the animated discussion turned to a low chorus of frustration and even grief. Class was almost over, and it was too soon.

The two-hour discussion of abstract philosophy challenged me at many points. I couldn’t quite distinguish whether an instrumental good undermines an inherent good, where Epictetus contradicts Aristotle, or the distinction between moralität and sittlichkeit. After class, as we stood talking in small groups, I laughed with the incarcerated students about my attempt to keep up with them intellectually, and pointed out that when I am teaching them Shakespeare, we are discussing books that have a narrative: “where’s the plot in Aristotle?” I asked, “I think I need plot.”

Instantly one of the guys gestured expansively at John Lysaker and around to his fellow students and himself, replying with a smile, “He’s the plot, and we are the plot.”

In his answer, I heard an education unfold. And I was struck by the good, the "eudaimonia," that the humanities instill in people. In the case of the college students at Metro Reentry Facility — studying literature, writing, history, art, and philosophy through the Clemente Course in the Humanities — they grow to see themselves as agents of their own narratives.

Rather than having plots written onto them by the media, by tough-on-crime politicians, by structural injustices, or by virtue of their criminal convictions, they can see themselves emerging from prison as someone other than a felon. Studying Shakespeare, American rhetoric, the Federalist Papers, Renaissance art, and classical philosophy allows them to acknowledge their human failures without reducing themselves to those failures.

More broadly, the humanities equip us all to see that we are our own narrators and that we can orient our stories toward good. We can seek friendships in which we debate and enact what that good entails. We can form communities in which that good flourishes amid trust, forgiveness, and imagination. Those of us who are privileged to teach the humanities – both outside prisons and within – witness these transformations in our students, and ideally, in ourselves.

The U.S. Department of Justice widely documents that people who have access to education while in prison are up to 43% less likely to commit another crime after they are released. The same study documents that every dollar spent on prison education saves up to five dollars in re-incarceration costs. Empirically, college in prison "works." But the inherent good of college inside prisons manifests itself in the kinds of dialectic conversations that I heard last night -- less measurable than recidivism data, but no less consequential. The people we are teaching inside prisons are mastering the skills of reasoning, listening, writing, and speaking with each other, which are essential skills for meaningful participation in the democratic society they will soon rejoin.

The courses at Metro are part of an all-volunteer program called Common Good Atlanta directed by Bill Taft and me. For the last 11 years, professors like John Lysaker travel to four men's and women's state prisons, go through security, and teach rigorous college courses to incarcerated people. They donate their time, cover their own transportation costs, and sometimes even pay for the books. Men and women incarcerated in Georgia can earn college credits from Bard College and Georgia State University, privately funded by the nonprofit Common Good Atlanta and facilitated by a successful collaboration with the Georgia Department of Corrections. The courses are taught by professors from Emory, Georgia Tech, Georgia State, the University of Georgia, Kennesaw State, Morehouse, and Spelman.

Our students – when soon released from prison — will return to Atlanta to continue writing their own stories, plots that can both reflect and shape their inherent human dignity.