Does implicit bias begin in preschool? Yes, says new study.

A new study out of the Yale Child Study Center within the Yale School of Medicine reveals the role of "implicit bias" in how teachers view preschoolers. Race of teachers and students play a role but in ways that may surprise you.

"Implicit bias is like the wind. You can’t see it but you can sure see its effect. It does not begin with black men and police; it begins with preschool," said Walter S. Gilliam, director of the Edward Zigler Center in Child Development and Social Policy and associate professor of child psychiatry and psychology at the Yale Child Study Center, in a press call with reporters Monday

A leader in the field whose work on preschool expulsions is widely cited, Gilliam said preschool is the best early frontline defense against the negative impacts of implicit bias.

"What is disturbing to us is our early childhood settings are not immune to the same racial disparities that plague our K-12 settings," said Linda Smith, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Early Childhood Development, Administration for Children and Families, Dept. of Health and Human Services, in the media call.

Here is the official release:

A first-of-its-kind research study has found that preschool teachers and staff show signs of implicit bias in administering discipline, but the race of the teacher plays a big role in the outcome.

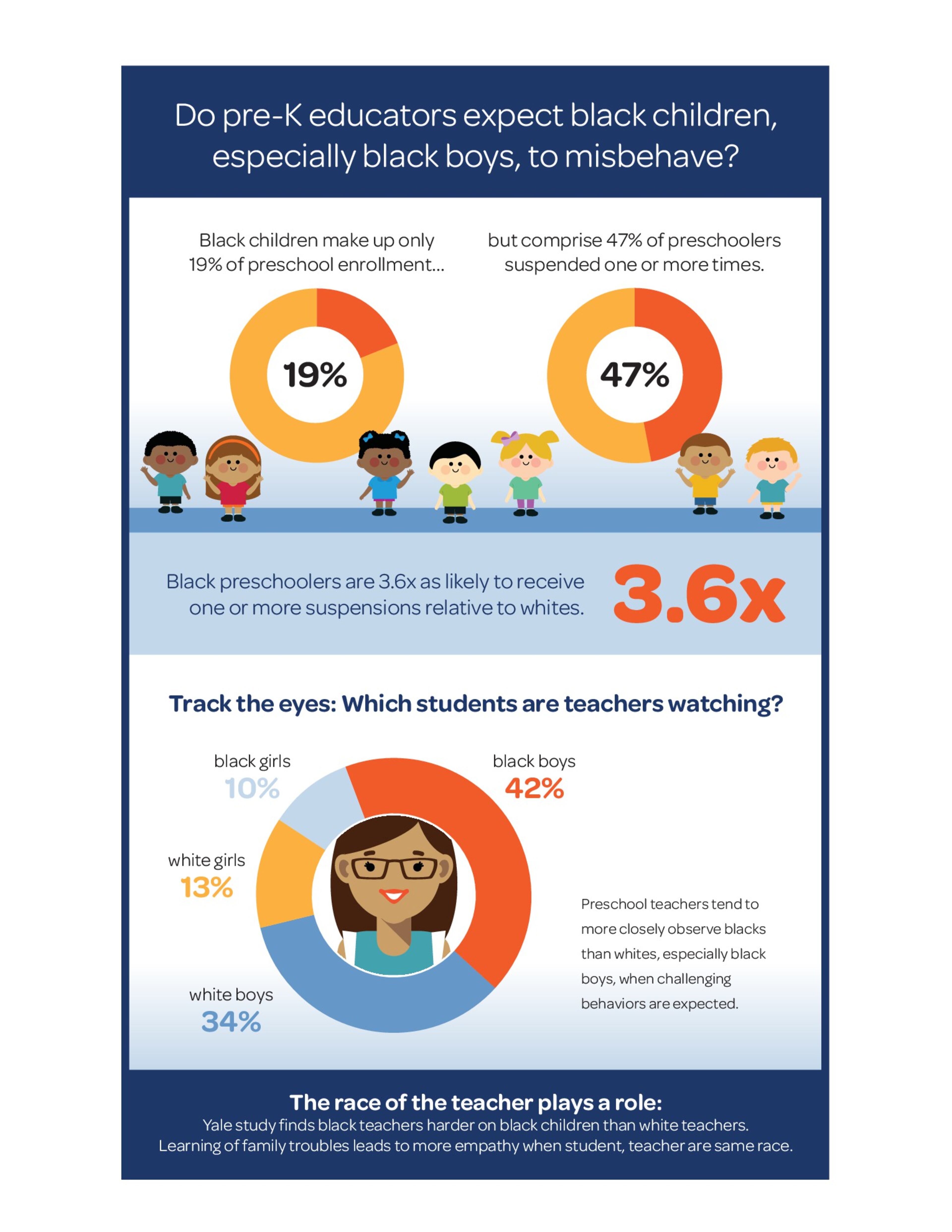

The research, by the Yale Child Study Center within the Yale School of Medicine, used sophisticated eye-tracking technology and found that preschool teachers "show a tendency to more closely observe blacks and especially black boys when challenging behaviors are expected."

But at the same time, black teachers hold black students to a higher standard of behavior than do their white counterparts, the researchers found. While the study did not explore why this difference in attitude exists, the researchers speculated that black educators may be demonstrating "a belief that black children require harsh assessment and discipline to prepare them for a harsh world."

White educators, by contrast, may be acting on a stereotype that black preschoolers are more likely to misbehave in the first place, so they judge them against a different, more lenient standard than what they're applying to white children.

Discipline data collected from the nation's public schools shows that black and Latino students are suspended and expelled at much higher rates than white students "so we set out to examine whether implicit biases in early education staff may be a contributory factor," observed Dr. Walter S. Gilliam, Director of The Edward Zigler Center in Child Development and Social Policy and Associate Professor of Child Psychiatry and Psychology at the Yale Child Study Center.

"The tendency to base classroom observation on the gender and race of the child may explain in part why those children are more frequently identified as misbehaving and hence why there is a racial disparity in discipline," added Gilliam, one of five researchers who conducted what is thought to be the first such study of its type.

The Yale researchers noted prior studies have established that implicit biases are pervasive across all people and institutions of society. In the education setting, previous research has established that expulsions and suspensions often are based on adult decisions rather than actual child behaviors, raising questions about whether the adult teachers and staff come to the classroom with an implicit bias about boys and children of color.

The new research, conducted in 2015, applied a sophisticated methodology that included eye-tracking of 132 early childhood staff, most of whom were classroom teachers. On average, the study participants had 11 years of professional experience.

The two-part study included a session watching videos of classroom behavior while eye-tracking equipment determined which children they were observing, with the educators being told only that the researchers were interested in learning how quickly and accurately the teachers could detect challenging behavior. They then watched a total of 12 clips, each 30 seconds long, featuring a black boy, black girl, white boy and white girl. No challenging behavior actually was depicted in the videos.

In the second part of the research, educators read different vignettes detailing instances of misbehavior in the classroom. The researchers manipulated the race and gender of the children in each vignette by using different names for perceived black and white children, such as DeShawn versus Jake. After reading each vignette, the educators were asked to rate the severity of the misbehavior on a five-point scale and also to rate the likelihood that they would recommend suspension or expulsion.

The first part of the study showed the educators spent far more time gazing at black students compared to white students when the teachers expected challenging behaviors to occur. Black educators spent much more time gazing specifically at black boys. The vignette responses found that "white early education staff rated the severity of behavior more leniently for black children while black staff rated the severity of behavior more harshly for black children."

The report noted that white teachers appeared to be acting on a stereotype that black preschoolers as a group were more likely to engage in challenging classroom behavior, "so a vignette about a black child with challenging classroom behaviors is not appraised as being unusual or severe."

Interestingly, when teachers were told a child faced a challenging home life that might explain their behavior, the teacher responses also depended on race. When the races of the child and teacher matched, the teachers became more empathetic and rated the misbehavior less severely. But when the races differed, the teachers rated the behaviors more severe and appeared to become overwhelmed by having to factor in the home stressors and viewed the misbehavior as being more hopeless.

"We think it's pretty clear that stereotype biases may account for the differences we observed in where early educators place their attention inside the classroom," noted Gilliam. "We also know that implicit bias can be reduced through proper training and should be a core component of early childhood teacher education.

"The field of early education is based on efforts to give all children the best chance to achieve their potential," Gilliam continued. "Early educators are our nation's frontline defense against the harmful effects of implicit biases. The fact these early educators chose to participate in this study even after they were later told that we were examining their biases speaks volumes about the courage and values of these professionals, who are so under-paid and under-supported in the important work they do for our children."

The Yale research is part of a broad effort to understand why African-American and Latino students, as well as children with disabilities, are suspended or expelled at highly disproportionate rates compared to white children. The U.S. Department of Education recently reported that black children make up only 19 percent of preschool enrollment but comprise 47 percent of preschoolers suspended one or more times.

The Yale research also was undertaken at a time when local, state and federal governments are paying increased attention to the accessibility and quality of preschool classes for the very young. President Barack Obama launched the "My Brother's Keeper" initiative two years ago to address opportunity gaps facing boys of color and earlier this summer, the House Appropriations Committee recommended an increase in federal funding for Head Start and other early education programs. New York City is about to enter the second year of its "Pre-K For All" program and in Virginia, the state is supporting a Pre-School Initiative to provide early education to at-risk 4-year-olds who aren't served by Head Start.